It’s an ancient theme, that man, each man and all men, and all their works shall die. – J.R.R. Tolkien

Vilonia, AR. It was British historian and folklorist Francis Young’s “The Myth of Medieval Paganism” that made me think about the collaboration between Johnny Cash and Trent Reznor on the iconic song “Hurt.” Young’s research challenged what it meant to be pagan (and I had considered Reznor to be of that ilk). In the Middle Ages, “pagan” was a derogatory term used by urban Christians to describe rural Christians who still (presumably) worshipped the ancient gods. The Latin pagani denotes “rural persons” or, more colloquially, a “country bumpkin” or “hillbilly.” Instead of hunting heresy, Young emphasizes the “inventiveness and eccentricity” of pagan seeming practices as simply a result of an imperfectly catechized Christian culture—or perhaps just “very strange expressions of Christianity.”

I prefer Young’s second surmise. It is precisely the strangeness of a thing that paradoxically makes it both more and less familiar. Taken seriously, the monstrous gargoyles, grotesques, and green men carved within and without the cathedrals as symbols signaled the way things “are”—not just the way things “were.” The uneasy coupling of pagan and Christian ideas was not simply an artful flourish or nod to former Thor worshippers. For J.R.R. Tolkien, monsters are more real precisely because they belong to that other world where strange is commonplace, the world we moderns deem fantastically unreal, superstitious even, dare I say—hillbilly (and I consider Cash to be of this ilk).

Ken Burns’ documentary Country Music depicted the little-known history of this story-laden genre first dubbed “hillbilly music.” It was a mix of lyrics about honky-tonks, fornicating, poverty, and Jesus, with biographies of fame, fortune, divorce, death, destruction, and Jesus. Cash understood what it was to live in the pain, and so did his fans. According to Colin Edward Woodward, although “Johnny always thought of himself as a Christian, and he recorded piles of spiritual music, …his gospel…songs never sold as well as the ‘outlaw’ material.” Hillbillies and pagans, both monikers of derision, understand one another—perhaps because they are both outlaws and at times, monsters of their own making.

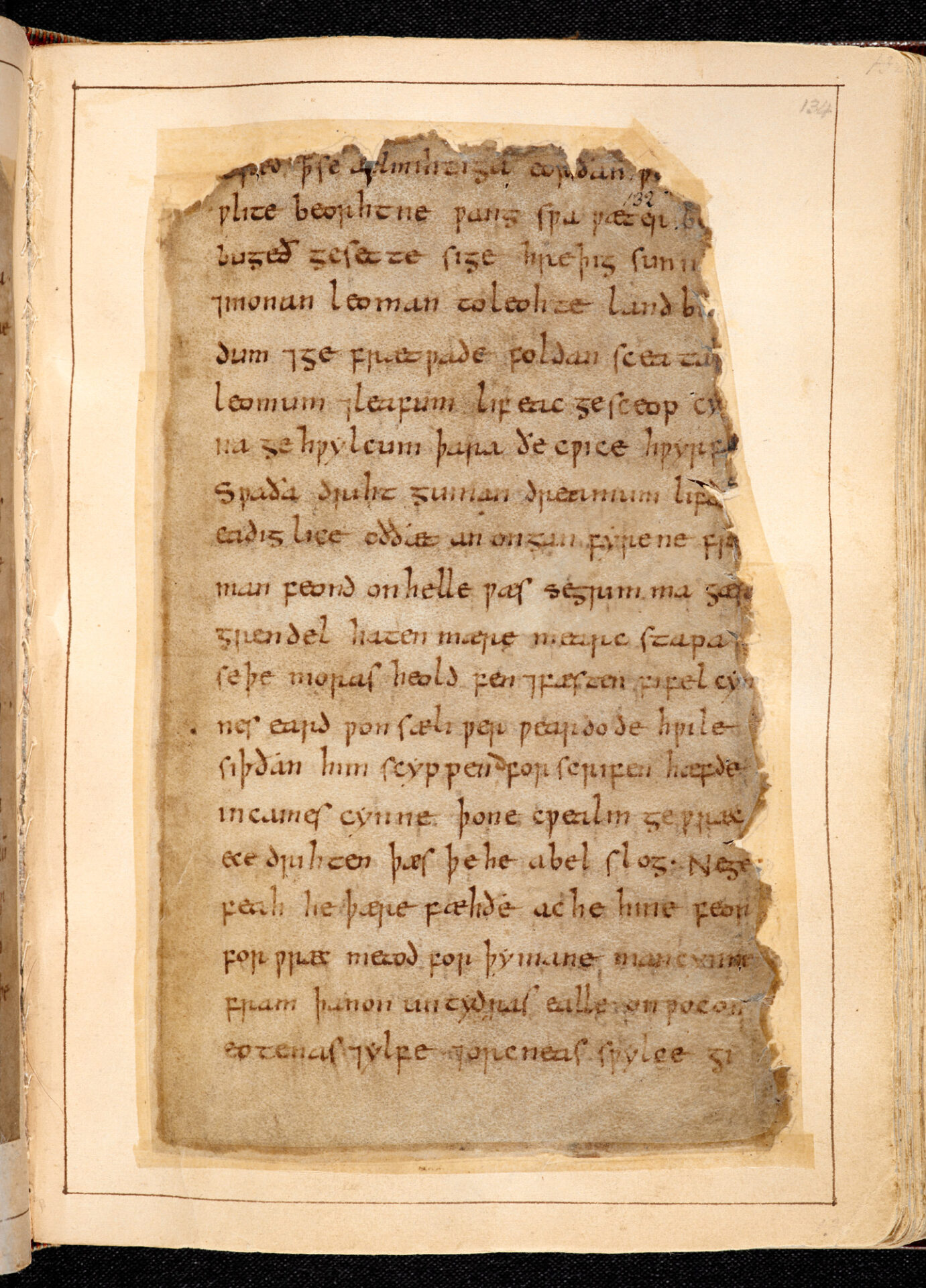

Tolkien argued in “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” (1936) that Beowulf should be seen as a work of art, a poem rather than merely Anglo-Saxon history. He claimed the monsters were the centerpiece. The poem is about our human struggle with evil. Beowulf is about a courageous good king, who like each of us is a mere human. For all his good deeds, he, like Solomon, will die on his mound of gold. For every Grendel that is put to death, another son of Cain arises to slay his kin. “For the monsters do not depart, whether the gods go or come. A Christian was (and is) like his forefathers hemmed in a hostile world” says Tolkien. “A hostile world” is precisely the motif that Reznor used on stage to visualize “Hurt.” The Middle Ages were nothing, if not filled with the same hillbilly-ness found in both Reznor and Cash’s version of the song.

The song had dark origins. In the early 90’s Reznor rented a house in L.A.’s Benedict Canyon that had once been owned by actor Sharon Tate and was the scene of her gruesome murder along with the baby in her womb in 1969 by the Manson family. It was there that “Hurt” was conceived. The Monsters that entered the mead hall at Benedict Canyon that night were more evil than Beowulf’s Grendel. Monsters can be like that—without heroes, they grow. It was no wonder that the young industrial grunge rocker envisioned a world covered in dung.

The paradoxical union of Reznor in public while on tour in 1995, drenched in a symbolic “crown of sh*t” and Cash in the privacy of his Tennessee home in 2002 envisioning a savior in a “crown of thorns” turns out to be surprisingly synergistic. One exterior, the other interior. In Reznor’s live performance, he is a prince, a death-wished lost boy in the throes of self-harm and heroin addiction. Depicted in quick flashes on the screen above and behind him are a serpent and a thorn-crowned Christ. Reznor’s world is doom-struck with environmental concerns, natural disasters, and war. In the cover version, the aged Cash is a bard with stringed instrument, a diseased and dying king at his table of plenty. His doom is of a personal nature. Reznor pointed “out there,” where most young people focus blame. Cash, in the wisdom of age, pointed “in here,” taking responsibility for his failures.

Though opposite, they are both part of one spectrum: Reznor is a young man using a needle to kill the monsters of psychological pain; Cash is an old man relying on a needle to relieve the ravages of physical pain. Reznor is at the beginning of a life he views as not worth living; Cash is at the end of a life that still is not worth much. Together, they create a piece of art that transcends the pain of this world (at both ends) while not avoiding the inevitable. Tolkien believed the theme of Beowulf to be “each man and all men, and all their works shall die” Cash envisioned his version of “Hurt” to follow the same theme.

Cash opens his video sitting at a banquet feast alone. He is surrounded with reminders of the good life that is now past. His mother is dead, his friends are gone, even June, who looks on from the staircase, will die in a few short months. His younger self disappears around the back of the house in Dyess, Arkansas. “Poof” he gestures with his hands…life is vanity. But the older, sicker, sadder Cash—he’s “still here.” His life is poured out like wine, and his legacy is gone. The shelves are empty, the awards broken, the museum is now “closed.” He is left with his “empire of dirt” while he wears his “crown of thorns, upon his liar’s chair / full of broken thoughts he cannot repair.” And if you are thinking for a moment about emulating him, then “get the hell out of here” we hear him say—and these are his own words.

Cash may as well be situated in an Anglo-Saxon mead hall, a broken ring-giver, a pagan, who for all his good intentions, cannot heal that which infects his people and himself. The hero Beowulf is in no better condition. All his honorable deeds—his courage; his refusal to accept glory; his heroic fight as an aged man; the wealth he leaves behind for his nation—is ultimately insufficient. In the end, his people will be overrun by a stronger nation and the kin-slaying begins all over again. Beowulf, Cash, and Reznor are mortal, broken, sinful men who cannot save. They cannot suffer enough for you or themselves; as Reznor writes, for they are “liars” just like you. Do not look to them for answers, they will “let you down in the end” and “make you hurt.” After all, Beowulf fought the dragon and won the gold which became a magnet that made his people “hurt” as soon as the Swedes arrived.

Though Cash only changed one word in Reznor’s lyrics, it was the visual representation, or the story Cash told that gave Reznor’s words a completely new interpretation. Cash’s Christian worldview found new meaning in Reznor’s “crown of sh*#.” In a radio interview, Reznor relates how when he first heard Cash’s new version, he dismissed it (earlier interviews were not as kind about it). But when he saw the video, it deeply moved him. He was taken back to the “personal, intimate” words “written small in a journal” that were now “juxtaposed” against the large life of this icon. No longer was Cash a usurper or invader; he was a welcome interpreter of that life.

Cash’s revision of “Hurt” won best music video of the year at the Country Music Awards (2003) and best short film video at the Grammy’s (2004), as well as best music video of all time in Great Britian (2011). A simple YouTube or Google search will demonstrate just how relevant and talked about this video still is after all these years. For Cash, it is a prophetic warning about mortality; a man who once had everything this world can give, now faces down death. Cash died seven months after making the video. For Reznor, Cash caught the transcendent quality, the art of his words, something Reznor failed to do alone. After watching the video, he stated:

I wasn’t prepared for what I saw. What I had written in my diary was now superimposed on the life of this icon and sung so beautifully and emotionally…Goosebumps up [my] spine. It really made sense. I thought: ‘What a powerful piece of art.’ I never got to meet Johnny, but I’m happy I contributed in the way I did. It wasn’t my song anymore.

Beowulf was written by Christian monks using the residue of pagan “broken thoughts” they could not “repair” with all the weregild (man price) in the kingdom. This was Cash’s point. Both Beowulf and “Hurt” end with seemingly no answers to the existential crisis. So much pain and suffering in this world and then death. Not just pain coming “at us” but the hurt we put on one another. For “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 1:9). High art belongs to yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The poetry of all three (although we do not know the authors of Beowulf, scholars believe it was a collaboration made from materials of the past) hillbilly pagan philosopher kings rise to this status.

Representing the state of Arkansas, a statue of Cash is scheduled to be installed in the U.S. Capital’s National Statutory Hall in late September of this year. Standing eight feet tall, Cash holds a Bible in his right hand. A guitar is slung over his back, headstock down. The strap drapes his body passing underneath the weathered leather-bound book. His left hand rises to meet it midway around the heart. His head is bowed in a contemplative mode. He wears the ruffled shirt of the entertainer and the long suit coat of the itinerant preacher. His right leg slightly bent in a standing kneel repose. His head is bare, there is no crown to signify royalty. His feet are covered in Western boots, and they are beautifully Gospel-bringing. Our Hillbilly King was more than a poor boy done good from Dyess, Arkansas. He was a philosopher, poet, and he might prefer the humblest epithet of them all —pagan. Fitting for the “Man in Black.”

Trent Reznor, as the “Dark Wizard of Movie Music” — is the GQ Global Creativity Awards cover star for 2024, along with his Nine Inch Nails partner Atticus Ross. The winner of multiple Grammys and two Oscars, he and Ross started a new company built around storytelling. Like Cash, he is a man comfortable in black. Writing “organically” is a “therapy session” where Reznor claims he is “the most in touch with God and fulfilled.” He lives for those moments when his words take on a life of their own, coming from somewhere familiar, but not known. Befitting a wizard (or a priest), Reznor is featured in GQ in both a black robe and a black suit. He jokes that he is a “quart low” on whatever it is that makes people happy. Apparent from an early age, the journal entries that eventually became the lyrics for “Hurt” represent honest wounds from a young man who felt the weight of the world. Groping in existential angst, he needed a fellow dark traveler.

Image via Wikimedia Commons