Soon after I started reading Sabrina B. Little’s The Examined Run: Why Good People Make Better Runners, I began searching for a jogger stroller on Facebook Marketplace. In the first year following my daughter’s birth, I ran a handful of times in the morning before she woke up for the day. But I eventually settled into a routine where I would grade, answer emails, and accomplish other work-related tasks in that brief pocket of time when I could be assured of few interruptions. I concluded that, given my current commitments, I didn’t have space in my life to run.

Then I read Little’s book, which made me long to run again. She describes the profound goods and pleasures of distance running with precision and affection, in a way that makes obvious her love for the sport and its role in her own spiritual formation. I found her stories of courage and perseverance alluring. I resonated with statements like, “nothing makes a person question their emotional maturity quite like a long run,” and “the difficulty of a task is part of what makes the outcome worthwhile to us.” Little’s passion for running is infectious. To wit, I bought a jogger stroller.

From her vantage point as a philosophy professor and an experienced trail and ultramarathon runner, Little explores ways that distance running and virtue ethics complement one another. She explains, “virtue ethics has a tradition of inquiry about flourishing and suffering that I have been both chastised by, and found solace in, during my time as an athlete.” Informed by an Aristotelian flavor of virtue ethics, Little devotes chapters to “performance-enhancing virtues” (such as resilience, joy, perseverance, and humor) and “performance-enhancing vices” (pride, intransigence, envy, and selfishness). In the latter chapter, she recognizes toxic aspects of sports culture and applies some of her insights to American culture in general. For instance, she acknowledges that greediness is a sign of poor character that nevertheless results in achievements largely considered successes in our culture, such as big houses and extravagant vacations. Similarly, in sports, Little points to certain vices, or “defects of character, which help one to be a successful athlete but can otherwise detract from a well-ordered, flourishing life.” She adds, “sometimes high-performance traits can be antagonistic toward the goods of community.”

Little provides several stories from her coaching experience, and the challenges she has faced as an athlete, that illustrate the virtues and vices she argues are relevant to long-distance running. She describes a course of cow fields that flooded during a 50-mile race and how humor helped her to move forward at a particularly low point. She states that her ability to laugh “was a performance-enhancing virtue, without which I might have despaired.” In her discussion of intransigence, she questions popular attitudes and practices among distance runners, such as their glib acceptance of the concept “death before DNF” (Did Not Finish) and the “run streak,” which is running every day for months or even years. Although holding to “death before DNF” as a guide for a race and keeping up a run streak may improve one’s performance or bragging rights, Little wonders if they are instances of intransigence that will eventually detract from one’s long-term health or relationships. Finally, a story from her coaching demonstrates how performing well can be at odds with good character. At a state championship meet, one of Little’s students assisted a runner who had fallen during the race, an act that cost the team the honor of placing. When this happened, Little reflects, “I had to check my heart,” and concludes, “this was a situation in which performance goals and character goals were opposed. Being a good person was detrimental to placing well.”

Through The Examined Run, Little consistently engages ultimate questions via the practices of a distance runner. For example, she discusses three definitions of happiness (hedonic, desire-satisfaction, and the Greek concept eudaimonia) and argues that eudaimonia is the “most promising,” given that it “helps us to understand the place of both virtue and suffering in a good life.” She points out what is obvious to distance runners but should be stated explicitly and applied to other areas of life: pain and discomfort are often necessary for achieving greater goods. She argues, “some of the hardest … moments in our lives are also the most meaningful,” such as “parenting, completing difficult projects at work, climbing mountains, and restoring broken relationships.” In her related discussion of freedom, she argues against a commonly held assumption in American culture—that true freedom is lacking restrictions to do what we want, as long as what we want doesn’t involve hurting others. As she takes issue with this definition, Little quotes the marathon world-record holder, Eliud Kipchoge, who pointedly says, “only the disciplined ones in life are free.” Little demonstrates that we are not free if we are slaves to our vices, and that our vices (or our lack of virtues) can prevent us from becoming who we want to be or from doing the good things we want to do with our lives. She explains, “our freedom is, paradoxically, formed through the imposition of disciplines … for the sake of being free in a fuller, long-term sense.” The distance runner, then, is an apt example of a free person, because she can restrict and discipline herself in order to achieve or realize greater goods.

As she engages ultimate questions about human life, Little models the pursuit of virtue and the concomitant wrestling with vice involved in this pursuit. For instance, in her discussion of human limitations, in which she debunks popular sports slogans about “limitlessness,” she wonders what it looks like to subject her training and goals as an athlete to her responsibilities to her family and students. She writes, “I am learning how to broaden the ways I measure success. My miles can be beautiful even if not maximally fast. I can run with integrity and fullness in the stage of life I am currently in, rather than begrudging myself for failing to meet performance standards that made more sense when I had fewer obligations.” It is quite ironic that this book touts the virtues of observing one’s limits, given that I can think of few sports so extreme as running 152 miles in a single race, which Little has done. Nevertheless, she grapples with common questions that are central to living a moral life and shows how distance running is well-situated to help us ask those questions and to put virtues into practice throughout our lives.

It is the author’s musings regarding her own limits, her struggles to order her loves properly, that I found most compelling about the book. Although I am a very different kind of runner (I have not run more than 10 continuous miles since high school), I identify with her efforts—as I’m sure many other readers do—to challenge herself, to test her limits, to experience the joy of accomplishing something difficult while also acknowledging that some achievements or goals have too high a cost and are not worth certain sacrifices.

As I read Little’s book and began running with my daughter in a jogger stroller, I have gladly exceeded what I thought were my limits—incorporating running into my life while I work full-time and parent a toddler. This achievement, however, has required me to think through my priorities, commitments, and limitations. Since I did not want to concede my work time to running, and I did not want to lose time with my daughter to run, I concluded that I should designate running as an activity that we could do together. It has been a great joy to run with my daughter—more joyful than I expected—but it has still required sacrifices. Running up a hill while pushing a stroller, for example, is difficult. I need to respond, breathlessly, when my daughter points out the airplane overhead or the bunny hopping through a neighbor’s yard. One day, she held up her finger and asked me to kiss the scrape there from yesterday’s mishaps. I have to stop running completely, albeit briefly, to refill her yogurt bites. Although talking to my daughter and feeding her snacks while I run is delightful in its own way, it makes for a very different experience compared to my child-free running days, when I considered it a contemplative activity. Little’s thoughtful and complex exploration of ultimate questions, especially those that involve observing one’s limits and ordering one’s loves, helped me to work through the particulars of these questions in my own life and arrive at conclusions that have made me happier and enriched my life. Running with my daughter is enhancing my freedom.

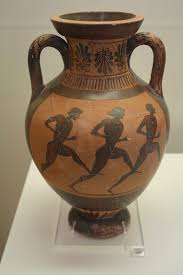

The Examined Run is a book that runners, athletes, and coaches will enjoy as well as readers interested in virtue ethics and character education. Both explicitly and implicitly, Little reminds us that one of the oldest philosophies of education, articulated in Plato’s Republic, is that we need to discipline both our bodies and minds in order to live fully. For the ancient Greeks, she explains, athletic training develops “spiritedness” while “poetry softens and humanizes.” Though her book is a philosophical argument, it is imbued with images of physical feats, descriptions of burning muscles and lungs, and celebrations of camaraderie among athletes. It will make you want to go for a run and read Aristotle, which is part of the point. The exercise of both our bodies and minds in virtuous practice is an essential aspect of attaining a good life. In a culture wherein sports is often seen as entertainment, an example of vanity, a ticket to popularity and success, or otherwise irrelevant to the cultivation of virtue or the life of the mind, Little proves that this is an impoverished perspective. On the contrary, if you want to be a better person, try going for a run.

Image via World History Encyclopedia