This essay was first delivered as a talk at the recent FPR conference in Grand Rapids.

It is terrible to contemplate how few politicians are hanged.

This perfectly civil crack about politicians slowly twisting at the gentle insistence of the breeze belongs to the civilized world by dint of its structure and cunning, neither of which I’ll go into. It is also civil for the simple reason that a very civil man wrote it. His name is G.K. Chesterton. You know he was civil and civilized because he once defined Catholicism as a thick steak, a pint of stout, and a fine cigar. This has even been known to convert a few west Michigan Dutch Calvinists to the Romish faith.

Wouldn’t it be a nice change of pace if you heard more slams from politicians themselves, not against their political enemies but against politicians in general? I get the feeling that if the governor here used Chesterton’s line, her detractors would promote her from terrible to incompetent. Back in the heyday of executive dalliance Bill Clinton, in a flash of inspiration, might have offered a variation and used the word “hung” instead of “hanged.”

Of course there is the example of Ronald Reagan. I have friends who are Lefties and are therefore obliged to despise Reagan, not because of what he did or didn’t do but because he was not a Lefty; I have friends on the Right who would sacrifice a virgin to Reagan’s memory if they could find one.

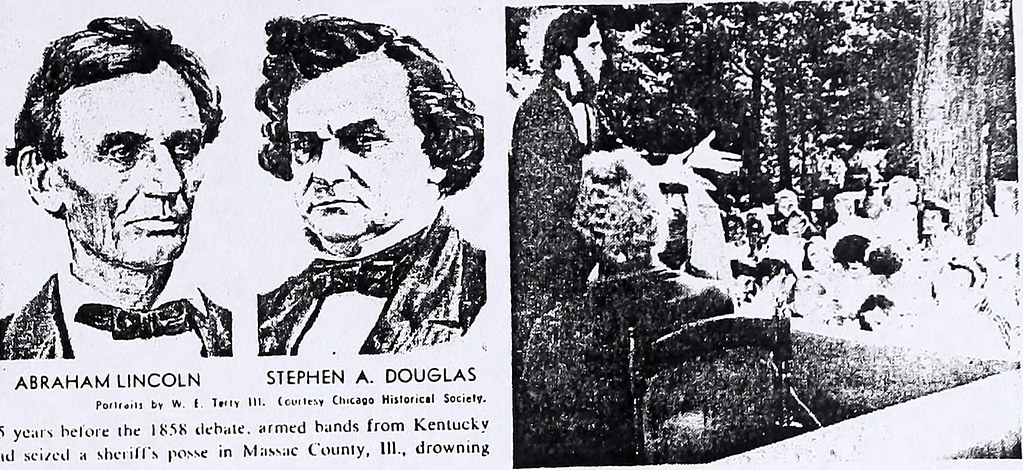

I don’t have a dog in that fight, for my concern is not with whether he or any other president was good at presidentializing. My ultimate concern here will be with what a public person of distinction looks like; my concern at the moment, before I come to that, is with the ability to speak in a way that doesn’t make your auditors pray for immediate and even painful death. Plus I’ve never been able to convince myself that presidential politics is worthy of a sane man’s attention. The Democratic and Republican national conventions have made this clear in spades: they resemble outlandish birthday parties for the kindergarteners of rich supermoms who earned degrees in beer pong. I say nothing of the made-for-TV events to which the term “debate” has been grossly misapplied. Is this what Lincoln and Douglas engaged in? No greater abuse of language has been committed since the press conference in which Kobe Bryant admitted to the “mistake” of adultery.

Your first responsibility to your fellow man and your fellow woman is to be interesting. Dull people are the reason we still talk about euthanasia. Can you imagine the current hologram in the White House ever saying, as Reagan once did, that “Government doesn’t solve problems; it subsidizes them”? Or that “Government is like a baby: an alimentary canal with a big appetite at one end and no sense of responsibility at the other”?—and that the government “will always find a need for whatever money it gets”? It’s at least funny that a chief executive would speak in this way about the thing he is the chief executive of. Maybe if you’ve been too busy your whole political career being a warmongering grifter, you won’t be able to think of a single clever thing to say—and then when senescence sets in you’ll pass the baton to someone who in the 2020 primaries fairly shattered the glass floor of popularity. As Bill Maher recently said—and he’s a supporter—the number of delegates she won can be counted on one hand—if that hand has no fingers.

I hasten to assure you that my remarks are not partisan. I am an equal-opportunity hater. I have two middle fingers, one red and one blue. So think what you will of Reagan. Just bear in mind the dangers of dullness. Bear in mind if you must what John Lukacs said of him: the problem with Reagan isn’t that he was an actor; the problem is that he never stopped being one.

And compared to some of the greats Reagan hardly qualifies as witty.

Lincoln apparently said of Douglas, “His argument is as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had been starved to death.” Lincoln also said, “He can compress the most words into the smallest idea of any man I know” and “He’s got his headquarters where his hindquarters ought to be.” Ann Richards said of George H.W. Bush, “Poor George. He can’t help it — he was born with a silver foot in his mouth.” Lloyd George said, “When they circumcised Herbert Samuel they threw away the wrong bit.” When Calvin Coolidge died, Dorothy Parker asked, “How could they tell?” Sixty-one years ago Viscount Hailsham delivered a zinger that, strange to say, no one was clever enough to recycle with respect to the GOP: “A great party,” the viscount said, “is not to be brought down because of a squalid affair between a woman of easy virtue and a proven liar.” Christopher Hitchens said of Jerry Falwell, “If you gave … [him] an enema he could be buried in a matchbox.” Of whom would you use Disraeli’s mot juste? Mitch McConell? “If he fell into the Hudson, that would be a misfortune, and if anyone pulled him out, that would be a calamity.” Of Disraeli himself the great Quaker orator John Bright said, he is “a self-made man who worships his creator.” The Scottish-born journalist and Times editor James Reston said of Richard Nixon, “He inherited some good instincts from his Quaker forebears, but by diligent hard work, he overcame them.” The comedian and master of one-liners Jack E. Leonard said to Perry Como, “You have a very fine voice—too bad it’s in Bing Crosby’s throat.”

I admit that that isn’t even remotely relevant to the topic. But neither is H.L. Mencken’s definition of conscience: a mother-in-law whose visit never ends.

Surely Charles Maurice de Talleyrand’s famous line could be applied to any number of people, probably to Nancy Pelosi in her prime, assuming she had one, and, from what I hear, to Nancy Reagan in hers: “In order to avoid being called a flirt, she always yielded easily.” You may recall that Sir Clement Freud dubbed Margaret Thatcher “Atilla the hen.” Boris Johnson was a good dartboard for receiving the pointed vitriol of his enemies, but then sometimes he was not a bad thrower of splenetic darts himself. He said the Tory party had “become used to Papua New Guinea-style orgies of cannibalism and chief-killing.” He was persuaded that he should apologize for this remark, so he did. He said: “I mean no insult to the people of Papua New Guinea.” And why more people in public life don’t quote Shakespeare is a very great wonder. When Orlando meets Jacques in As You Like It he says, “I do desire we may be better strangers.”

A little wit and the revival of the well-made insult could do us a lot of good, for we live in a remarkably humorless moment, thanks in part, probably, to several academic isms that have all the jocularity of an Ingmar Bergman film and less appeal than a gas-station bathroom.

But a revival of wit—by which I mean intellectual ability and mental quickness, the ability to see likeness where everyone else sees only difference (in other words, “wit” in its obsolete definitions)—this revival will require that a few other conditions obtain: for starters, a witty insult must be artfully expressed. As the famous trial lawyer Louis Nizer almost said (Nizer is responsible for saving the movie Carnal Knowledge from oblivion—and also for giving Art Garfunkel a second chance at mediocrity)—as Nizer almost said, “A graceful [insult] is worth a thousand [taunts].” (He actually said, “A graceful taunt is worth a thousand insults.”)

Now the crass insult would merely be beyond comment were it not also beneath contempt; the artful insult, by contrast, tells us that the wit delivering it at least had the decency to think about and to craft the insult well. And that, I think, is a sign of both respect and civility. It is not merely wordplay to say that if a man is worthy of being on the receiving end of a good dig, then the dig bestows upon him a degree of dignity. And dignity requires of us the lost art of laughing at ourselves or the ability, as I will say later, to trifle with gracefulness—another condition that must obtain in this revival: To trifle with gracefulness.

And of course the revival will also require charity, but charity is the last thing I want to talk about. I mean that literally: it’s the last think I’m going to talk about. I’m going to say something about the pride and passion of man and how hopeless we are before pride and passion if we are incapable of charity. But for now I intend to go on being uncharitable.

Some of you live in a state whose governor is a sorority girl so far out of her depth that she might as well be taking a course for football players at Alabama titled “The Best Soliloquies from the Silent Film Era.” The evidence is everywhere that we are governed by badly educated plutocrats so verbally inelegant, so rhetorically unsophisticated, and so historically oblivious that they would surprise no one if they said a relative clause is a first cousin dressed as Santa.

But our media personalities, who were once called “journalists,” suffer from the same deficits. Suffer me to point out in passing that our erstwhile august but now clueless Paper of Record has endorsed presidential candidates from one and only one political party going all the way back to 1956, and yet there is no indication after the ideological flip-flop the two major parties have undergone, especially in the last four years, that the paper of record is going to break with nearly 70 years of mindless habit, switch over, and stick with its principles instead of with its party. For who now is anti-war, anti-FBI, and anti-CIA? Who is anti-ATF, anti-CDC, anti-censorship? Who distrusts power? Who follows the money? Who wears t-shirts that say “Question Authority”? All of this can be summed up in: WTF?

None of this matters to the current plutocrats. They don’t care that their party is now performing on the war machine, and on the agencies of the war-mongering party in power, extraordinary and heretofore undocumented acts of fellatio. And this moral abomination is enough to make a man reach once again for his Chesterton, who said, and I quote, “Men are ruled, at this minute by the clock, by liars who refuse them news, and by fools who cannot govern.”

Liars who refuse them news, and fools who cannot govern. We should all hope to write a sentence that will be more relevant in 115 years than it is right now.

But it’s not all bad. The liars and fools in league with each other almost have it right; they really do almost have it right: I myself do not admire Mr. Trump, but he is indeed a threat to their hypocrisy. An existential threat, I should say. Apparently they’re all reading Camus now, even Oprah.

If you can’t make the shills on the alphabet news channels or on Vixen News get this, at least say it with a wry smile. And say it in an interesting way.

Now I just learned this morning that we have a general election coming up, which is bad enough, and that the people duking it out for the privilege of sitting on the Oval Throne, the porcelain executive seat (and because we’re in west Michigan I must pause to remind everyone that it was a Dutchman who invented the toilet seat, though it took a German to cut a hole in it)—the people duking it out don’t know how to turn a phrase; they don’t know that a phrase can be turned. They don’t know that there are such things as phrases.

Mr. Trump, the great pumpkin in a comb-over, can occasionally be funny. Ms. Harris, the pantsuit in search of a concrete noun and a subject and predicate—and fondly hoping that all three, if they exist at all, will conveniently fall out of a coconut tree, so the tree can be unburdened by what has been … hanging from it—she has little to her rhetorical credit save actually dropping an F-bomb once in a public address. I don’t approve of this, at least not in public addresses, but I’ll warrant that it is a sign of life every bit as convincing as a giggle or an answer consisting mostly of rewarmed Hungarian goulash.

But somewhere along the line these two monstrously grotesque carnival sideshows, which all of us are supposed to take seriously, have seen too few balanced clauses and too many unbalanced budgets. What comes out of their mouths is little more than what any fool might write if only he would abandon his mind to it. Political ambition being the scourge that it is might nevertheless improve at least a little if those pole-vaulting on it would read some eighteenth-century prose. For it was then, after all, that Dr. Johnson said of a certain lawyer, “He is not only dull himself, but the cause of dullness in others.” But we are treated to the constant pitchforking of lies and malapropisms and Teufelsdrök —on the one hand claims that this policy or that will be bigger than anything that has ever been signed into legislation in the history of the world, bigger than anything on Andromeda—and, on the other hand, claims about the significance of the passage of time, which, when you think about it, there is great significance to the passage of time in terms of what we need to do—right?—in the context of all in which you live and what came before you.

The only reason it’s not really as bad as it looks is that it’s worse.

Now to defend the urbanely delivered insult I will compare it to something clearly less civil: Political yard signs during election seasons. These are unneighborly and uncivil. Along the road front of the scrabbliest most junk-bestrewn unkempt domicile on my country road there is a sign instructing me to stop pretending that my racism is patriotism. Now the beneficence of free tuition from a political philosopher living on the set of Sanford & Son is a great asset to our township—if you spell “asset” with two fewer letters than normal. And it won’t surprise you that there’s one of those multicolored “In This House We Believe” signs. As Emerson said, tell me your sect, and I’ll tell you what you think. It would be uncivil of me to paint over this sign so that it reads “In This House We Believe that tautologies are tautological,” but I confess I am tempted.

Another sign: “Silence is Violence.” But is it really? Does a man being beaten by another man with a baseball bat cry out to his assailant, “what have I done to you that you should be so silent with me?”

For a pretty good stretch of years we in the civilized world have maintained that having different words to represent differing realities allows for a certain precision of thought. But now it is permissible to say in public, without any pushback, that a chimpanzee is a pork chop, and woe betide him who dissents.

It isn’t civil to shout nonsense at your neighbors.

And now I’m going to spare you two very funny paragraphs on the incivility of cell phones and car horns.

And here’s where I skip the paragraph on the incivility of the academy, except to say that it should come as no surprise to anyone who has witnessed professors in their little pre-schools of tenure that their students show no signs of civility or virtue but do show all the signs of incivility and virtue-signaling. It is no wonder that they honk their horns, shout on their cell phones in the commons, and have signs in their yards telling other people what to think.

Don’t tell other people what to think. If you would be civil, remember one very simple rule: don’t be an asshole. Is it that difficult not to be a walking version of your lower drain valve?

(I’ve just given you only one of the reasons Calvin University has never named me alumnus of the year.)

And now, briefly, I want to stop being serious and tell a few jokes.

I have been suggesting in effect that wit is an intermediary between goodness on the one hand, which is in very short supply, and what for the sake of vividness I shall call assholery on the other, of which there is presently such a great surplus that it is available at a very low price—at or below cost, I should say. You can’t buy a Yugo this cheap. You can’t buy one of Bill Kauffman’s remaindered books for less. But wit is a limited good—limited but still necessary; it is not quite analogous to those techniques proffered to us by the mountebanks in the marketplace as solutions to problems not susceptible of technical remediation—and certainly not of legislation—but it is, I think, a sign of something good aborning.

I would therefore say, and say plainly, that although dullness must be defeated, and that although we must beat it back as if it is the wilderness and we the self-righteous Puritan settlers endowed with all the metaphysical sanctions we need to beat it back, we must also remember that we are clearing ground for a very particular kind of settlement. It is a settlement that a solid liberal education is or can be the carrier of.

But such an education, I hasten to add, is not the thing itself. And let’s be clear: liberal education, like silence, is not up for redefinition. Consciousness-raising such as you see on campuses today won’t cut it. What we need, among many other changes, is to give a real version of liberal education a chance. And we must scrap forthwith all the BS versions of it that thrive in the age of academic departments and pseudo-disciplines that end in the word “studies,” where protesting has replaced paper-writing and slogans have replaced sentences—the kinds of slogans that end up on yard signs. And we should include wit in this real version.

And believe it or not I have come round at last to charity. But again: I speak of liberal education as a vehicle of charity, not as charity itself, for, as Cardinal Newman once said, what a liberal education makes is not a Christian but a gentleman.

It is well to be a gentlemen, [he said], it is well to have a cultivated intellect, a delicate taste, a candid, equitable, dispassionate mind, a noble and courteous bearing in the conduct of life;—these are the connatural qualities of a large knowledge; they are the objects of a University…; but still, I repeat, they are no guarantee for sanctity or even for conscientiousness …

I interject to clarify: smarts don’t cut it. Newman goes on to say that when you can quarry granite rock with razors or tie a vessel to a dock with a thread of silk, then you may “hope with such keen and delicate instruments as human knowledge and human reason to contend against those giants, the passion and the pride of man.”

In other words, knowledge and reason are no match for our gargantuan vices. The giants passion and pride cannot be held at bay by the ignorance that prevails in public discourse and certainly not by the bluster it hides behind. Wit as I have used it is useful, but again only as handmaiden to the charity a genuine liberal arts education is not the source but the vehicle of.

[A real liberal arts education, Newman said] is the great ordinary means to a great but ordinary end; it aims at raising the intellectual tone of society, at cultivating the public mind, at purifying the national taste, at supplying true principles to popular enthusiasm and fixed aims to popular aspiration, at giving enlargement and sobriety to the ideas of the age, at facilitating the exercise of political power, and refining the intercourse of private life. It is the education which gives a man a clear conscious view of his own opinions and judgments, a truth in developing them, an eloquence in expressing them, and a force in urging them. It teaches him to see things as they are, to go right to the point, to disentangle a skein of thought, to detect what is sophistical, and to discard what is irrelevant. It prepares him to fill any post with credit, and to master any subject with facility. It shows him how to accommodate himself to others, how to throw himself into their state of mind, how to bring before them his own, how to influence them, how to come to an understanding with them, how to bear with them. He is at home in any society, he has common ground with every class…; he knows when to be serious and when to trifle, and he has a sure tact which enables him to trifle with gracefulness and to be serious with effect…. He has a gift which serves him in public, and supports him in retirement, without which good fortune is but vulgar, and with which failure and disappointment have a charm. The art which tends to make a man all this, is in the object which it pursues as useful as the art of wealth or the art of health …

I have just quoted at length from Newman’s fifth and seventh discourses in The Idea of a University. Find me one in a hundred university presidents or one in a hundred college deans who has read this book. Find me one in a thousand professors. Find me one in ten thousand politicians.

It is terrible to contemplate how few risks I have taken here. And I don’t even mean to raise the issue of jokes directed at Bill Kauffman, who is the very face of FPR—and also its forehead. Bill will get even with me, rest assured, and to get even with him I’ll have to wait for the cocktail hour that all of you will be praying for during his talk.

You have been very patient.

Image via Flickr