“Who against hope believed in hope...” —Romans 4:18 (KJV)

“With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” —Marin Luther King Jr., "I Have a Dream"

The end is nigh. If not the end, at least some catastrophic turn of events that will forever change our world for the worse: nuclear war; mass extinctions, rising water levels, and volatile weather; various AI-administered dystopias. You can provide other worst-case scenarios. They are manifold. Higher rates of mental illness and collapsing birth rates are complex phenomena, but surely this sense of impending doom seeps into both. Our time is one of anxious fear, resigned pessimism, or too-chipper (desperate?) optimism that technology or one’s preferred candidate will save the day. According to the contemporary philosopher Byung-Chul Han, what we really need is a hope free of optimism, one that fully acknowledges possible catastrophe. Han’s new book The Spirit of Hope meditates on the difficulty but also the necessity of such hope in our time.

Unlike optimism, Han argues, hope does not deny the problems we face or their scope. It often emerges out of or near to a despair in which our plans and certainties are rattled. Such hope knows what it does not know: the future. It sees in the uncertainty of the future, in its contingency, the possibility—however slim—of renewals, of paths around or beyond the doomsday scenarios. “Those who hope,” Han writes, “put their trust in possibilities that point beyond the ‘badly existing.’ Hope enables us to break out of closed time as a prison.” Hope challenges the sense that we are on an irreversible course toward a certain end. For hope, the future is not a runaway train on a fixed track. There might be a way that we’ll come out of this OK.

This kind of hope grants a certain patience about the future, but it also allows one to act, sustaining the day-to-day in a richer way, seeking and pursuing remedies for the problems plaguing us. Unlike frenetic busyness, unlike the compulsive achievement-seeking that Han has diagnosed so trenchantly in earlier books like The Burnout Society, hopeful actions are more deliberate and decisive, more attuned to the world beyond the ego. “Those who act with hope,” Han explains, “act audaciously and are not distracted by the rapidity and toughness of life. However, there is also something contemplative about hope. It leans forward and listens attentively. The receptivity of hope makes it tender, lends it beauty and grace.” Hope is future-oriented, but it is so in a way that illuminates, that gives us back, the present: “To the hopeful, the world appears in a different light. Hope gives the world a special radiance; it brightens the world.”

Han insists that hope ultimately gathers others into a community. Hope is a rallying cry. It can galvanize. Hope not only transcends what we know for certain, but it also transcends the limits of what I can control or accomplish on my own. One of the best chapters in The Spirit of Hope challenges the existentialism of Albert Camus, who expresses a common notion (at least from the twentieth century onward) that hope is weak, static, resigned. Han rejects this as a specious account. Camus’s charges might stick to an everything-will-turn-out-fine optimism, but hope “ensures that, despite all the ills of the world, we do not resign ourselves.” Han frequently draws on the very different existentialism of Camus’s older contemporary Gabriel Marcel, who during the dark days of World War II gave a profound talk on the need for a resilient, open sense of hope. (Han notes that Camus himself strikes more hopeful notes about hope in his Nobel acceptance speech.) For Han, as for Marcel before him, hope is the truly tough-minded and courageous disposition, yet it is also caring and graceful. It encourages “solicitude that lovingly and affectionately turns towards others, that takes care of them.” It is “friendly,” to use one of Han’s favorite words. It draws people together in solidarity. It draws them into a “we.”

Han is a trenchant critic of the way screens have reshaped our existence and the way “big data” has gained such authority. He hints that these, too, limit or even stifle hope. The algorithm seems to curate while laying a trap. It lures us with yet another post, another link that promises to either console or outrage. Han insists that despite the seeming open-endedness and variety of the Internet, our digital devices imprison us in the “hell of the same.” We become used to having the answers at our fingerprints. We think that the latest data set will give us the power to predict or control the future. All of this is antithetical to hope, which involves broad openness to others, the world, and an uncertain future. Hope involves an element of imagination, a “longing,” that can open “a field of possibilities.” Big data can only endlessly calculate within itself. We easily confuse its abstractions and quantitative reach for the whole. Hope, on the other hand, can envision breaks and possibilities beyond such soul-constricting calculation.

Han suggests that our crisis of hope also comes from a “crisis of narration.” (This is the title of another of his recent books, where he contrasts true narration with a widespread commodified “story selling”—“apocalypses sell,” he reiterates in The Spirit of Hope.) Han points to the loss in the West of shared Jewish and Christian narratives that cultivate a hopeful openness to the future despite the trials and tribulations, the inevitable falls and failings, of the present day. These narratives can be and have been distorted in all kinds of ways, of course, from the saccharine to the sensationalist. They probably have some genetic relation to the narrative of progress that displaced hope with optimism in modernity and, in their grimmer forms, to our penchant for apocalyptic thinking. But at their best, and far more often than their critics like to acknowledge, shared religious narratives give normal people the means to deal with difficult situations. (While nuclear weapons represent an unprecedented means of destruction, we are hardly the first generation to face daunting challenges.) Such narratives give people an important role to play in an unfolding drama that begins before them in the past and stretches beyond them in the future. In this way, hope is not just about the future and present but also the past. Shared religious narratives can grant a hopeful orientation to the whole of life.

Han studied theology alongside philosophy, and throughout this study he draws insights from Christian thinkers ranging from St. Paul to the recently deceased Jürgen Moltmann. Han considers hope’s close relationship to the other two theological virtues of faith and love, and he insists that while it can be cultivated, hope is fundamentally a gift—a grace, to use the theological language. In the harshest of situations, when hope seems hopeless and is thus all the more important for perseverance, hope reveals itself to be anchored not in this world but in the “transcendent.”

Those familiar with Han’s earlier work should find this to be a satisfying new study. While Han has at times seemed apolitical or quietest, even baffling some readers of his recent study Vita Contemplativa with his notion of a “politics of inactivity,” here he insists on the necessity of hope to any healthy politics. He offers extended reflections on Martin Luther King Jr. and Václav Havel. Han has long advocated a contemplative remedy to widespread hyperstimulation and burnout. Because of this, he has at times been accused of offering no real call to action. On a cursory reading, he instead seems to offer a merely therapeutic call to meditation. That was never really the case. He has always insisted that contemplation prepares for more deliberate and decisive action—for true action. But a change of emphasis in this study foregrounds such action in a more explicit way. In earlier studies, he focused on what he calls “profound tiredness” or “profound boredom” as a fundamental mood. In such a state, the ego relaxes and thereby re-opens to others and the world. In this state of maximal dilation, new beginnings are possible. But skeptical or uncharitable readers can easily roll their eyes at “profound tiredness” as a departure point for action. In this new study, Han instead focuses on hope as a “fundamental mood,” one that has a contemplative dimension but is also clearly oriented toward action.

Some still won’t be impressed. The book is repetitive in places and stays at the level of theory. If you are looking for practical steps to slow climate change or achieve world peace, The Spirit of Hope will disappoint. If you are looking for arguments that are thoroughly qualified and nuanced, you won’t like Han’s bracingly strong claims. But I suspect that this stirring book will strike a chord with many readers of Front Porch Republic. I am convinced with Han that we need to cultivate the spirit of hope in our fearful times.

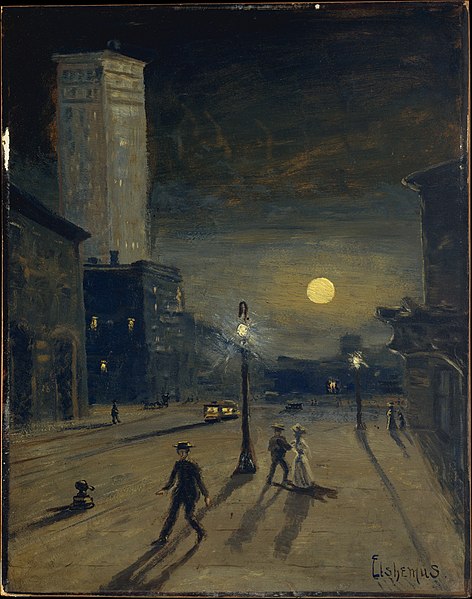

Image credit: Louis Eilshemius, “New York at Night” (c.1910) via Wikimedia Commons

1 comment

Rob G

I’ve just finished the book, which I enjoyed very much (although I could have done without the final chapter on Heidegger. Its key critique is helpful but it might have been shorter and turned into an appendix.)

Of the many striking passages that I noted one in particular stood out: the discussion on page 65 of the idea that hope draws on “traces” of the remembered past. I wonder if this is part of the explanation of Gen Z’s frequent invocation of “nostalgia.” It’s apparent that among that generation that a certain hopelessness prevails; it’s reflected in their music, their reading (or non-reading), even in their demeanor. Related to this is the appeal of a nostalgia which tends to look back at childhood wistfully, an odd thing for people so young.

Is it possible that this nostalgia is serving as the supplier of those “traces” of the past which are in turn granting them a semblance of hope, even though it’s not necessarily understood by them as such? This question stems from a conversation I had with my 22 y.o. nephew about why people his age like “sad” music so much. His explanation was that the music puts them in a “nostalgic” mood, and that that temporarily relieves their sadness/hopelessness. In so many words his point was that the sadness of reflecting on a lost childhood is a relief from thinking on the negativity of the present.

Comments are closed.