For much of the previous three years, my daily commute has been filled with audiobooks. With a mixture of enjoyment at the narration and guilt at the irony, I often listen to the words of Wendell Berry’s fictional Port William series flow through my vehicle speakers. After finishing another Berry novel, my app prompted an examination of “Related Artists” to find my next book. Featured alongside recognizable names such as Marilynne Robinson and James Herriot was an unfamiliar one: Halldór Laxness. The singular book available was Independent People. After reading the attached summary describing the story of a sheep farmer and his “flinty determination to achieve independence,” I began to listen. Readers meet the Icelander Bjartur of Summerhouses newly married and, after nearly twenty years of tenant shepherding for the local magistrate, recently settled upon his own land, for which he has borrowed considerably to purchase. The story follows Bjartur’s struggle to make a living off the land despite the government, weather, parasites, and markets all while losing his family in the process.

Brad Leithauser’s 1985 essay served as the introduction for this edition. Originally published in The New York Review of Books, the essay gushes, “There are good books and there are great books, and there may be a book that is something still more: it is the book of your life.” Published in 1935, Independent People arrived early in a writing career which would eventually earn Laxness a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955. Blacklisted by Washington at the height of his renown due to his explicit Stalinist sympathies, Laxness has experienced somewhat of a renewal in American literary conversation in recent decades.

Upon completion of my listening to Independent People, it occurred to me that the content of Halldór Laxness’ story is essentially unrelated to that of Wendell Berry. One acquainted with Andy Catlett of Port William would recognize Bjartur of Summerhouses as familiar in setting, but foreign in substance. In their depictions of affection and community in rural life, Berry and Laxness position their characters quite differently. One should note, I write here merely as a casual reader contrasting characters, not as a literary scholar critiquing themes of socialist ideology or familial complexity. Here we will take Laxness’ characters at face value, regardless of whether they were meant to serve more as a critique than as a model.

Community

Today, many tourists plan their travel to Iceland in conjunction with réttir, the annual roundup of the Icelandic sheep flocks from their summer grazing in the high hills. Visitors spectate in awe at the remarkable collaboration between man and dog as neighbors gather to sort sheep, often employing the same methods and ancient stone structures as their ancestors. Such scenes of communal work are woefully absent from Laxness’ work. The critic Leithauser remarks a truer English translation of the title might be Self Standing Folk, and perhaps this wording more accurately captures the novel’s ethos. Bjartur’s farm is an island unto itself. Indeed, there are scenes of community and relationships throughout the work, but their presence is often met with disparagement. Bjartur drinks, exchanges poetry, and talks sheep with his fellow farmers, but his conversation is marked by condescension and contention. Bjartur is a man apart and rejects any collaboration as weakness. I’m not sure Bjartur has someone he’d call a friend. As for his family, he shows little affection for his wife or children as he works them into the ground in an effort to climb out of debt.

Leithauser’s adoration of Bjartur was met with surprise by Laxness as the author described his own protagonist as “stupid.” For my own part as a boy who bonded with his father over John Wayne films, the roguish isolationism of Bjartur initially warmed my heart. I nodded enthusiastically as I listened to his monologues against the merchants and government. I identified with the desperate drive to rid himself of debt with a fervor that would make Dave Ramsey proud. I also shared Bjartur’s affection for sheep. But for all this, the obvious absence of meaningful relationships in Independent People is poignant. He has no one with whom to share this life he’s furiously building. Bjartur’s mission to rid himself of reliance causes him to sever any meaningful relational attachment.

The work found in the tobacco fields of Port William is in essence quite different than the work found in the sheep-filled hills of Iceland; however, the community depicted in Berry’s fiction is both realistic and idealistic. Contention and condescension are not entirely absent from the relationships of Port William, but collaboration defines the community. The descriptor given to the interwoven lives of Port William is membership. Membership is the chosen term Berry employs to define a people who value the same things and identify with one another. Being a member inherently communicates both responsibility and privilege. Berry’s characters do not exist independent of one another; they walk the paths of joy, pain, toil, and triumph together. Whether in the fields of Nathan Coulter’s tobacco harvest or Jayber Crow’s barber shop or Wheeler Catlett’s law office, Berry’s exemplary characters rely on, commune with, and work alongside one another. Bjartur shows only contempt for such collaboration. Berry’s characters know and are known by their neighbors. The narrative overwhelmingly communicates that the lives of the characters are enriched by their dependence on others.

Affection

Freedom is obviously the primary motivation for Bjartur’s work, but one might be tempted to think freedom from the magistrate drives his work far more than anything he would be free for. Farming for Bjartur is the only way of life he’s known, but there doesn’t seem to be a particular facet of the agrarian life that connects him to the land. This negative freedom is a dead-end. Despite being a small-holding agrarian, Bjartur in many ways embodies the cold, calculating nature of Laxness’ dreaded capitalism as he continues his “crushing, ruthless drive for self-sufficiency.” This drive is most heartbreakingly clear in Bjartur’s treatment of the calf from the family’s milk cow. The scene captures the reader due to its uniqueness in comparison to the rest of the narrative. Life at Sommerhouses halts and then transforms at the calves’ birth. All except Bjartur are enamored with the newborn calf, even the dog greets this new arrival with unusual politeness. Laxness describes the scene:

[E]veryone was so happy because of this new personality on the farm and thankful that everything had gone so well with the cow, when everyone was sharing so intimately in the cow’s happiness…The days that followed, they were great days…[the children] had fallen in love with the little bull and were never done fondling him (IP. 225-226).

The family’s joy at the calf is only eclipsed by their sorrow at the cruelty of Bjartur as he awakens the house to announce the location of the entrails of the now butchered animal before taking the small carcass to town. In a practical sense, Bjartur viewed the calf as a possible encroachment on his pursuit of independence; however, the way in which he approaches the matter is absent of any consideration for his family’s joy much less an appreciation of beauty.

Whereas Laxness presents us with brutal realism in his depiction of agrarian life, Berry offers us not naive sentimentality but realism oriented toward a vision of the good. The closest thing to sentiment is perhaps the description of the old horse in Nathan Coulter: “He’s been a wheel horse in his time. He’s worked liked the world was on fire and nobody but him to put it out. It’s a shame to see him getting old.” Animals are rarely ascribed human characteristics in Port William, but their existence is recognized and appreciated just as Wheeler Catlett often longs to leave his office to enjoy seeing his cattle graze on grass in the eventide. There is a fullness in the work done in Port William and in people at work together. Affection sustains this arduous life of work. Wendell Berry articulates the vision which compels a fulfilling life on the land:

‘Why do they do it?’ Why do farmers farm, given their economic adversities on top of the many frustrations and difficulties normal to farming? And always the answer is: ‘Love. They must do it for love.’ Farmers farm for the love of farming. They love to watch and nurture the growth of plants. They love to live in the presence of animals. They love to work outdoors…They like to work in the company of their children and with the help of their children. They love the measure of independence that farm life can still provide. (Bringing it to the Table 94,95).

Living close to the land presents its challenges, yet it offers a richness that can only be truly savored within the embrace of community and affection. Seen through his most redemptive lens, Bjartur stands as a cautionary tale for those who would pursue independence as an end in itself. For readers of Port William, Laxness is certainly worth the read, but Berry offers the more compelling and complete vision.

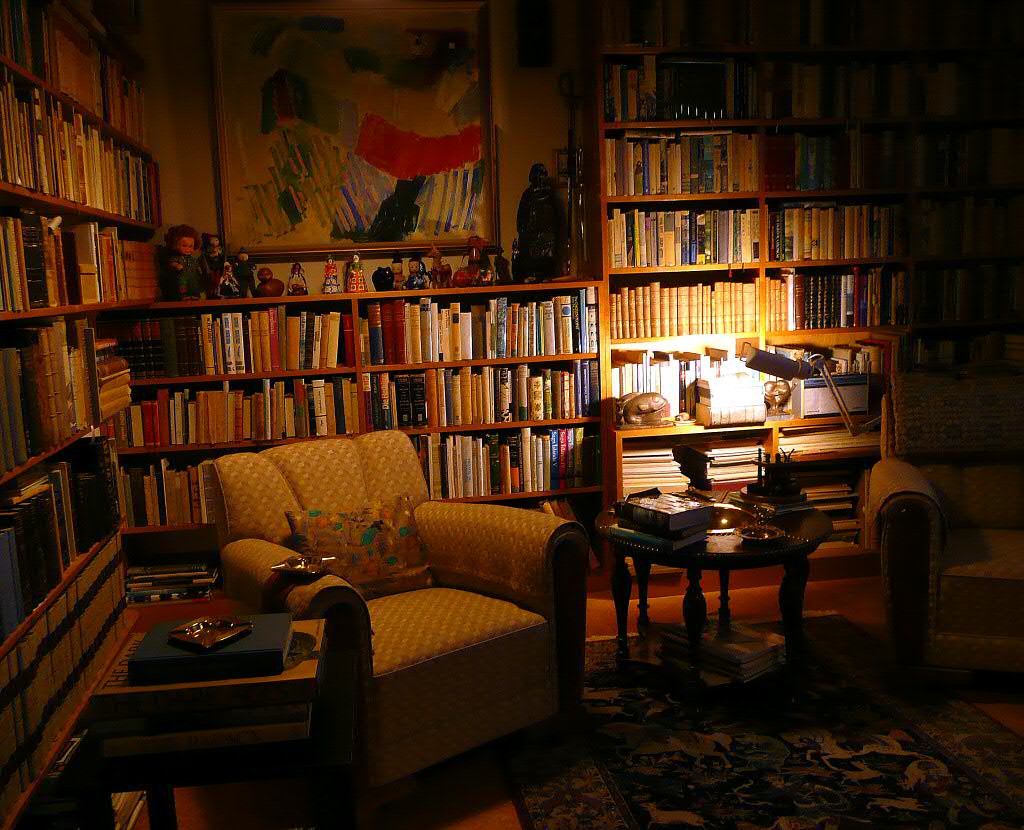

Image via Flickr