Sometime in early middle school, I remember briefly interrupting my steady diet of Nancy Drew mysteries in Hebrew translation, which my best friend Hadar and I checked out by the dozen each week from our school library. I can still visualize that small building, its low ceilings, the wall of shelves where all our favorite mystery series resided. It had that distinctive old books smell—a mix of mildew, dust, and je ne sais quoi—that sets a bookworm’s heart aflutter.

Instead of mysteries, though, for a reason I do not even recall, one week I checked out Dvorah Omer’s novel Tears of Fire, set during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Only in Israel, I think in retrospect, would twelve-year-olds be this intimately familiar with the history of the Holocaust, the violence and suffering of oppression in the Warsaw Ghetto, and the horrifying events of the uprising and the final destruction of the ghetto. But then, everyone in the class, myself included, had lost at least some relatives in the Holocaust.

I did not know at the time of Omer’s own mournful family history. Having lived her entire life in Israel—although born in a kibbutz in the land before Israel officially existed—Omer suffered much. She found catharsis in her art, it seems, as a children’s and YA writer, composing novels that covered two extremes. In Omer’s works, it is either AI-perfect kibbutznik families of the sort she wishes she had but never did experience, or orphans dying in an oppressed war-torn ghetto. There are no in-betweens in her fiction.

Omer’s own immediate family tragedies were not rooted in the Holocaust. And yet, like all Israeli Jews of her generation, she could not help but think about it, dreaming powerful nightmares that became her novels. In retrospect, reading more about her life, I wonder if she was fighting all her life to recover scenes from her stolen childhood—the loss of a father to divorce in infancy, and the tragic death of her mother when she was just eleven years old.

The Polish writer Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz was born in 1935, just three years after Omer, and lived in some ways a parallel life to hers, but in Poland. There is a key difference, though, between Rymkiewicz and Omer: Rymkiewicz was not a Jew. Still, living in Warsaw of WWII and the Holocaust, he could not avoid seeing everything that was transpiring around him, even as his own life was technically deemed safe.

Now available in English translation from Slant Books, Rymkiewicz’s unusual memoir, Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood) brought to mind Omer’s novel of children’s lives in Warsaw. Here is a real little boy who lived through unspeakable horrors all around him—except decades later, of course, he did find words to write of them. Staying alive is a gift, even if it might not feel like it at the time.

His memories are plagued by profound loneliness. Childhood is defined by presence—of parents, of adults who should keep the child safe, allowing him to be a child. War, however, creates nothing but absence, stripping people away from places, and places of their previous inhabitants. Many will never return, and those who do, will never be the same. He is, in some ways, one-of-a-kind: the one who did not leave during the war, and then decided to stay after.

A prolific writer in his native Polish, Rymkiewicz, who passed away in 2022, was best known for his poetry. Yet he was remarkably versatile. His works include two novels, numerous essays of literary criticism, and translations of poetry from both English and Spanish. And then there is this memoir. It is no straightforward linear narrative but reads more like a series of essays. Short chapters describe disparate episodes, observations, moments that come across as vestiges of fevered dreams—except they are genuine memories.

The effect is more powerful than any matter-of-fact narrative could offer. A reader is left to mourn and wonder: how could a child make it out of such horrors alive and with any faith left in the beauty of life and art? And how could he bear to remain in that city for the rest of his life—that place where each street was associated for him with someone’s death? Or was it staying there that powered his writing, the quest for beauty to overwrite the ugliness he had seen?

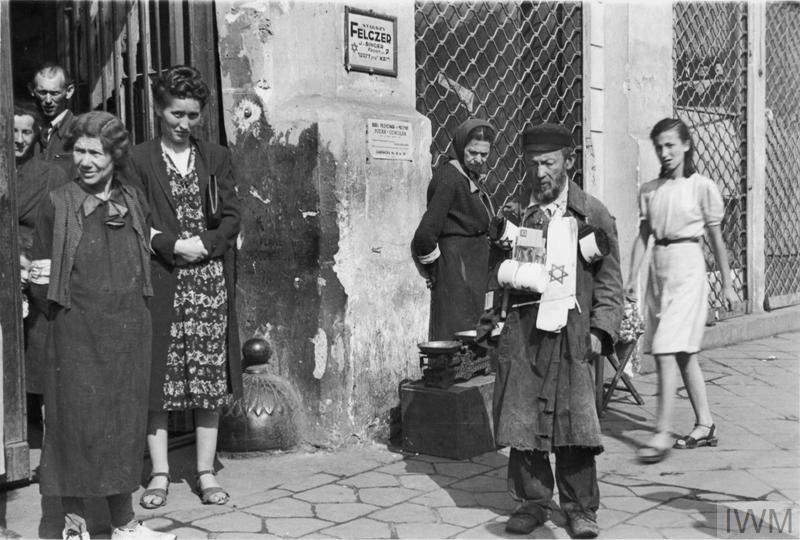

Books like this one offer an added significance, complicating our assumptions about how different groups of people experience horrors through which they must live, even if as passive observers. A simplistic narrative of the Holocaust divides occupied territories into two categories: Jews (victims) and all others (somewhat safe). But Rymkiewicz’s narrative of his experiences shows how uncertain and threatened the lives of all under occupation truly were. We know that for Holocaust survivors, their experiences were unspeakably traumatic and plagued them for the rest of their lives. But what about someone who was but a child, playing in the streets as war raged all around, because he could think of nothing else to do? Of course, had the child been a decade older, he would have been drafted into the war, forced to turn a killer—just as so many ordinary Polish men were.

It’s not only in words, though, that we process the past and remember childhood, even a childhood that is traumatic. The isolated scenes that form this book all come through a child’s eyes, but not exactly. Rymkiewicz wrote this memoir decades later, as an old man and a lifelong writer, thinking back to the child he was with the eyes of an artist. The title emphasizes the artistic nature of these remembrances.

The memoir’s title, left untranslated, is a nod to Robert Schumann’s collection of pieces for piano by this same title. In Schumann’s collection, the pieces are meant for children—the difficulty level is fairly low, perfect for an early intermediate pianist. They tell through music stories like “An Important Event,” “Knight of the Hobbyhorse,” and the concluding “A Poet Speaks.” And so, in a strangely playful manner, in the final chapter of this book too, the poet speaks as he considers “The Death of a Turtle.” He reminisces in conclusion about the familiar music of his childhood—the bells of city trams:

These days the trams don’t ring bells; back then, they did… I can even say that I’ve lived out my long life in two civilizations—one civilization where trams have warning bells and one civilization where they don’t.

It seems that we can feel nostalgia even for a childhood defined by trauma, war, the unspeakable. The sounds of childhood in hindsight are precious simply because they were the soundtrack of our formative years. There is nothing intrinsically special about the ubiquitous sounds of street trams. But in the memory of childhood, they acquire a defining meaning that shaped an era, a time of innocence that should have been, but was denied.