We tend to think of gossip as a negative or even sinful activity. Reality stars screaming at each other. Angry memes. Twitter wars. Socialites. Celebrities. Fluff. Meanness. The origin of the word gossip, however, is quite different: gossip is derived from the word godsib, first spoken in AD 1014, as a mixture of the words god and sibling. Basically, the original idea of gossip formed around the concept of a godmother or godfather, or one who formed a spiritual relation with someone else—a god sibling. God sibling became gossip. Gossip eventually came to mean a close friend, then, with whom one shared a spiritual bond, a friend as close as family and one whose closeness was known to have historically been tethered through that sacramental act of baptism where one made a covenant with God to look after that other person. Eventually, gossip came to be known as the performative act indicating friendship, or the conversational practices occurring between friends. Gossip, therefore, forms the ecology of friendship, if you will. Specifically, it is the bond denoting a unique friendship, its special relationship with God indicating even moral conversation and relationship, a far cry from what we think of when we consider gossip today.

In the mid-nineteenth century (and earlier), the idea of gossip was not seen as intrinsically negative in the vein we know of it now but was still in an evolutionary phase grounded in positivity. That is, it was seen as a good that, like anything taken to excess, could become evil if not performed in a spiritually sound manner. Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women provides an excellent touchstone for this topic because there is perhaps no better book known for its idealization of friendship and family, bounded together via gossip, where young people learn how to socialize well with each other while modeling adult conversational practices. Indeed, the conversations that happen in Little Women among friends, including between the March sisters and between Acott and her audience, become a training ground for what I consider to be “good gossip.” I define this “good gossip” as occurring when moral codes are learned: it is God’s language that connects friends together and creates bonds that are simultaneously long lasting and spiritually fruitful.

The first chapter of book two of Little Women is aptly titled, “Gossip.” Between the publication of books one and two, actual gossip about Alcott and her characters abounded. After all, the somewhat unexpected, instant success of book one can be attributed to, as scholar Anna South writes, Alcott’s “richly imaginative and visually lively characterization,” a characterization that makes readers feel as if they are “saying farewell to old friends” at the end of book one.[1] In the interim between books one and two, Alcott famously receives letters from readers gossiping about her characters and what she ought to do with them next. It is no accident that Alcott addresses her readers directly, then, at the beginning of book two, in a chapter titled “Gossip.” She commences book two’s narrative in this way, writing: “In order that we may start afresh and go to Meg’s wedding with free minds, it will be well to begin with a little gossip about the Marches. And here let me premise that if the elders think there is too much ‘lovering’ in the story, as I fear they may (I’m not afraid the young folks will make that objection), I can only say with Mrs. March, ‘What can you expect when I have four gay girls in the house, and a dashing young neighbor over the way?” (307). Note, here, that Alcott is unafraid to “begin with a little gossip,” hailing her audience as friends, as those interested in the happenings of the March sisters. Indeed, what she does in these first few sentences is quite layered, when one reads it closely. “Gossip” is what will help her readers go into Meg’s wedding with a “fresh mind.” It is cleansing.

“Gossip” is an invitation to moral conversation. As a friendly narrative guide, almost a maternal one herself like Marmee whom she likens herself to, Alcott uses gossip to dissuade readers from any ill-conceived conceptions they may have had from the previous book. These are the stories you need to know about the characters, she says, and this is how you should interpret them. As an omniscient narrator, but one who inserts herself into the story, it is possible to argue that she acts as a “godparent of sorts” for her readers, who have become her friends and her characters’ friends, using gossip to direct readers as to how the narrative, both past and future, should be interpreted. That is, she is the reader’s “god-sibling,” offering her audience gossip about the Marches, but she does so with love—and tells them not to consider what’s been told before in a negative light, such as “too much lovering,” for instance.

Alcott embraces this gossip as a mode of spiritual practice, doing so purposefully because gossip, moralizing talk of the everyday and commonplace, is part and parcel of daily existence, both in Alcott’s time and ours. Evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar, for instance, has ascertained that social topics, such as personal relationships, likes and dislikes, anecdotes about social activities—make up about two-thirds of all conversations in human relationships. This holds steady through time and marks how humans have created and maintain social communities. The one-third of humans’ time not spent talking about other people in their local circle or themselves is devoted to discussing everything else: sports, music, books, politics, etc. In other words, most of our conversational lives as humans is spent gossiping, telling stories about those close to us within our circles, our family and friends. Dunbar’s evolutional theory is that as humans became fruitful and multiplied, they began to live in larger groups, and it became hard to keep track of what everybody was up to just by observing them. And so we needed language. Language allows us to know what other people have been doing, even if we weren’t or aren’t there to witness it. Stated simply, when a person chooses to share a story about someone else, it’s because they think that story is significant in some way. Gossip is functionary, then, but it also helps us learn how to live our lives in relationship with one another and to connect with those who we may not know enough about or who we may miss.

To reiterate: this relational guidance is exactly what happens between books one and two of Little Women when readers are not with the March family for a while and then return to that chapter titled “Gossip.” Alcott tells readers in that chapter what she thinks is significant in the time that has passed between books one and two and how those events and stories ought to be interpreted. “The three years that have passed have brought but few changes to the quiet family,” she shares. “The war is over, and Mr. March safely at home, busy with his books and his small parish which found in him a minister by nature as by grace—a quiet, studious man, rich in wisdom that is better than learning.” As she continues, Alcott extolls how Mr. March lives and explains how her readers should perceive him. She wants her readers to learn from this story, to feel as if they are a part of this ecology of friendship and shared familial, Christian kinship that she is creating through her novel.

When hearing about gossip, today, we might automatically expect to hear of yet another salacious political scandal or to be thrilled in some way by a favorite celebrity’s splashy beach resort wedding and then not-so-surprising Instagram “conscious uncoupling” announcement a few weeks later. You might consider here any popular social media or news outlet to consider how much of this sort of gossip they feature (yes, even your favorite). By contrast, Alcott tells readers that this family is “quiet” and “ordinary,” and that this everyday activity, this everyday “quiet” life is worthy of extensive storytelling. This is what readers have been waiting for! “Earnest young men found the gray-headed scholar as young at heart as they!” she divulges,” and “Sinners told their sins to the pure-hearted old man and were both rebuked and saved!” These sentences are punctuated with exclamation marks. The drama! The intrigue! These are her opening bits of gossip about the March family to her readers. Their local, everyday morality matters: this is exciting news worth telling. Worth exclaiming!

Contemporary psychologists have suggested that when we seek out gossip and find those perhaps less moralizing stories expected in Alcott’s chapter titled “Gossip,” there remains a moralizing frame. In a Review of General Psychology article about gossip, the authors write that even in classic cases of what I would call “bad gossip,” “the defamation of the target’s character is not the primary goal, and may even be irrelevant. A piece of gossip, instead, is an opportunity to find out how someone did something right, or something wrong, and learn from the example. Learning how to live with others is something that continues throughout life—once you’ve learned not to eat paste, for example, you can graduate to more nuanced lessons of human behavior.”[2] Gossip, again, is both evolutionary and morally functionary in society.

Now I do not suggest one must always speak of well someone to participate in “good gossip,” nor does Alcott always tell flattering stories about every character. They are not all Mr. Marches in Little Women. The author does not shy away from being blunt about certain character’s failings and their complexities, which makes the characters feel more like real friends to her audience and worthy of “good gossip.”

Indeed, we learn in this same gossip chapter that “old” Aunt March bribes Amy to stay with her, choosing Amy over Jo as a companion. From their past relationships, astute readers of the novel perceive that Alcott is characterizing Amy as a little selfish, Jo as a little strongheaded, and Aunt March as a little difficult and prim—and I am using rather scaled back gossipy language for all of these characterizations.

Yet as good friends of the characters, as Alcott wants us to be, we like the characters despite their flaws, and though we may talk about those flaws, we know that we and the characters ought to learn from them. We should all grow better from relationship, from communion with each other. Thus, in a swift turn of phrase about a change of situation (Amy’s change to being Aunt March’s companion) Alcott has her entire readership participating in gossip that is moralizing and true, yet not necessarily overly didactic. Gossip moralizes without preaching. It is, when used well, a form of God’s friendly conversation. Having said this, we all know we should aspire to be more like Mr. March, which is why he has those long paragraphs of virtuous description about him at the beginning, and this other remark is an offhanded remark. Yet both are gossip. Both are accomplishing their moral function in the stories.

In the end, we gossip to learn about how we ought to act and think about the world. There are good and bad ways to gossip, to converse about each other with each other. Just as training wheels help us find our balance before riding a bike on our own, we use conversations about each other’s behavior to gauge the reactions of others, allowing us to test the moral waters with others we trust before we commit to, or even fully understand, our stance. We also use these conversations to guide others in ways that are enlightening. We may claim it is uniformly bad to talk of someone without them there, to speak of them “secretly,” but to do so publicly, and early, would be to make moral pronouncements not fully formed quite yet. Think of cancel culture gone awry. A good friend, a god sibling, or “a good gossiper,” as this piece argues, will help you parse out the good ideas you might have of others from the bad, while a protecting your moral nature, your ability to discern, and the dignity of the person being discussed.

We are all flawed. To acknowledge ours and others’ flaws isn’t bad. To ostracize others because of what we perceive as their flaws, especially if we haven’t discussed them thoughtfully and acknowledged our own, misses opportunities for growth, personally and collectively. To love and learn from each other in our communities is what good gossiping accomplishes. At the end of Little Women, Marmee holds out her hands with joy as she “gathers her children and grandchildren to herself, with a face and voice of full of motherly love and humility—Oh, my girls, however long you may life, I never can wish you a greater happiness than this,” she pronounces. This is the final outcome of the good gossiper, and perhaps of a narrator and author like Alcott who still, today, gossips with her family of readers, and their children and grandchildren, exceptionally well, leading them all to be a little more virtuous.

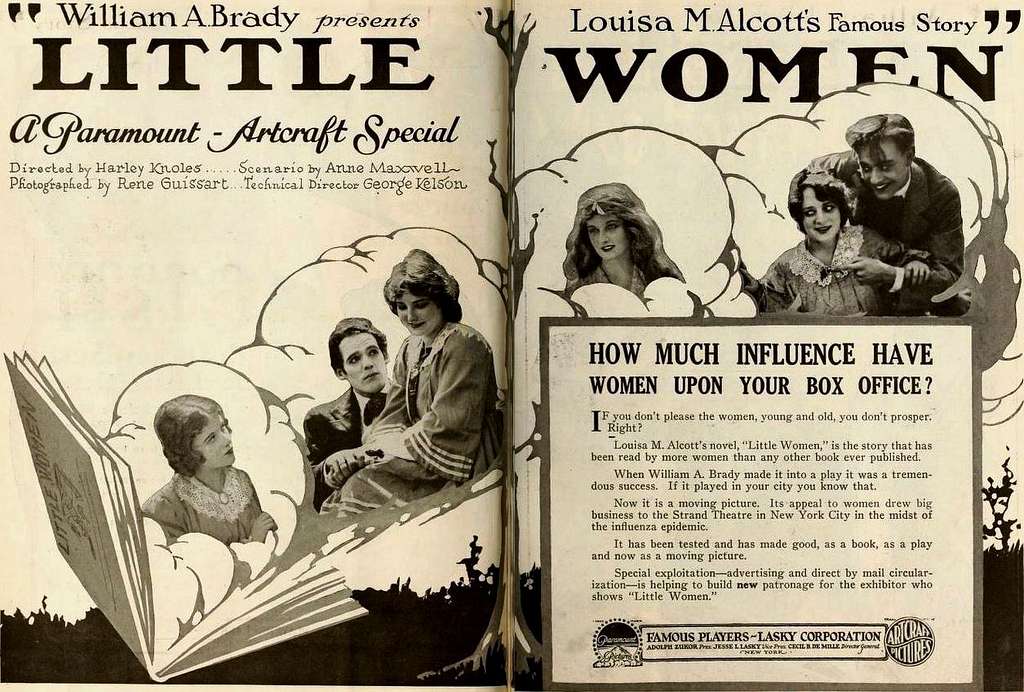

Image via Picryl

1 comment

Keturah Hickman

I love this, and love how you tied it to Little Women. Wrote something similar on the necessity of ‘sanctified’ gossip a few months back for my substack. I think that the Salem Witch trials are in part to blame for the belief that all gossip is slander. It’s still a healthy part of Amish lifestyle though, and I’m glad to see it’s making a comeback in regular Christian circles.

Comments are closed.