Postmodernism is a tricky term to define. There are a host of variant definitions of the term. Postmodernism, in the work of Martin Heidegger and those who follow in his wake, denotes a positive and hopeful term for breaking away from the suffocating and dehumanizing elements of scientific modernity. For Jean Francois Lyotard, in his 1979 La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir, postmodernism captures the breakdown of the narrative structures and confidence of modernity. For Frederic Jameson, the American Marxist theorist, postmodernism is a later state of modernity in which American capitalism is the dominant global system and presents its wealth and might through architecture and culture. At the same time, for Jameson, postmodernism is defined by the desire to return to an idealized past through electronic art and culture.

Such a view is curious, for Jameson’s magnum opus Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism was published in 1991; moreover, the article on which the book was based was originally published in 1984. Here in 2024, it is humorous to see Jameson suggesting that the people of the 80s and 90s were longing for earlier and allegedly better times, just as we people of the 2010s and 2020s are longing to return to the (relatively) more stable and allegedly better times of the 1980s and 90s. At least some elements of Jameson’s thesis ring true, for, as postmodernity accelerates further, so too does the dire to escape from postmodernity into imagined pasts.

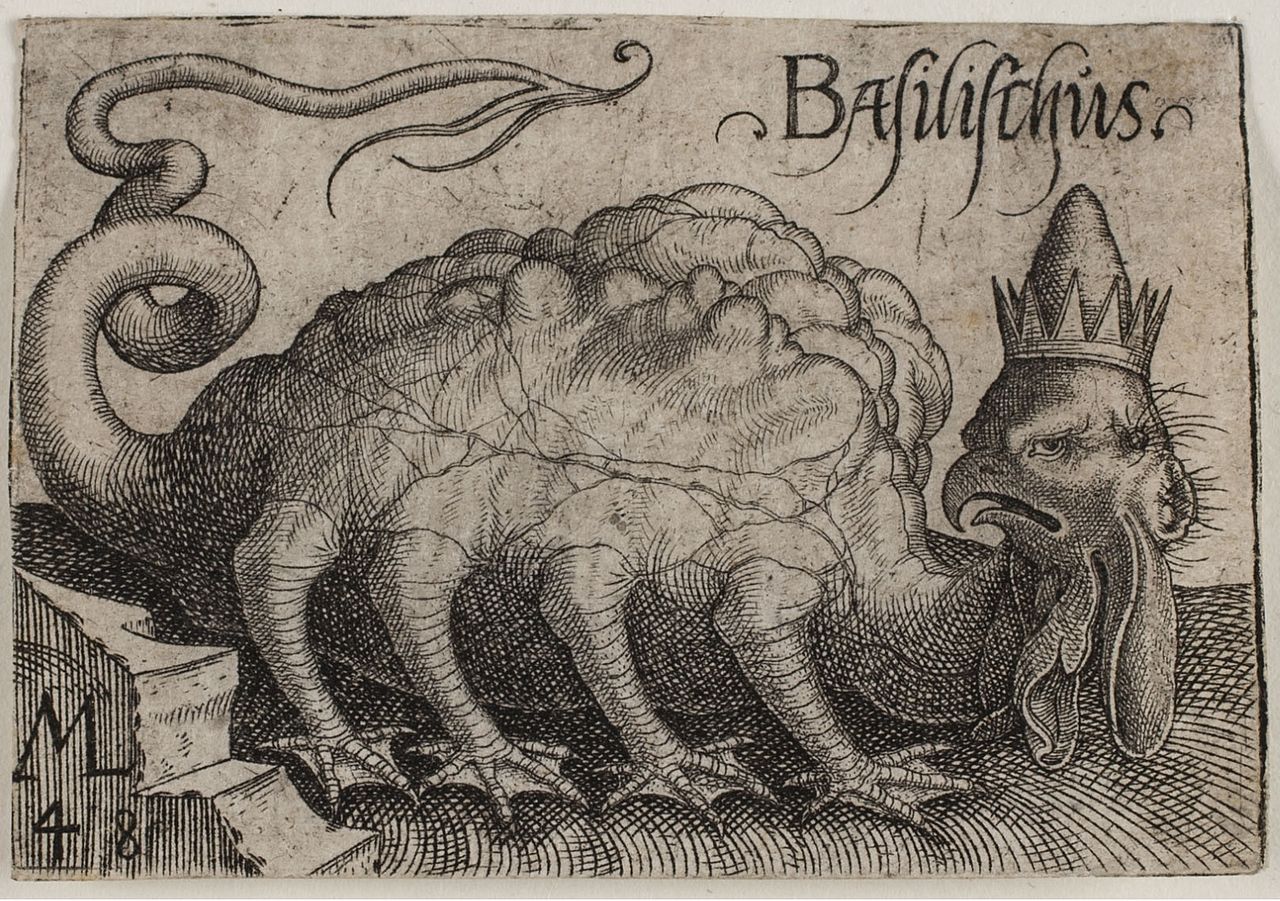

One of the most pronounced imagined pasts in which twenty-first century postmoderns travel is the Dark Age period from the fall of Rome until the emergence of the High Middles Ages. For young people—especially those on the political right, whether pagan or Christian—this time, while traditionally viewed as a low point in Western Civilization is, in fact, a high point of Viking and wider Germanic culture before it succumbed to the allegedly corrupt late medieval period. In his recent work, Basilisks and Beowulf: Monsters in the Anglo-Saxon World, Tim Flight provides a vision into the murky world of Anglo-Saxons, a people who migrated from Germany and Denmark to England.

Basilisks and Beowulf is, as the title suggests, divided into two sections. The first is a discussion of how the Anglo-Saxon peoples depicted the animals and fantastic creatures that dwelt in the wild, untamed portions of the world as guardians of the wild. The second section is a detailed and innovative (and fascinating) analysis of the medieval poem Beowulf. Flight places the Anglo-Saxon period as lasting from the fifth to the twelfth century. Such a view is somewhat controversial, as the Norman invasion occurred in 1066. Nonetheless, historians agree with Flight that the Anglo-Saxons were, in fact, a host of Germanic tribes that settled in Britain beginning in the fifth century. Flight quotes the Welsh monk Gildas who chronicled the decline of the British kings, whom Gildas called “chickens,” and the emergence of Germanic mercenaries in Britain, whom Gildas refers to as “wolves.”

Despite Gildas’s description, Flight, aligning himself with much contemporary research, argues that the Germanic conquest of Britain was undertaken through (mostly) peaceful settlement. Flight notes that the most pronounced change for the Anglo-Saxons came with arrival of St. Augustine in 597 at the behest of Pope Gregory I. The Germanic peoples of Britain eventually became Christians and the process took some time. The arrival of Christianity was accompanied by study and literacy and formation of monastic communities that themselves nurtured such important early medieval figures as Bede and Alcuin.

At the heart of the Christian Anglo-Saxon vision, according to Flight, is the vision of an ordered universe craft by God in which everything is held in its right place. At the same time, the world is marred by sin and a place of punishment for humans. In fact, Flight makes the bold statement that the Anglo-Saxons had the most harsh vision of the natural world of any early medieval people. Flight further notes that the terrain of England was harsh and hostile, dotted by forests moors, and swamps. England moreover held a variety of “super-predators” such as the wolf, the wild boar, and the Eurasian brown bear as well as, at least potentially, the Eurasian lynx.

These animals were potential dangers to humans, as is famously memorialized in the Sutton Hoo purse lid depicting a man being attacked by what appear to be wolves. This figure serves as a symbol, in Flight’s view, of the Anglo-Saxon vision of the world as a battle between humans and an often hostile nature. Flight locates one of the origins of this view as the historical “Roman” vision of Christianity as being associated with city and civilization and paganism being associated with the wild. Thus, the Anglo-Saxon world was marked by boundaries between good and evil and civilized and wild. The wild was occupied by bears, dragons, wolves, and a host of other monsters drawn from classical literature as well as various northern European traditions.

One of the greatest Anglo-Saxon heroes who is capable of traversing these boundaries is the hero Beowulf, to whom Flight dedicates the later chapters. The story of Beowulf was first recorded around A.D. 1000, but it is rooted in an earlier pagan story. Much of this material will be familiar to readers. However, Flight makes a couple of valuable points that connect Beowulf to his broader thesis on Anglo-Saxon culture. The first is Flight’s emphasis on the fundamental humanity of the poem’s villains: the Grendelkin, or, Grendel and his mother. Flight argues that the Grendelkin are fundamentally humans who have made immoral decisions and become monsters. By crossing the boundaries of morality through their hatred and violence, they become creatures of the wild, living outside of Christian civilization. There is thus a warning to the reader that he or she could become a monster through choosing to follow the wild and dark path of immorality. This first point is tied to Flight’s second, which is his notation of Beowulf’s own “wild” side. Beowulf himself, although the Christian hero, is nonetheless capable of crossing over to the wild and fighting like the wild creatures themselves. Thus, within Beowulf’s story is a repetition of the danger of being swallowed up by wildness if one is not civilized and baptized.

The problem with the past is that it is both imminently present but, at the same time, markedly lost. There is a definite difference between the life of a postmodern sitting in a comfortably heated room playing Skyrim, a video game set in a fantastic version of the Viking Era, or streaming a Netflix series such as Barbarians or Amazon Prime’s Britannia. However, as Tim Flight suggests, the past is not completely lost to us, and the fascination with fantastic beasts remains. Moreover, we have the habit of classifying these beings and even people outside of us as monstrous. However, as Flight suggests in his conclusion—and as the Anglo-Saxons themselves knew—humans must always be wary that the most dangerous monsters are those that lie within.

1 comment

D. M. Garzonio

Thanks for this insightful review, which has certainly piqued my interest in exploring this book further! Your observations regarding the political Right’s fascination with the Dark Ages are particularly thought-provoking. Indeed, the tendency to romanticize this period is often evident in far-right neo-pagan movements, wherein there’s a concerted effort to (re)shape historical narratives to fit militant and racist agendas, often with tenuous historical evidence at best.

(I’m reminded here, too, of Peter Mommsen’s recent article in Plough, which was recommended a few weeks back on FRP in the Water Dipper).

I wonder, though, if the sentiment towards romanticizing the Dark Ages, isn’t also prevalent among factions of the political and neo-pagan Left, particularly those with Anarchist leanings. Consider the context of Rome’s declining influence over its vast empire and the absence of a fully established Christendom across Europe during that time. In such a scenario, where centralized authority wanes, there’s ample room for individuals and communities to envision alternative modes of governance and societal organization.

Comments are closed.