William and Alice James set out at 6am from their Massachusetts home. A small wicker basket sits on Alice’s lap, wrapped in a white flannel blanket. They stop to gather pine, oak, and birch leaves, along with wild flowers, ferns, and grasses. Soon they arrive at the James family plot. They set tree sprigs, flowers, and ferns in the basket—now revealed as a casket holding their baby boy, eighteen months old, known in the family as Humster. He died two days ago. They bury Humster under a young pine tree next to James’s father, Henry James Sr. “It was as lovely and touching a little sight as you ever looked on,” James says. It is July 11, 1885.

The next month, on an unusually hot August night, James returns to the Cambridge home on Appian Way where his young family had once lived. He stands in the street and “looks at our old empty house under a clouded moon,” staring up at one window on the second floor. Behind its shutters lies the room where Humster was born. “It must be now,” James writes his cousin the next day, “that he is reserved for some still better chance than that, and that we shall in some way come into his presence again.”

Interactions with the hereafter come to dominate James’s research. “Immortality is one of the great spiritual needs of man,” he says. “The surest warrant for immortality is the yearning of our bowels for our dear ones.” The heartbroken father seeks confirmation and assurance, leading him to declare in 1897, twelve years after Humster’s death: “Religion is the great interest of my life.”

But it was a long time coming.

“A new kind of sympathy”

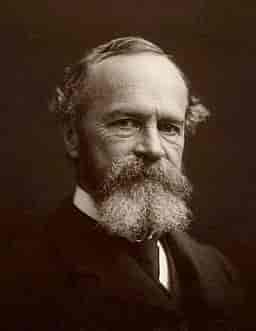

Thirteen years before his son’s passing, in 1872, James is recruited by Harvard president Charles Eliot to lecture on vertebrate physiology. By 1875 he is teaching one of the university’s first psychology courses, “The Relations between Physiology and Psychology,” strongly influenced by his trip to Germany in 1867-68. James’s trimmed beard, intelligent blue eyes, and incisive lectures are well known to his students, who include Theodore Roosevelt, W. E. B. Dubois, E. L. Thorndike, and Walter Lippmann. He also advises Gertrude Stein on her automatic writing project.

The popular instructor is not easily pigeon-holed. He is excited about the accuracy of Charles Darwin’s findings, for example, but agrees with the English biologist that it is naïve to dismiss God out of hand. Rather, James holds with Augustine’s assertion that if scriptural interpretations contradict facts, the interpretations must change, not the facts. Psychiatrist Howard Feinstein notices other paradoxes in James: he studies medicine but does not practice; speaks German and French fluently but is no linguist; appears calm and positive but has a hint of sadness in his demeanor; thinks deeply on religion but is no theologian; applies strict scientific method but is no materialist. “Yes, Dr. James was a brilliant, complex man,” concludes Feinstein, “but there were many things one wanted to know about him.”

James is a rising star in his profession and as the eldest son enjoys the approbation of his father, Henry James Sr, a philosopher, theologian, and deep believer in a utopian path to grace. Henry has impressed on his family a sense that the eternal is reality and religion is not folly. James is close to his father, but frequently distant from his mother, Mary.

Only in his adult years, at age thirty-eight in July 1880, did his “heart flow over with a new kind of sympathy” for all that his mother had endured in life. Fortunately, this realization did not come too late. Two years after James wrote those words, Mary dies of bronchitis on January 29, 1882. She was seventy-two. James feels her loss all the more keenly for what he sees as his lack of warmth toward her.

Henry Sr falls ill that autumn. His prognosis is poor. A year younger than his wife, Mary, Henry faces the idea of death “with contentment,” his doctor observes. On December 18, Henry proclaims, “I am going with great joy,” truly pleased that he has “such good boys,” meaning William, Henry Jr, Wilkie, and his youngest son, Bob. His last words are filled with quiet wonder: “There is my Mary!” He dies a few hours later.

James is surprised at the grief he feels for his father. He did not expect to be affected so deeply. The death leaves him dizzy with a new thought. “The tremendousness of the idea of immortality,” he tells his wife. “If only he could be joined to mother.”

Three days later, after the funeral, James stands over his parents’ graves. “Darling old Father,” he says, “on the other side, let us hope and pray, dear, dear old Mother is waiting for you to join her.” James is not certain if he will see them in the afterlife, but “more than ever at this moment do I feel that if that were true, all would be solved and justified.” He stays in the cemetery for hours, sensing that his father can hear him, his brother Henry Jr observes, “somewhere out of the depths of the still, bright winter air.”

The loss of his parents has a galvanizing effect on James’s writing. Mourners frequently find ways to express their grief through creativity, as a means of survival and an act of love to honor their dead. James later admits that he did more writing in the spring and summer of 1883 than at any time before. “The gap left by Father is even greater than I supposed it would be,” he says. “Life can never again seem solid to me as it did a year and a half ago.”

The resulting landmark work, “What is an Emotion?” was published in the April 1884 issue of Mind. Much of the essay is anecdotal. James observes a corollary between emotion and action: that is, if we feel a certain way, our bodies react accordingly; therefore, if we simulate that reaction, the original emotion will return. Mind and body seem inextricably linked. James does not suggest that merely acting the part will engender genuine feeling; rather, actions may cause us to revisit powerful emotions, such as hearing a beloved song or catching a fondly remembered scent.

In the same paper, James asks what grief would be “without its tears, its sobs, its suffocations of the heart, its pang of the breast-bone?” Waves of weeping only serve to make sorrow more acute, he posits, rather than providing relief. Tears make it worse. Modern research demonstrates that this view is untenable; many mourners (myself included) feel a small sense of relief after a good cry. It is also an interesting position to take after his dual losses, but not a surprising one for James, well known for a cool attitude toward deep passions. His early letters reveal greater concern for harmful mood disorders than healthy grief.

Once, years earlier at age twenty-four, James had berated a friend for giving himself over to melancholy. This is understandable. James too suffered from depression and lethargy, as he put it. Four years after writing that letter, in 1870, James had a nervous breakdown. He was twenty-eight. The ensuing emotional, intellectual, and spiritual crisis led to his conviction that faith is not the result of an imposition of divine will; rather, we choose our beliefs with the freedom God has granted us, what James would ultimately call “the will to believe.”

Much has been written to refute James’s early stance on emotions, but in fairness, it was strikingly original for its time. And his views were about to change. Within two years, his thoughts on grief, the afterlife, and his life’s work would take a dramatic turn.

“The flower of the flock”

On November 15, 1883, less than a year after their parents’ deaths, James’s younger brother Wilkie passes. Alternately known as Wilky, Wilk, and Wilkums, he is thirty-eight when his heart condition and a long struggle with Bright’s disease finally take him. Wilkie was a legitimate Civil War hero, commander of one of the first black regiments, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. His leg was wounded in combat and continued to trouble him to the point that he considered having it amputated. Two months earlier he had written to James, “It looks as if it would not be long before I shall peg out.”

The death of a younger sibling bears many similarities to the loss of a child. Meaning-making, as modern experts call it, often takes on new importance after the passing of a brother or sister. This search may have led James to redouble his efforts to complete a collection of his father’s writings, The Literary Remains of the Late Henry James. The act simultaneously honors father, mother, and brother: “not only a filial but a philosophic duty.”

James’s seemingly sideways approach is familiar to Christine Valentine, Centre for Death and Society, University of Bath. Grief causes us to see the mundane in different, even strange ways, she says, as we “gain an appreciation of how ‘common sense’ experiences are not as self-evident as they may seem.” Cultural meaning plays an important role in how we deal with loss, such as when James puts pen to paper. “I beseech the reader from now onwards,” he writes in an unusually plaintive and vulnerable introduction, “to listen to my stammering exposition in a very uncritical mood of mind.”

The same month his father’s anthology is published, James’s third son, Herman, is born on January 31, 1884. At the time, he and Alice have two children: Henry III, called Harry (age 6), and William, called Billy (age 3). Neither boy seems to mind that the baby is the apple of his father’s eye, “the flower of the flock.” James takes to calling the chubby and irresistibly jovial toddler Humster.

In June of 1885, Humster falls ill with whooping cough. Within a few weeks Alice also contracts it. With his son and wife suffering each day, James dreams “that poor little Humster had a hooked nose and was moribund!” Their condition is soon diagnosed as scarlet fever.

Doctors referred to the malady as “pestilential,” “insidious and deceptive.” At a time when about half of all deaths were children below the age of six, the pandemic made matters worse. Scarlet fever’s mortality rate ranged from 16.7 percent to 33.3 percent, with most deaths occurring among the very young. Treatments were often as horrifying as the disease.

Samuel Hahnemann, founder of homeopathy, introduced belladonna as a curative that was much in vogue. Other methods included leeches, bleeding, cold and hot effusions, and a host of drugs of an emetic, purgative, diaphoretic, tonic, or narcotic nature. Every three hours, parents were instructed to force medicine down a child’s throat with a mixture that likely included an infusion of roses, with an excess of acid, made palatable with an additional quantity of syrup, one of the customary prescriptions of the day.

Coughing was treated with mustard or pepper poultices applied to the chest and neck, causing terrible blistering. It was customary to subject a suffering child to mild purging with castor oil or citrate of magnesia—misguided attempts to rid the body of infection. These remedies were worse than useless; they were often cruel.

“It brings one closer to all mankind”

By June 28, Humster’s condition was “precarious,” James writes a friend, with “constant bronchitis which is apt to be fatal.” By the first week of July, “Our poor little baby is in very critical condition.”

On Thursday night, July 9, 1885, after battling convulsions, colic, and pneumonia, Humster dies at about nine o’clock. He is eighteen months old. Years later, the heartbroken father observes, “every individual existence goes out in a lonely spasm of helpless agony.”

Many parents blame themselves for causing their sick child needless suffering and failing to comfort them near the end. In the first year after a loss, the bereaved often obsessively reconstruct events and replay the death in their minds. This blend of regret, self-recrimination, and sorrow may be particularly acute for fathers like James, who frequently show the highest level of grief for men in every bereavement category except guilt.

Watching his wife during Humster’s illness, James says, “made me for the first time understand what the word ‘mother’ means.” Here he pauses and adds, “We get these retrospective illuminations pretty late.” His revelation calls to mind another aspect of grief that is frequently ignored out.

Many parents, seeing the daily suffering of their terminally ill child, secretly hope for some type of alleviation. This may take the form of prayers for healing or, unconsciously, ambivalent emotions and seldom acknowledged desires for the misery to end in any way possible. The child’s death may then be followed by a sense of relief. This grief-relief phenomenon, as it is known, is often accompanied by guilt for harboring such natural feelings. “Though relief appears soon,” Michael Bullock with the University of Southern California observes, “the period of bereavement may be long and painful.”

Two days after Humster’s death, on July 11, the grieving parents bury him in their family plot. Prior to losing his son, James had dismissed such rituals as sentimental. Later, he confesses to an aunt that the ceremony meant a great deal to them: “There is usefully a human need embodied in any old human custom and we both felt this.” Well over a century later, modern researchers have found that such funerary traditions facilitate adjustment in powerful and positive ways.

James does not write in detail about his grief, but his interest in the invisible world increases in the aftermath of Humster’s passing. “It brings one closer to all mankind, this world old experience,” he writes of death. “It makes the world seem smaller and deeper and more continuous with the next.”

Such belief is often essential to survival, suggests grief expert Ronald Knapp with Clemson University, who found that parents cannot sustain a belief that their child is not in heaven. Knapp interviewed over three hundred couples who survived their children. He observes that the pain is long-lasting, acute, and requires an act of courage to face each day, even years after the death. There is only one way to ease the suffering: “The loss of a child is such a monumental ordeal for most families to deal with that reaching beyond the scope of the rational world seems the only sensible way of coping.” James would have agreed.

“We and God have business with each other”

In 1890 James publishes what will become a standard work, his two-volume Principles of Psychology. The book is praised across America and Europe by such influential colleagues as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. When James becomes a professor of philosophy at Harvard in 1897, he grows fascinated with the diversity of religion and humanity’s deep-seated appetite for spiritual involvement. He is “in love with variety and experience as he finds it,” as historian Jacques Barzun observes.

By May-June of 1901, James is asked to deliver the University of Edinburgh’s Gifford Lectures, one of the highest honors in a philosopher’s career. The discussions are compiled in a book, The Varieties of Religious Experience, in which James coins such well-known phrases as tender-hearted, tough-minded, sick soul, and stream of consciousness.

Respected biographer Richard Anderson notes that the lectures demonstrate how institutions, books, bibles, or church leaders do not hold inherent authority, which instead resides “in the actual religious experiences of individuals.” These vary between cultures and persons, James observes, but a connecting thread is the reality of each person’s conversion. Surprisingly, this insight led to the establishment of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).

The co-founder of AA, William Griffith Wilson, known as Bill W., wrote to Jung on January 23, 1961 that Varieties “gave me the realization that most conversion experiences, whatever their variety, do have a common denominator of ego collapse at depth.” AA responds to such collapse on an almost wholesale basis, Bill W. says, adding that “James, though long in his grave, had been a founder of Alcoholics Anonymous.”

For his part, Jung, who met James in 1909, wrote four decades later that he “was tremendously impressed by the clearness of his [James’s] mind and the complete absence of intellectual prejudices.” Varieties remains one of the leading texts on religion from a viewpoint of philosophy and experimental psychology.

“We and God have business with each other; and in opening ourselves to his influence our deepest destiny is fulfilled,” James informs listeners in Edinburgh. “God is real since he produces real effects.” Religious faith may not be easily dismissed as glandular secretion, nervous disorder, or the result of mental imbalance. Such observations are more than exercises in reason, James says. They are also acts of solace. “To anyone who has ever looked on the face of a dead child or parent, the mere fact that matter could have taken for a time that precious form, ought to make matter sacred ever after.” His belief leads to hope—and a search that shocks his colleagues.

“There is something back there”

In 1884, after the deaths of his parents and his younger brother, James had become a member of the English Society of Psychical Research. With Humster’s death, James grows more interested in questions of eternity and immortality. He helps to found the society’s American branch in 1885 with Alexander Graham Bell and Edward Charles Pickering.

The American Society of Psychical Research (ASPR) has a modest goal: to study psychic phenomenon under strict scientific conditions. The work is nearly chimerical, and at times frustrating for the researchers, though they manage to expose a number of frauds, whom James typifies with disgust as degenerative congeners. “I disbelieve in the substitution of ‘audiences’ for investigators,” he writes, “‘popular interest’ for investigation and newspaper tattle for facts.” However, there are a few psychics whom the ASPR identifies as legitimate, possessing “supernormal knowledge.” This gives James hope that human consciousness may exist beyond biological life.

James continues his ASPR work for many years. “I believe in psychical research and its endowment,” he says. He remains unconvinced that empirical evidence will ever be forthcoming. James is struck, however, by one startling discovery. A vast majority of mourners, perfectly sane and reasonable people, speak of spiritual experiences with their dead. Modern experts have confirmed his findings.

Medical clinicians Nadine Nowatzki, University of Manitoba, and Ruth Grant Kalischuk, University of Lethbridge, interviewed twenty-three bereaved persons who had reported seeing, hearing, or feeling their deceased loved ones. They then compared these findings with previous research and numerous historical accounts. Their results, published in 2009 with the professional journal, Omega, found that “the encounters profoundly affected the participants’ beliefs in an afterlife and attitudes toward life and death, and had a significant impact on their grief.” Such experiences provide a healthy sense of connection with the dead. This would not have surprised James, who views inquiries into immortality as essential to “fruitful relations with reality.”

By 1904, growing older and “just getting fit to live,” as he wryly puts it, James is even more convinced that personal immortality is not fantasy. “There is something back there that shows that minds communicate,” he concedes. “The world that our ‘normal’ consciousness makes use of is only a fraction of the whole world in which we have our being.”

James admits that demonstrative proof is fleeting but remains as committed to the work as his wife and his brother, Henry Jr, now a famed novelist. James asserts that orthodox science should not ignore clinical evidence. ASPR researchers have often recorded incidents, free of chicanery, when questions were answered, allusions understood, and thoughts met in ways that defied scientific explanation: “It is difficult not to take away an impression of having encountered something sincere in the way of social phenomenon.”

James retires from Harvard in 1907. His next two books, Pragmatism (1907) and A Pluralistic Universe (1909), suggest that philosophy transcends empirically based science in the exploration of truth, reality, and “free wild Nature.” His reference to natural scenery is not mere hyperbole: “I have often been surprised to find what a predominant part in my own spiritual experience it has played, and how it stands out as almost the only thing the memory of which I should like to carry over with me beyond the veil, unamended and unaltered.” James expands on this thought in The Meaning of Truth (1909), asking that if we feel something that lasts eternally, such as love, “what atom of logical or psychological argument is there to prove that it would not be felt as long as it lasted, and felt for just what it is, all that time?”

In the fall of 1909 American Magazine publishes, “The Confidences of a Psychical Researcher,” a summation of James’s hopeful, and often disappointing, work to methodically prove communication with the afterlife. After twenty-five years, he says, “I am theoretically no further than I was at the beginning.” Yet he also asserts that for there to be frauds, there must be something that they are replicating, borrowing in their deceit from legitimate experiences. Supernatural phenomenon and spiritual interaction are far more common than we suppose, he suggests. Coincidence fails to touch the root of the matter. This thought may resign him to posterity’s pit of judgment, he says in a verbal shrug, but he is writing the truth as he sees it:

I confess that at times I have been tempted to believe that the Creator has eternally intended this department of nature to remain baffling, to prompt our curiosities and hopes and suspicions, all in equal measure, so that, although ghosts and clairvoyances, and raps and messages from spirits, are always seeming to exist and can never be fully explained away, they also can never be susceptible to full collaboration.

Scoffers of James’s association with the ASPR seldom mention his lifetime commitment to rigorous scholarship and scientific skepticism. He is no fool, nor does he behave foolishly in grief or dotage, as some suggest. Rather, his paper displays the same keen reasoning that has been a hallmark of his career. Decades of sorrow and searching for clinical evidence have strengthened his resolve, tempered now by experiences that add up to more than disparate bits of empirical data. “There is a continuum of cosmic consciousness,” he concludes, “against which our individuality builds but accidental fences, and into which our several minds plunge as into a mother-sea or reservoir.”

A year later, in late August of 1910, he falls ill in England and returns with his wife to their home in Chocorua. He is immediately bedridden for what his doctor says is a failing heart. “Death has come to seem a very trifling incident,” he frequently tells his wife during his convalescence. Then, on the afternoon of August 26, Alice finds him unconscious in his sickroom. She climbs into bed with him and holds him in her arms until his breathing stops. William James is sixty-eight years old.

“I believe in immortality,” Alice writes. She admires her husband’s assurance that what he called the will to believe is by far the most vital part of living in a spiritual world. William’s body is dead, she tells a friend, but she knows he is “safe and living, loving and working, never to be wholly gone from us.”

Image Via: Store Norske Leksikon

2 comments

Art Kusserow

Mr. Bannon, I have appreciated all of your essays on FPR; likewise this one. I remember first encountering “Varieties” as a college student in the early ’70s and it is one of the classics I return to from time to time. Thank you for providing a different perspective on James’s life.

Mel Livatino

I needed to read this piece at this time in my life — very likely at ALL times in my life, but especially right now. I have written and published a good deal about grief in the nearly ten years since the loss of my wife, so the territory is very familiar to me. David Bannon has given all his readers a wonderful window on these twin topics of grief and immortality. This is the best piece I have read in the pages of FPR in the last three years. Thank you to Mr. Bannon and thank you to Jeff Bilbro for running it. God bless you gentlemen on this Christmas evening. Mel Livatino

Comments are closed.