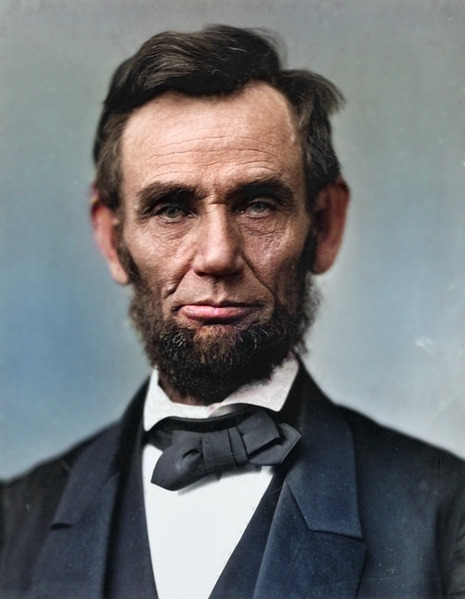

One month before the 161st anniversary of the Gettysburg Address and 248 years after the Declaration of Independence was signed, I attended a poetry reading in the Kalorama neighborhood of DC. Abraham Lincoln delivered his historic speech on November 19, 1863, placing this party squarely within those momentous weeks that build up to Halloween in Washington. My husband and I had not yet settled upon our ultimate disguise—zombie Nancy and Ronald Reagan—so, that evening, we arrived at the poetry salon straight from work, clothed as our usual corporate hacks. Others came better prepared.

Our hosts were dressed as Frog and Toad. In real life, Frog is a national security buff with flowing flaxen hair and a habit of offering her guests sips of unpasteurized milk in the kindliest midwestern way. Toad is a bank lobbyist by day and surrealist poet by night. He is also the mastermind behind these art receptions and has what I imagine to be the same quality possessed by the Duke of Choiseul and other curators of eighteenth-century literary salons: that God-given ability to assemble personalities and talents from disparate social circles to form a new yet cohesive whole.

Regular attendees of Toad’s salon fall into two camps. One includes older fixtures of DC’s alternative arts community—spoken wordsmiths or fantasy illustrators—who, while maintaining day jobs, have let their artistic passions bubble up toward the outer layers of their public personas. The rest of us are youngsters who work government or adjacent jobs and are, generally and for the most part, artistically repressed.

The evening’s featured poet, Paul Killebrew, belonged to the first camp. On this night, his black hair was saturated in fluffy mousse, as though mid-scalp scrub. He sported a terrycloth robe. Killebrew padded bare-chested and barefoot across the hardwood floors of the palatial condo until he reached the velvet throne which Frog and Toad had designated at the front of their parlor as the poet’s. Listeners gazed up at the orator from quilted floor cushions. Lit by oozing candelabras alone, the space was dim: the bard donned red spectacles and began his tale.

Time is filled / with constant sound / that occasionally / impresses itself / upon a clutter of seconds…

“Muted Flags” lasted a dreamlike twenty minutes. Unpracticed in prolonged aural reception of the arts, my mind wandered from the verses to consideration of my day and back again. I had spent the last eight hours making a video compilation of students and scholars including Diana Schaub, Allen Guelzo, and Harvey Mansfield reading the Gettysburg Address.

My intent was to collect recitations and commentary on the speech’s legacy to commemorate the upcoming anniversary. Participants approached the task with gravity, and I spent dozens of hours filming and marking timestamps on raw footage of people solemnly chanting Lincoln’s words.

Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent…

Most Americans recognize this introduction regardless of whether they realize Lincoln’s equation amounts to 1776. The more historical awareness the better, but the fact that these words from the midst of the Civil War are alive in the collective consciousness today is remarkable given the dominant narrative that Americans can’t agree over heads or tails.

We can all agree that the Gettysburg Address is a fine speech and a treasured reminder of our cultural inheritance:

…a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

I hoped to layer the recordings so that many voices would proclaim in unison Lincoln’s call to preserve the republic. From this fantasy the poet’s voice startled me, drawing my attention back into Frog and Toad’s living room. Eerily, Killebrew was describing an experience parallel to mine:

For the video / I hired five / let’s say “affordable” / actors and gave them / an incredibly / rudimentary script / of fifteen short, / unconnected statements, / which I asked / them to say / one after another / directly into / the camera / in a specific / emotional register…

When recording Gettysburg, emotional register typically came into question with the line:

But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow — this ground.

Some readers wondered, “Should I emphasize the object of the verb?” Dedicate. Consecrate. Hallow. Others, “Should I emphasize the we?” I lean toward this option because of the significance that “we” refers to us the living and to our responsibility to remember and make worthy the sacrifices of “they” whom Lincoln dubbed the brave men, living and dead, who have struggled here.

Readers who did not pause to consider the emphasis of this line tended automatically to emphasize the negation, amplifying what we cannot accomplish. I believe this stems from an internalized sense of futility toward civic action that has taken hold of many of us. With this outlook, one believes either that all great men have died or that those men once considered great have ultimately failed us. Killebrew’s poem asked and answered:

And your past? / It’s like a chronic disease / that occasionally flares up / and consumes you.

With this outlook, history seems wrought with lies and the present with so much confusion that the future looks bleak. Understandably, it’s tempting to give into absurdity when even those who seek harmony are often met with dismay. The narrator of the poem returned:

I stand watch / for exact correlations / between objects in space / and shapes, / shapes that make / tenable settings / in my eyes, / but that / seem always / just / out of sync.

With deadpan humor and unnerving insight, Killebrew’s poetry holds a mirror to this all-too-common sense that something is not right. As his verses unfolded, the parallel realities of the video editing in the poem and in my own project culminated in another cosmic coincidence when the poet invoked Lincoln himself:

I imagined each / of the actors / from my video / asking me a question / that appears in / a footnote in the Thomas Nagel / essay “Death”: / “Abraham Lincoln / was taller than / Louis XIV. / But when?”

The costumed audience rippled with mirth at the riddle. A sketch-artist disguised as a banana let off peals of laughter. As though climbing a spiral staircase of mounting absurdity, the voices and expressions of actors in the poem eventually ascended into garbled nonsense to which the narrator would submit:

What they came / up with was insane, too much / really, so / I decided to / edit the video / by taking out any recognizable speech / and cramming everything / else together… The result was / a jumpy collage / of mouth noise / and unconsummated / facial expressions, / which was incredibly tedious to edit / as I’m sure you can imagine…

Could I ever! Oh, I felt for that editor—however tedious my own edits, at least the speech I spliced was harmonious. The words rang true when first spoken and have for centuries since.

Brevity is one cause of Gettysburg’s endurance. Of its 272 words, 196 are monosyllabic. “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes,” conceded President of Harvard, Secretary of State, and headline orator Edward Everett in a letter to Lincoln the following day.

Accessibility is another of the speech’s main assets. Lincoln’s English is Mark Twain’s English. The president cut against the trend of the nineteenth-century classical orators like Everett who made frequent and explicit references to antiquity. Lincoln, too, was steeped in the classics—Gettysburg echoes Pericles’ funeral oration and even Euclidean geometry in the notion that all men are created equal is a “proposition” or something that must be proved with rigor—but his clearest references are to American founding documents and the King James Bible.

A third element which contributes to the longevity of the Address is Lincoln’s mastery of time. Not only a profound eulogy and a commentary on current affairs, his speech also assigned to the living and to indefinite future generations a responsibility:

…that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

If proving the viability of the American experiment seems like a tall order, that’s because it is. The proposition that all men are created equal is not proved in the same way a geometer proves that in right-angled triangles the square on the side opposite the right angle equals the sum of the squares on the sides containing the right angle. To prove the American proposition, we must dedicate our lives to its truth with our deeds every day, and maybe someday with our lives themselves.

Until that day, why not take after Frog and Toad? A simple step toward greater equality might be to invite over some friends, sit on the floor, and read aloud great verses.

Image via Wikimedia Commons