This is an excerpt from Alex Sosler’s new book, A Short Guide to Spiritual Formation: Finding Life in Truth, Goodness, Beauty, and Community.

Saint Anthony was once asked, “What must one do in order to please God?” “He replied, “Pay attention to what I tell you. Whoever you may be, always have God before your eyes. Whatever you do, do it according to the testimony of the holy Scriptures. Wherever you live, do not easily leave it. Keep these precepts and you will be saved.” Those first two pieces of advice are standard enough. But that third one hits the modern person differently. Anthony doesn’t say never to move, but he does say not to leave easily. I think that’s rich advice to heed in today’s world. Sometimes, there are good reasons to leave a church—whether that be dysfunctional or unhealthy church leadership or an intriguing opportunity in another city. But I think our overall tendency should be to stay. Church is a place of commitment—starting with our baptismal vows. And commitment is scary.

In a documentary called Godspeed, a film about slowing down our pace of life and getting to know neighbors in a parish sense, there’s an interview with a monk. Benedictine monks take a vow of stability, promising to stay in the same monastery their whole life. In our mobile and global age, I know that sounds unthinkable. No travel? No exploration? Just stuck in the same spot? Yes. For these monks, commitment to place is a spiritual matter.

The monk who is interviewed, Father Giles, says the secret to stability is the realization that one is a sinner but a beloved sinner. He says, “Very quickly, you see people’s faults. Look at that guy. But to see people’s virtues, it takes longer. To learn to know takes time.” He explains that modern culture may be obsessed with the “shallow novelty” of new experience, but deep relationship takes time. Later, he talks about growing with these brothers in place as an opportunity to see the grace of God at work. “You see Brother So and So. You can’t get within two miles of him.” But after ten years you can get within a single mile. And after twenty years a half mile. And after forty years maybe six feet. And if God can do that, what graces may he have at work within me?

Often, when a conflict occurs in my life, I am quick to leave. If a leader makes a decision I don’t like, I’ll go someplace else. Or if that lady seems arrogant and rude, I’ll think that this isn’t the right church for me. Or those guys seem closed off and distant, so let’s get out of here. I can choose to live like that, but I’ll never stay any place long enough to truly know a people, and therefore, I can never really love anyone or receive love in return. Worse, I’ll never stay long enough to see the grace of God at work. Wendell Berry suggests we should carry forgiveness like a fire extinguisher. “If two neighbors know that they may seriously disagree, but that either of them, given even a small change of circumstances, may desperately need the other, should they not keep between them a sort of pre-paid forgiveness? They ought to keep it ready to hand, like a fire extinguisher.” The problem of many communities is that we live like we don’t need one another. We think we can move on and not care. We don’t live with affection, and we therefore have no prepaid forgiveness.

Stability is important for church life, and it’s also important for neighborly life. In other words, stability is not merely a commitment to a holy huddle but can also be a commitment for stewarding a communal shalom.

People aren’t disposable. Places aren’t the same. Sure, I can make new friends, but I’ll never have friends like Nick, Danny, Logan, Jack, Matt, and Ben, because they’ve known me the longest. They knew me in my foolish high school years. They’ve seen me grow. They have loved me when I felt unlovable. I’ve made new friends, but I can’t replace my day-one homies.

Likewise, I could never have friends like Jonathon and Gary if I left Asheville, North Carolina. Our friendships are distinct. We’ve shared life together, cried together, worshiped together. Even if I move to a different house within the same city, I’ll never have neighbors like Luis and Marianne. I can meet new neighbors, and perhaps they’ll offer unique gifts. But Luis makes tacos for my family when my wife is sick. Luis introduced me to the wonder of Oaxaca, his home region in Mexico, and its signature export, Mezcal. Their lives and friendships are gifts that are not replaceable.

As I talk about stability, I can’t promise I’ll never move, but I always want to live in a place as if I’ll be there forever. Doing so commits me there. Commitment also makes it hurt to leave. It should feel like I’m being ripped out of a web of connections if I leave a place, because I am. If I lived in a place and it didn’t hurt to leave, then I don’t think I ever cared for it or was nourished by it. If I’m not caring for a place and people, then my love for God is mental and ethereal but makes no impact on where I live. I’m not sure that’s the kind of peace and healing that God is passionate about bringing to earth.

In the aftermath of the first sin, the reaction is to shift responsibility. God asks Adam, “Who told you that you were naked?” (Gen. 3:11). Adam points his finger: “The woman whom you gave to be with me” (v. 12). When Cain kills Abel and God comes looking, Cain asks, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” (Gen. 4:9). The implied answer to this rhetorical question is no, but the real answer is yes. Yes! You are your brother’s keeper. When Christ comes, he comes bearing the guilt as his brother’s keeper. He takes responsibility. Spiritual formation is misguided and distorted if you don’t bind yourself to a connected community, which includes the land and all living creatures.

We are placed beings. We are taken from the land, and we feed on the land. We cannot avoid the truth that “our land passes in and out of our bodies just as our bodies pass in and out of our land” and that all the living “are part of one another, and so cannot possibly flourish alone.”[1] We are in a web of existence that includes not only the church and our neighbors but also the very dirt we live from. Creation care is therefore spiritual formation. Caring for the land is stewarding God’s gifts to us. Every created thing is loved by God. But we will not love what we do not know. As Wendell Berry writes in “Native Grasses and What They Mean,” “To see and respect what is there is the first duty of stewardship.” Perhaps the reason we don’t care much about the maintenance of what we’ve been given is that our hands seldom touch the land. We drive on pavement and walk on cement. Part of the creation mandate of Genesis 1 is ecological care as an act of dominion—not dominance but watchfulness.

On the subject of living into place, the theologian Norman Wirzba proposes, “If you want to be with God, don’t look up and away to some destination far beyond the blue. Look down and around, because that is where God is at work and where God wants to be. God does not ever flee from his creatures.” God meets his creatures where they are. God is not around the next bend, at the next big event. God is here, among us, desiring to meet us. Adam is taken from the adamah, the ground. Humans come from humus. God inspires the dirt to create humanity. We’re called to toil and serve the dirt we came from. We’re called to nourish the places that have nourished us. Often, however, we forsake the dirt and fail to live with the land. We exploit and erode our genesis.

In an interview with nature writer Barry Lopez, Fred Bahnson asked about Lopez’s time in the 1970s and 1980s among the Inuit population in the Artic. Lopez asked what adjective these indigenous communities would use to describe white North American culture. The word he heard again and again was “lonely.” “They see us as deeply lonely people,” Barry told Fred, “and one of the reasons we’re lonely is that we’ve cut ourselves off from the nonhuman world and have called this ‘progress.’” Maturity in Christ is not escape but presence.

Early in my spiritual life, I knew to care about the land, but I did not care to know about the land. And those few swapped words make a world of difference. The modern world encourages us to try to live as disembodied entities, disconnected from both time and place. We may feel like technology gives us access to every place, but every place is no place. Likewise, every time is no time. Because I buy my food in a package at the grocery store, I am disconnected from the earth and its corresponding seasons, rhythms, and cycles. I don’t know the effects of extended drought or what season certain vegetables grow in. I go to the supermarket, and every season is no season.

“People exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love,” Berry argues in Life is a Miracle. “And to defend what we love we need a particularizing language, for we love what we particularly know.” An agrarian mindset invites us to nourish life in holistic ways: creating vitality of land, creatures, and people together. It invites us to care for and to love our place and our neighbors. Where we are is where God wants to meet us.

-

Berry, Unsettling of America, 22. ↑

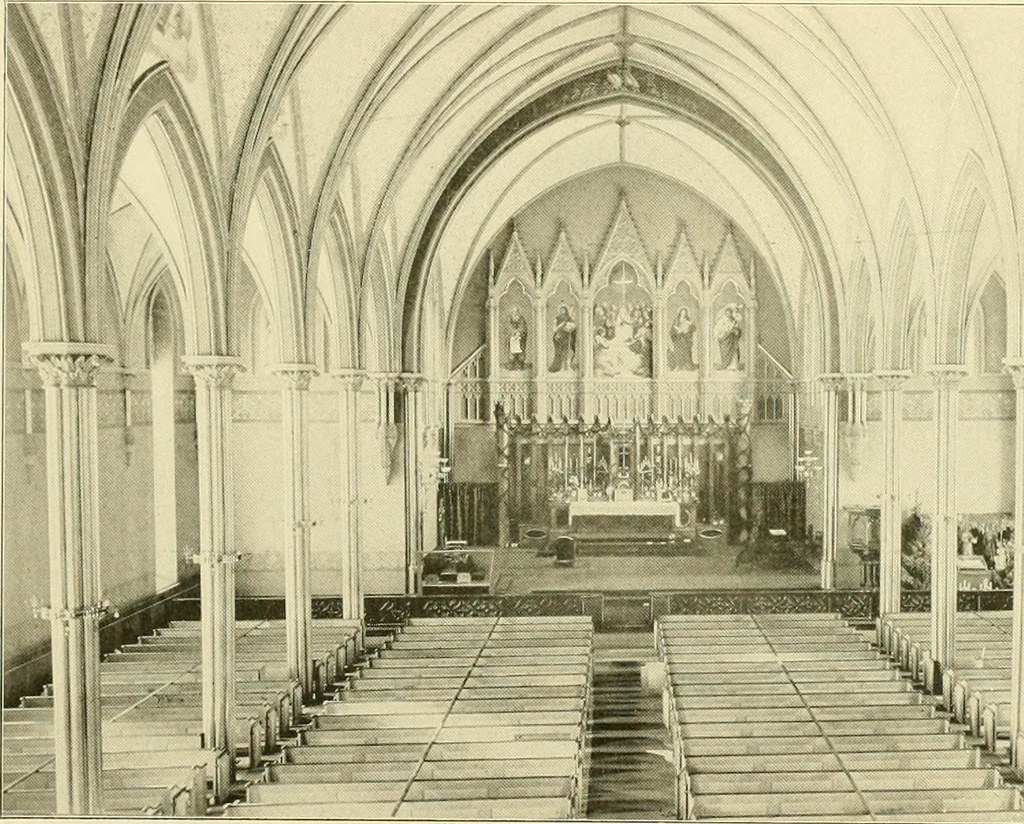

Image via Flickr