Sigmund Freud told mourners to get over it. Then his daughter died. It is seldom reported, but the heartbroken doctor changed his views completely after losing a child. Over time, Freud displayed a compassionate understanding of the continuing bond that exists between parents and their dead children. He soon dismissed the idea of moving on after a loss.

Freud was no stranger to grief. The passing of his younger brother, Julius, aged six months, three weeks before Freud’s second birthday, contributed to years of remorse. When Freud was forty, his father Jacob died in 1896 at the age of eighty-one. This led to a lifelong engagement with self-analysis: evaluating and re-evaluating the impact of death.

In 1917, Freud wrote his influential Mourning and Melancholia. In the paper, he defines mourning as a severing from an object (our loved one) that no longer exists. An inability to detach, he suggested at the time, is pathological grief. This attitude is difficult to understand with his younger brother, and it calls into question Freud’s complicated relationship with his father. The paper continues to influence a surprising number of modern grief books.

But loss changes us.

On January 25, 1920, Freud’s daughter Sophie died from pneumonia after a bout with the Spanish flu, one day before her seventh wedding anniversary. She was twenty-six, a mother of two with a third child on the way. “Our dear Sophie in Hamburg had been snatched away . . . as if she had never been,” Freud wrote a friend. “The undisguised brutality of our time weighs heavily on us. Our poor Sunday child.” Shortly after Sophie’s death, on February 4, he wrote, “Quite deep down I can trace the feelings of a deep hurt that is not to be healed.”

Freud decried to his daughter’s husband, Max, the senselessness and brutality of a fate that took Sophie, adding, “One must bow one’s head under the blow, as a helpless, poor human being with whom higher powers are playing.” Later, he confided to a friend that poor Max “will have to pay dearly for the happiness of these seven years.” Payment was due for the love they shared, of course, and for something else.

Such statements are quite common in the first onslaught of acute grief, when mourners flail about, seeking explanations for the death. Usually these reasons are tied to blame, guilt, and self-recrimination.

My daughter Jess died in 2015 of a fentanyl-laced heroin overdose. As with many parents, I too possess a mantra of remorse: my failures as a father; the times I wish I had behaved differently or spoken with greater kindness. Such ruminations are fruitless and harmful. “Things can no longer be undone,” observes grief counselor and bereaved parent Harriet Sarnoff Schiff. “Reviewing mistakes is of less than no value when reliving the time spent with your now dead child.”

A number of bereaved parents have reported feeling that personal transgressions led in some terrible way to the deaths of their children. Their guilt is usually tied to the seven deadly sins or one of the Ten Commandments, most frequently adultery, theft, deceit, and greed. These emotions are nearly universal after losing a child.

Bereavement experts have identified five common sources of self-recrimination: cultural role guilt (Was I good parent?); death causation guilt (Did I cause her death?); moral guilt (Wasn’t I good enough?), survivor guilt (Why her and not me?), and recovery guilt (I don’t deserve to be happy). Many of us know these feelings well.

Moral guilt is my poison of choice.

Every book I have written was dedicated to Jess: computer and translation texts; histories; and after she died, two books on grief. Jess was tickled with each of them except one volume that led to my conviction for criminal impersonation. Her disappointment and sense of betrayal were excruciating, as are my sorrow and remorse. In the first year after Jess died, I was certain that her overdose was my fault: that she paid for what I did or what I failed to do. I even convinced myself that I was to blame for her addiction.

This is damaging nonsense, of course. Consider how insulting it is.

Jess was twenty-six years old, a grown woman with her own attitudes and experiences, her own choices. She would likely have scoffed at my hubris. In the skewed memory of narcissistic guilt, I was dismissing her as a person, treating her as if she were an extension of myself. As time passed I saw the absurdity of this thinking, but it took some doing.

Part of healthy grieving includes a stark realization of the false perceptions we hold of our loved ones and ourselves. Another bereaved parent, Albert Zandvoort, a psychotherapist at the University of Witten, suggests that our feelings of anxiety, guilt, and grief need not be destructive. Instead, he writes, they may “provide the traumatically bereaved individual with opportunities for growth and creativity.”

For seven years I resisted the idea of any sort of “benefit” from my loss. The idea seems repulsive and grotesque. I was wrong. “Grief—or perhaps better, psychic pain—can also give us strength,” observes Kathleen Woodward, Director of the Simpson Center for the Humanities. “There are times when we do not wish to, and should not, willingly yield it up.”

Freud may have agreed. His thoughts on mourning from 1917 were unequal to the reality of grief. “No sooner did he formulate this conception, than he put it into question,” observes L. Scott Lerner of Franklin & Marshall College. It was after the death of Sophie, writes Tammy Clewel, of Kent State University, that Freud redefined what he called melancholia as an integral part of bereavement. He realized that sorrow does not come to a precise and measurable end. “Freud’s later work registers the endlessness of normal grieving,” Clewel concludes, “to suggest the affirmative and ethical aspects of mourning.”

In The Ego and the Id (1923), written three years after Sophie’s death, Freud resists his initial idea that we must separate ourselves from those we have lost. In mourning, he writes, our mind readjusts to a new reality. Our sense of identity, or ego, is structurally altered to continue an equally important identification with the person we have lost. He added that this is “the sole condition” under which we can accept our loss.

It is not our sense of identity alone that continues the relationship. Apparently, our brains are hard-wired this way, suggests Mary-Francis O’Connor, who studies grief at the University of Arizona. While our loved ones are alive, our brains devote tremendous energy to mapping their locations so we can find them in times of need. “Grieving requires the difficult task of throwing out the map we have used to navigate our lives together,” O’Connor notes. “And transforming our relationship with this person who has died.”

Modern research has confirmed that mourners often experience a sense of transformation, transcendence, and compassion that they had not experienced before. Often, reaching out in service to others is not an altruistic duty; rather, it is an act of survival and love: a means to get outside ourselves and to honor the memory of our dead. Freud was no different.

One month after Sophie’s death, on February 24, 1920, Freud opened the first free psychoanalytic outpatient clinic in Berlin. The idea was suggested to him by Max Eitingon and Ernst Simmel. Opening the hospital at such a crucial point in his life, Freud wrote, was “the most gratifying thing at this time.”

All too soon Sophie’s son, Heinz, called Heinele, also took ill. Freud adored the boy, calling him “the cleverest, sweetest child I have ever met,” and noting in 1922 that although Heinele was physically fragile, he was especially bright and endearing.

Heinele was staying with his aunt Mathilde (Math) and uncle Robert Hollitscher when he died of miliary tuberculosis on June 19, 1923, after three weeks’ illness. The loving grandfather was shocked at this loss and also by Heinele’s peculiar prescience. “He too was of superior intelligence and unspeakable spiritual grace,” Freud was to write in 1928, “and he spoke repeatedly about dying soon. How do these children know?”

Freud had placed much of his love for Sophie in Heinele, perhaps as a way to honor his daughter, and even more so for Heinele himself. “For me, that child took the place of all my children and other grandchildren,” Freud wrote. “When little Heinele died . . . I became tired of life permanently.” This led to three weeks of near-constant weeping and “some of the darkest days of my life,” Freud told the boy’s father, Max.

Freud’s subsequent letters during this period reveal an astonishing litany of lament.

“He meant the future to me,” Freud told Oscar Rie, “and thus has taken the future away with him.” Ernest Jones, Freud’s lifelong colleague, observed that Hienele’s death was the only time his friend had shed tears. Freud told him that the loss affected him differently from the others he had known. “They had brought about sheer pain,” Jones recalls. “But this one had killed something in him for good.” Freud told Marie Bonaparte that now he felt incapable of loving anyone again. He confided to his friend Sándor Ferenczi that though he had never suffered from depression, this must be what it feels like. He saw only darkness ahead. “The loss is excruciating for me,” Freud wrote to Kata and Lajos Lévy on June 11, 1923. “I doubt I’ve ever known such overwhelming grief . . . I work out of necessity; ultimately everything has lost its meaning.”

These emotions are not only expected, healthy, and normal; they are also a natural reaction to death. Freud loved Sophie and Heinele. His grief was a continuing aspect of that love.

In expressing his love through epistolary lament, it may be that Freud discovered the precise meaning he felt he had lost. Ten years after Heinele’s death, he remained a doting grandfather. When poet and novelist Hilda Doolittle began therapy with Freud, now seventy-seven, she despaired that he was forever wondering aloud, “What will become of my grandchildren?”

Back in July, 1925, five years after Sophie’s death and two years after Heinele passed, Freud wrote one of his most influential works, Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety (1926). The first section is titled “Modification of Earlier Views,” a theme that runs throughout the book. In the final chapter, “Anxiety, Pain, and Mourning,” the bereaved father and grandfather asks a question that never seems to have been far from his mind: “When does separation cause anxiety, when does it cause grief, and when, perhaps, only pain?”

Perhaps not only pain. Freud also expressed love.

“My daughter, now dead, would have been thirty-six years old today,” he wrote on Sophie’s birthday, April 11, 1929, nine years after her death. He was offering advice to a friend that had recently lost a son. “Anything that fills this emptiness, even filling it completely, will forever be something else,” Freud said. “Our acute grief may pass, but we know that we will remain inconsolable, never finding a substitute. And this is how it should be. It is the only way to continue a love that we would never forsake.”

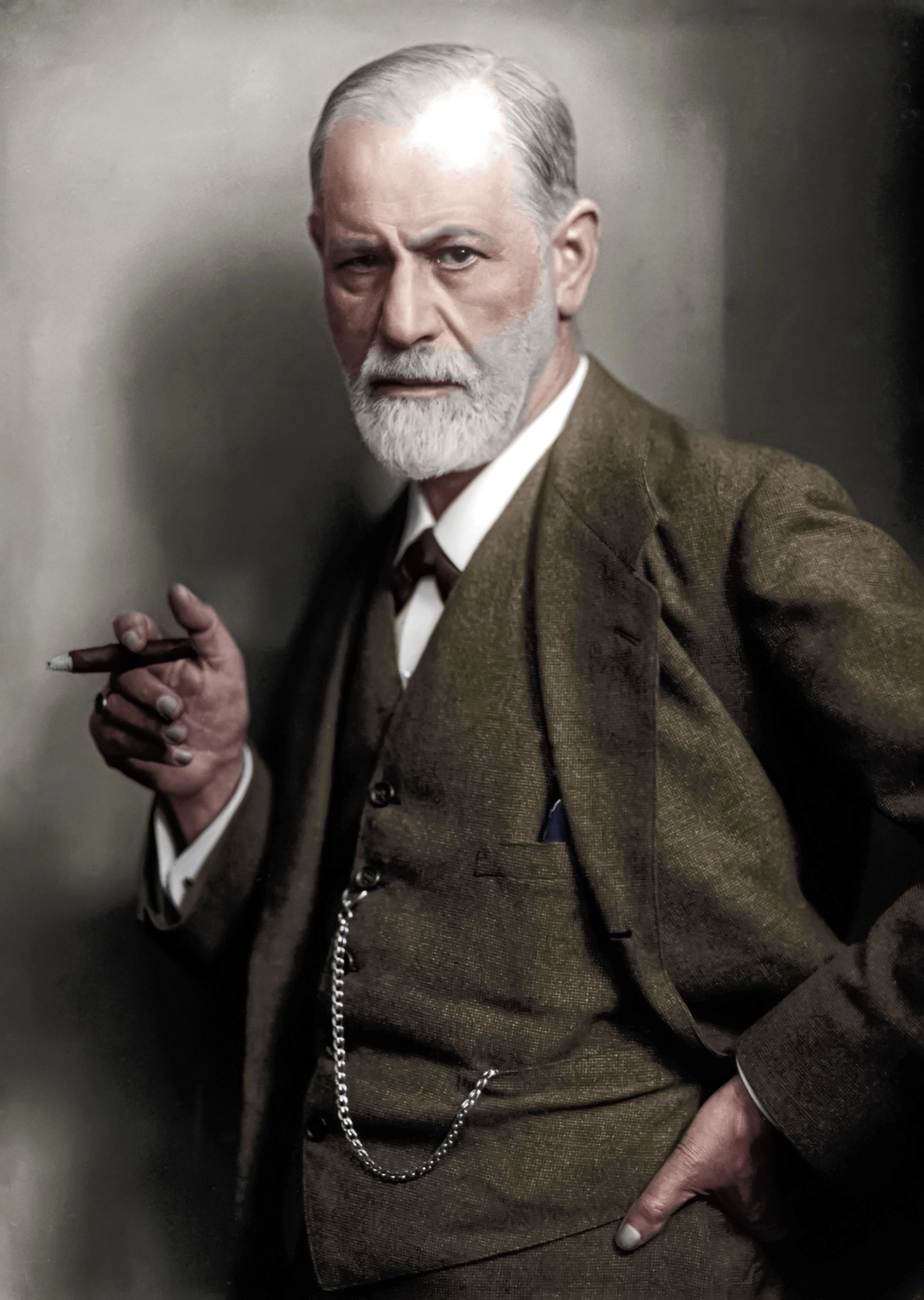

Image via Wikimedia Commons