A student of mine is starting a business to teach three-year-olds how to code. Yet apparently this is smart living in 2024. If you’re a young adult, forget starting a family and that guitar collecting dust in the corner, because there’s no time like the present to get ahead, or at least keep up, or at least not fall too far behind…

A quarter of a century ago, Wendell Berry wrote, “the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines.” That division has come, and all must choose on which side of the divide to stand.

In saying that, I assume that the freedom to choose is real. Many people, however, show little to no confidence in the reality of their own free will. It is ironic that the West has brought individualism and equality to the fore of our attention while its science tries its best to decimate the basis for any account of actual free agency. Even in an age of post-Newtonian physics, the doctrine of determinism is having its day in the sun. But the reason we doubt our free will is not just due to the influence of mechanistic science. Part of the reason so many fall for determinism and think free will is an illusion is because so many people today are slaves to their inclinations—and very few pursue “useless” things anymore. With the death of philosophy and most of the rest of the liberal arts has come the death of faith in what makes us essentially more than meat-machines, and that is a dangerous place to be. Genetic and engineering atrocities enter through the cracks of a broken anthropology; there is no essential mixing of creature and machine. As Mary Harrington writes, “You can’t have transhumanism without throwing out humanism.”

It is an obvious fact that the humanities have died out and nearly everybody now is rushing to get certified in some form or another of computer science. Students enlist ChatGPT to write their essays in response to tired professors using ChatGPT to write their lectures. Technology is changing ever faster in this age of “liquid modernity,” much faster than we humans can adapt or evolve to keep up with. To compensate we sink deeper into the quicksand of quick and easy answers, trying to keep up and hold on in an increasingly saturated market.

With the STEM departments now receiving nearly 100% of funding, contemporary trends are not especially surprising. The artes liberales are now seen as an antique relic of the past, a quaint pursuit of days gone by. Today is the day of the digital watch, the self-driving car, the virtual assistant. Children are taught to read as early as possible and sent to school to learn the skills necessary to land a well-paying job. Parents fail to look at who their child is, and pressure them into a mold ill-fitted for most. I tutor English students—most of them in their 20s and 30s—and in my hundreds of hours of conversations with dozens of them, I have come to the conclusion that most of these poor kids have no idea what life is about or what human beings are for. Their home and education environment has ensured they never had the time to give such questions a moment’s reflection. They possess few if any creative skills, lack imagination, and are usually overworked and overwhelmed.

If leisure is the basis of culture, then ours is a culture without foundation. As such, we no longer find it surprising when Robert Sapolsky or Sam Harris tell us behavior is determined and free will illusory; everyone does exactly what you’d expect, all the time. We work too much, sleep too little, and waste whatever is left of our time being passively shaped and defiled by TikTok, Netflix, and Pornhub. And because we behave so predictably, it indeed appears that we are slaves to our impulses, with nothing of significance separating man and beast at the level of the rational will. Delayed gratification, when it occasionally gets exercised, is usually endured for the sake of some other form of passive entertainment (an all-inclusive vacation perhaps) but certainly not because the virtue is valued, and even some animals do as much. Everything that is actively pursued is done for the sake of something else—hence no pursuit is liberated to be enjoyed for itself. Such a culture inevitably crumbles.

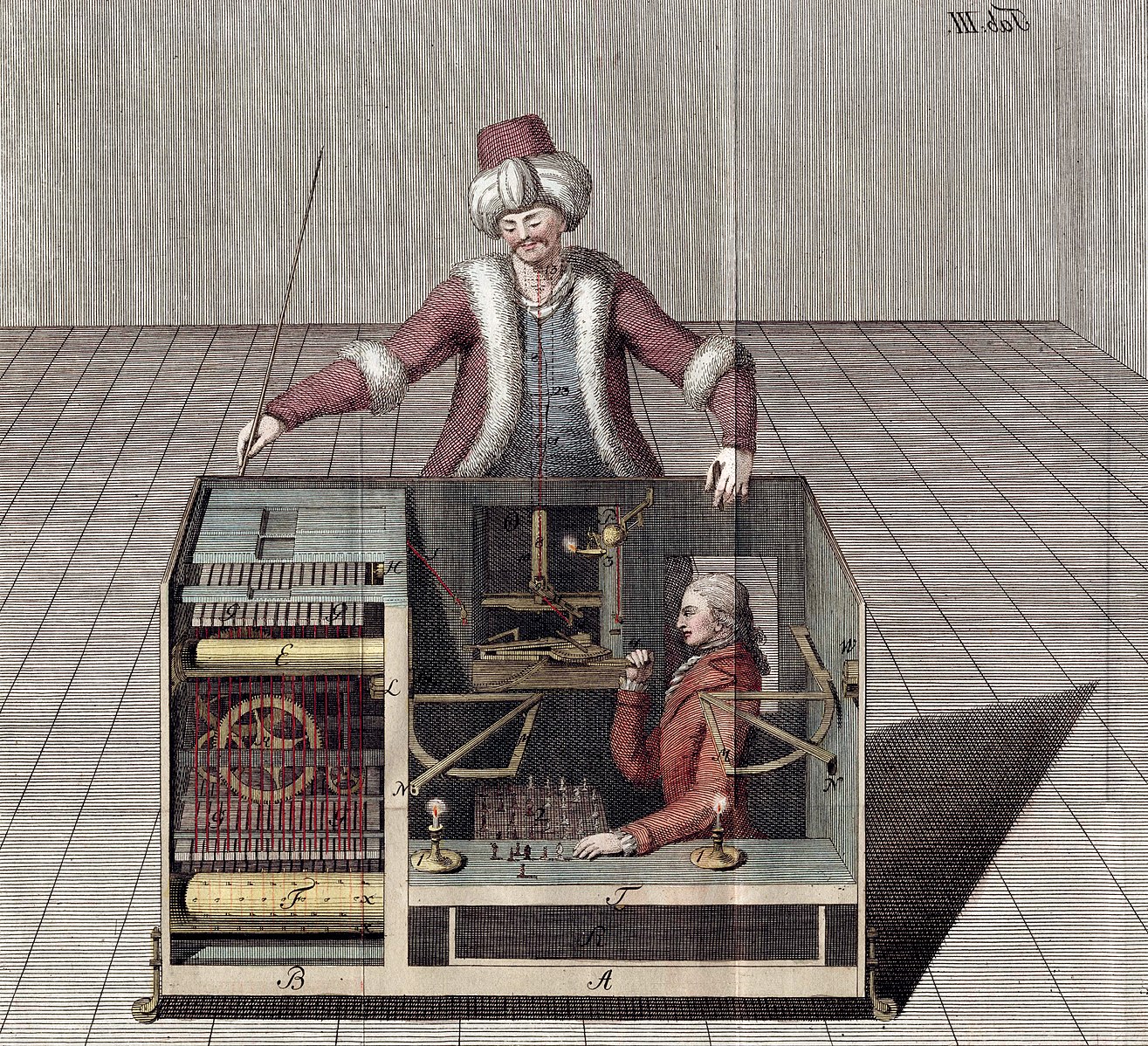

There is, according to Philip Goff, a consensus among Anglophone philosophers about something, and it is this: on the subject of free will, most (about 60%) are compatibilists, meaning they are determinists who believe freedom consists in the ability to follow one’s desires. They thus manage to have their deterministic cake and eat it too, in effect reducing the definition of freedom to the uninhibited pursuit of desire. The lack of belief in actual free will ought to cause more concern than it does, since with a loss of free will comes a corresponding loss of moral responsibility—if nothing can be done about one’s behavior, then one cannot be held truly responsible for anything. Like a self-playing piano, deterministic man is a fool to think he could play another tune and defy his programming. Such theories—popular as they are—are unconvincing, since they presuppose what they purport to prove, namely that impulse alone determines action; many neuroscientists seem to think that if they can trace impulses back to a primary sequence of them, then it follows that free will was illusory all along. That does not follow however—for some reason, many very intelligent thinkers go through life without making the crucial distinction between correlation and causality.

As I was saying, no free will = no moral responsibility. Alas, responsibility is another thing lacking in our age, and this point actually does seem to be getting some attention. However, amidst the warnings of Jordan Peterson and Co. there seems to be a lack of recognition that human desire points to something—it is an invaluable clue—about who and what we fundamentally are. Young men are not taking responsibility for their lives, yet the reason might be more complex than laziness or their social benefits package. Truthfully, although of different temperaments, men generally have a desire to do something exemplary, to be virtuous, to be honored, yet this potential is brutally short-circuited by their education and the cultural ideology they’ve inherited. The innate human desire for more which plays itself out in all the familiarly destructive ways is not in itself a problem, rather, this desire is being misdirected. It is an old problem, with an old solution, but I’m not going to go back to Aristotle just now.

William Blake said that a grain of sand perceived properly would open one up to eternity; cleansing the doors of perception is the task of the modern man—until we begin to see clearly again who and what life, man, children, education, work (etc.) truly are, we will continue to mistake the temporal for the eternal, the finite for the infinite, and such will never satisfy, leading to the despair, nihilism, and “laziness” so rampant today. I myself worked a typical production job not too long ago, and after two weeks of repeating the same actions on the assembly line, 8-12 hours a day, I too began to have a hard time getting out of bed. It was not laziness which caused this but the utter disillusionment I felt as I realized I would be spending the majority of my waking hours doing something a robot could do just as well. If my job could be easily replaced by robotics, it was robotic to begin with. I could no more be blamed for being lazy than a plant stuck in a dank broom closet could be blamed for feeling droopy.

What can be done about all this? I’d propose that a mass awakening is not coming, and that folks should do what they can, with what they have, where they’re at. I think of this as sowing seeds; the wider reverberations of our actions are out of our direct control, but regardless how bleak the situation may currently be, there is no excuse for abdicating our role in society to set the shining example of a beautiful life befitting of a human being, marked by living in accordance with one’s human nature. What practically anyone can do is assess their life and make steady little adjustments, and what (nearly) everyone has is a human mind, heart, and hands, capable of expressing that which lives and burns within them.

The good news is, it is relatively easy to stand out in a positive light at the moment—simply not using ChatGPT in order to actually exercise one’s mental faculties to solve a problem will raise plenty of eyebrows, and foregoing the next promotion to start raising children is sure to get the attention at least of family and some friends. My wife and I enjoy the confused and slightly alarmed looks we receive when people find out our children prefer to read than watch the TV. And if enough folks choose to begin living like human beings again, people might just begin to believe that they have a choice in how they live too, which in turn might cause a few to begin making decisions based on value and not merely desire, which is after all what separates man from beast. We are not wholly constrained by the biological and chemical restrictions incumbent upon us, and perhaps the knowledge of this fact will trigger a return to sensible living and a more beautiful, humane living environment—the choice is ours, if we believe it to be.

1 comment

Amy

I loved this article. I’ve been de-machining my life very slowly over the last year and have become a bit of a bore about it. What I’ve been surprised by is how receptive people are and how so many are looking for ways to regain their humanity.

Comments are closed.