“Community” is all the rage these days. We need community events, community sponsorships, community building, community groups, community boards, community everything. People seem to be in agreement that communal bonds are good, and that they need to be built. I am sure I am not alone in wagering that this hunger for community has something to do with the pandemic. Everyone was cooped up and could not see their friends or family. In that sort of environment, where making new friends felt like a pipe dream, it is no wonder people were itching to build some community. Clearly that is a good thing. People need relationships, and you cannot have relationships without spending time with people, so I’m encouraged by this trend.

But it also worries me. First, saying a word over and over and over again can drain it of its meaning. If everything is community, then we fail to really identify what it means to have strong communal bonds. The second worry, and the thing I want to focus on here, is that a lot of these activities are sponsored by some organization. Whether it’s a nonprofit, a church, a town government, a business, or something else, these community ordeals are put on by some official organizer. A church organizes a community engagement event, an arts center organizes a community art show, a town government organizes a community festival, a business organizes a community mixer. These are all good things. They help us meet new people and interact with people we might not otherwise. Learning to go outside of our immediate relational web is crucial, particularly in how it prepares our imaginations to engage with people outside of our ideological, theological, political, or practical spheres. But my worry is we will begin to think of these activities as the answer to our lack of strong relationships: I feel lonely, so I will go to a community event. I get my fix and return home until I feel lonely again. Community can then become a function, responsibility, and mandate of broader organizations. Organizations—like churches and governments and civic groups—can help build community. But we cannot trust institutions with our relational needs. As Wendell Berry’s short story “Fidelity” helps us consider, cultivating strong, loving relationships requires moving beyond organizations that should not, because they cannot, do our work for us.

“Fidelity” engages with one of these organizations: the law. One of the primary characters, of this story and of Berry’s fictional town Port William, is Wheeler Catlett. He and his son Henry are confronted by a sort of organization that aims to regulate the relationships of this community. More specifically, an agent of the law named Detective Kyle Bode attempts to regulate the relationship between Burley Coulter and his formerly illegitimate son, Danny Branch.

The story takes place in Burley’s last days when his community gathers to care for him. When they initially realize he is close to the end, his closest family—his son Danny Branch, his daughter-in-law Lyda Branch, his nephew Nathan Coulter, and Nathan’s wife Hannah—take him to the hospital. The doctors confidently promised to heal Burley, and even when he “slipped away toward death… the people of the hospital did not call it dying; they called it a coma. They spoke of curing him. They spoke of his recovery” (“Fidelity,” That Distant Land, 112). But Burley was disoriented in that place. He was not himself. Lyda joins in the sentiments of Burley’s loved ones: “Like the others, once they had given him into the power of the doctors and into the sterile, hard light of that way and place in which he did not belong, she had wanted him back” (156). Danny decides to sneak Burley out of the sterile lights of the hospital and into the night. This begins an eighty-page conflict between their close-knit love for each other and the assumptions and interests of the law. At the heart of this conflict are two characters: Detective Kyle Bode and Wheeler Catlett.

Detective Bode enters the story as an outsider, whose assumptions will be challenged by the community he encounters. The peculiar case of a disappearing hospital patient takes him to the “godforsaken hills and hollows” that “offended his sense of the way things ought to be” (145). Early on, as he grew up in Lexington, his professional—and even vocational—goals aspired toward clarity and order. As he gets into his life as a detective, he clings to legal frameworks as a source of that order he desires. Meanwhile, paradoxically, his personal life reflects a steadfast commitment to liberation, devoid of relational accountability. He is liberated from the bonds of two marriages, leading to dissatisfaction at the hands of freedom. Left to the loneliness of an unaccountable personal lifestyle, he turns to his career as an arena to impose order upon other people. An organization fills a relational hole. Or so he hopes.

Bode’s dissatisfied liberation is contrasted with the relational commitment that Wheeler and Burley have to each other and to their community. Wheeler Catlett works as a lawyer in the town of Hargrave. He had studied law at a university before getting the opportunity to work in Washington D.C. But he returned to Hargrave, Port William’s neighboring town, to represent people he knew, eventually working alongside his son Henry Catlett. Wheeler has a history of harnessing his position as lawyer to defend the interests and needs of his community. As James Decker illuminates, he defends friends such as Burley not primarily as paying clients, but as friends. Like Detective Bode, Wheeler works in the legal field and considers the law as a means to attain order. However, in “Fidelity,” he chooses to prioritize the well-being of his friend Burley over the dictates of the law. In resisting Detective Bode’s legal sensibilities, Wheeler Catlett and his son Henry shift the responsibility of handling relational accountability away from the law. The Catlett response to Bode will expose the anthropological assumptions undergirding Bode’s misplaced trust in the organization of the law to regulate relationships.

When Detective Bode first enters the law office, his loyalty to the “organization of the world” is challenged by Henry Catlett’s loyalty to his neighbors. After meeting Henry, Detective Bode begins with a line of questioning concerning Danny Branch as a possible suspect for the kidnapping of Burley Coulter. In response to Henry’s evasion, Detective Bode attempts to gain some solidarity: “The detective made his tone more reasonable, presuming somewhat upon his and Henry’s brotherhood in the law: ‘Mr. Catlett, I’d like to be assured of your cooperation in this case. After all, it will be in your client’s best interest to keep this from going as far as it may go’” (164). After Henry says, “Can’t help you,” Bode demands of Henry a loyalty to the law: “You mean that you, a lawyer, won’t cooperate with the law of the state in the solution of a crime?’” (164). Bode’s question is a valid one. But Henry considers his role as a lawyer to be subordinate to other obligations and relationships. Henry says it is a matter of patriotism, which he defines as “love for your country and your neighbors” (164). Their lived-in country, as opposed to the state and other organizations, is what Henry represents.

Henry further indicts Bode’s organizational allegiance: “You’re here to represent the right of the state and other large organizations to decide for us and come between us” (165). Henry refuses to accept that the state can make decisions for him and his neighbors. While Bode accuses him of anarchism, Henry’s true motivation is found in a concern for the people around him. He wants to be able to perpetuate the connections between him and his friends and family—quite the opposite of lawless chaos. Henry asserts the reason for his opposition to Bode’s intentions: he does not want anything “to come between us” (165). Henry opposes Bode’s understanding of the law as a means to decide people’s actions at the expense of their life together. Contrary to Bode’s motivation of control runs Henry’s motivation of togetherness. Henry says, “‘What I stand for can’t survive in the world you’re helping to make, Mr. Bode.’” Henry and Wheeler represent something more important than the law: their neighbors (165). Here Henry demonstrates that his goal in lawyering is to secure the good of his neighbors. As Richard Church recognizes in Henry and Wheeler,

The title lawyer is borne by Wheeler and Henry only insofar as the law continues to serve these higher goods, and they obey the law only insofar as ‘law expresses love of neighbor.’ Thus, when the law comes not in service of their neighbors, Wheeler and Henry walk outside its confines into the dark world that they have been called to serve. (“Of the Good That Has Been Possible in This World: Lawyering in Port William,” Wendell Berry and Religion: Heaven’s Earthly Life, 61)

Church’s point here is crucial. A right relationship to the law, and other organizations like it, depends upon a correct understanding of purpose and priority. For the Catletts, the law’s purpose is to help love and serve neighbors. So if the law and love for neighbor get in each other’s way, love for neighbor should always win out. For Wheeler and Henry, then, serving neighbors always takes priority. They are willing to walk outside of the enlightened knowledge of the organization of the world to do so. We should similarly prioritize love for neighbor over the law because we recognize the law’s limits in fostering relationships. It is incapable of fostering personal relationships because it is primarily concerned with regulating action and separating people (in Henry’s words, “to decide for us and come between us”). The Catletts demonstrate that the law does not always best serve relationships. So it is with any organization.

Without law as a steadfast authority, the fear arises that a person would then be free to act however they please. But Wheeler Catlett’s interaction with Detective Bode offers an alternative model of accountability. After meeting Wheeler, Bode implicitly accuses Danny of acting out of personal interest. Bode assumes that, without the parameters of the law, Danny would pursue his own monetary gain at the expense of Burley. Wheeler responds,

I don’t doubt that Danny, assuming he is the guilty party, has considered the cost; he’s an intelligent man. Even so, I venture to say to you that you’re wrong about him, insofar as you suspect him of acting out of greed. I’ll give you two reasons that you had better consider. In the first place, he loves Burley. In the second place, he’s not alone, and he knows it. (174)

Wheeler admits that Danny is likely aware of the monetary dynamics of the situation. But he also gives two reasons why Danny would not act out of selfish motives. Danny’s love for Burley means that he would not take advantage of him. While Wheeler does not elaborate, his use of this as a reason suggests that love requires some sort of commitment to a person. In this case, Danny is more concerned with taking care of Burley than his own individual gain. If he were to greedily bring Burley to his death, that would clearly be unloving. In order for Danny to love Burley, he must value him above his own personal interest.

Wheeler’s second reason is that Danny is not alone. This reason critiques Bode’s legal assumptions and points to relational, rather than legal, accountability. He expands on that claim: “He’s not alone, and he knows it. You’re thinking of a world in which legatee stands all alone, facing legator who has now become a mere obstruction between legatee and legacy” (174). Wheeler recognizes the assumptions behind Bode’s implication of greed. In critiquing this “world,” Wheeler (and Berry) is critiquing an assumption commonly held by people today, one rooted in the political theory of Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes’s “state of nature” is the world that many people assume when they seek their own self-interest at the expense of others. According to Bode’s state-of-nature world, Danny is an isolated “legatee” operating according to his own interest. If Danny is abiding by his personal interest, he could not help but to secure the wealth by getting rid of the only thing, Burley, between him and his “legacy.” In such a world, the law is absolutely necessary to prevent Danny from pursuing wealth at the cost of murder. Bode polices that world. Wheeler, however, suggests an alternative world:

But you have thought up the wrong world. There are several of us here who belong to Danny and to whom he belongs, and we’ll stand by him, whatever happens. Whatever happens, he and his family will have a place, and he knows it. After money, you know, we are talking about the question of ownership of people. To whom and to what does Burley Coulter belong? If, as you allege, Danny Branch has taken Burley Coulter out of the hospital, he has done it because Burley belongs to him. (174)

Danny belongs to people, and they belong to him. Wheeler describes the importance of this belonging, building on the terminology used earlier by his son Henry (166). They will stick together “whatever happens.” They will always take care of him because belonging to each other also means they are accountable to each other. This accountability is what keeps Danny from pursuing personal gain. Danny may be breaking the law, but he would not exploit his father because the people he belongs to would not allow it. Danny is not free to act however he pleases because he is accountable to those people he belongs to. This is meaningful, enriching, fulfilling relationship. And no organization can regulate or prescribe it.

In opposition to Bode’s loyalty to the law, Wheeler insists that other ideals should be prioritized. As their conversation comes to an end, Wheeler says, “Would you grant a proprietary right, or even a guardianship, to a hospital that you would not grant to a man’s own son? I would oppose that whatever the law said” (175). Wheeler’s legal knowledge evidences itself here to Detective Bode and anyone else listening. Wheeler is operating in the language of the legal world. He employs that language and the language of love he has learned from neighbors to move beyond the world of law. The logical conclusion of this movement comes by saying he would oppose the law if need be. But Bode remains loyal to the law: “‘Well anyway,’ Detective Bode said, ‘all I know is that the law has been broken, and I am here to serve the law’” (175). At last, Bode has revealed his ultimate loyalty to the law. He does what he does for the purpose of serving the law. In this case, that means ignoring the reality and needs that he finds in the people he meets. For instance, he has not listened to Wheeler’s explanation of the relation between Danny and Burley, the two central figures in his “case.” To even begin to understand the dynamics of the case, Bode would have needed to pay more attention when Wheeler told this story.

Wheeler’s commitments lead him to point beyond legal concerns, “‘But, my dear boy, you don’t eat or drink the law, or sit in the shade of it or warm yourself by it, or wear it, or have your being in it. The law exists only to serve’” (175). Bode serves the law because he assumes, or at least hopes, that the law and the order it aims toward will provide some sort of satisfaction through simplicity. But Wheeler redirects the conversation because he recognizes Bode’s foundational misunderstanding: the law does not sustain a person. By serving the law, Bode ignores those things that actually do sustain a person. Political theorist Patrick Deneen diagnoses modern life with this propensity and offers an alternative: “While modern life divorces us from our sources of sustenance, thoughtfulness by contrast undergirds life within cultures and traditions that cultivate not only our understanding of those sources but a sense of gratitude, wonder, and honor” (“Wendell Berry and the Alternative Tradition in American Political Thought,” Wendell Berry: Life and Work, 311). As Deneen suggests, Bode’s ignorance of meaningful sustenance is a common theme in modern life. Wheeler, however, insists on a thoughtfulness for the things that people need: food, water, clothing, comfort. He implicitly invites Bode to consider all of the things in his life that provide these things: plants, animals, the sun, and people.

Because people sustain each other, Wheeler points beyond the law toward the neighbors he wishes to care for. Bode elevates the law above the people of Port William. Wheeler, however, says, “The law exists only to serve… all the many things that are above it. Love” (175). Law, and any structural framework, is only valuable insofar as it serves those things above it. Wheeler illuminates the disorder of Bode’s priorities by asserting that the law should not supersede friendships between people. For a person is sustained by the people around them, not by the law.

To be clear, the Catlett accusations do not apply across the board. For instance, Henry says Bode wants knowledge to be used for power. But not all organizations relate to knowledge in that way, and not all officers of the law do so either. Law upholds a certain type of order necessary for people to interact with each other without fear of harm. The Catlett lesson is not that we should completely distrust all organizations of the world. That is because organizations can help create an environment which makes it more plausible to commit to others. Instead, the Catletts teach us to examine the organizations in our lives so we might understand their motivations and the ends they serve. We must know their place in our lives so we know all the things that are above them. As the Catletts proclaim, the law cannot give us strong, deep love for each other.

Organized community events bring people together and are an integral part of forging strong communal bonds in a place. Like the law, they serve a purpose in a community’s ecosystem of relationships. So join the community boards. Attend the community events. But all these things serve what is above them. If your spouse or child or friend asks for some time, give it. Cultivate the loving enjoyment of their presence devoid of any mention or thought of “community.” Skip that meeting because it only exists to serve everything above it. It cannot give you the love Danny has for Burley. Some organizations are aimed toward such a love. It is right and just to be part of and align ourselves with such organizations. But even those organizations cannot do the personal, daily work it takes to commit ourselves to people around us. That is a personal responsibility we receive or refuse each day.

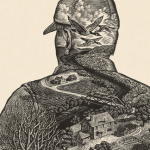

Image via Flickr