Spring, 1969. My father finished feeding the cattle and hogs as the sun dropped in the western skyline. In the house, my mother supervised us kids as we donned our Sunday-best clothes. We ate a light supper in silence as the crimson sunset saturated the horizon outside the kitchen windows, a curtain of red bathing us in its reflective light. Dad changed from overalls into his grey suit and tie, starched white shirt, and a felt Fedora hat. As we looked at the clock and each other, my grandfather arrived from his farm down the road. We loaded into the family station wagon. It felt like an auspicious occasion. The day was April 1, 1969. The Eisenhower funeral train, carrying President Eisenhower’s coffin from Washington D.C. to his final resting place in Abilene, was passing through Missouri, and we were going to pay our respects.

That evening, we rode in deepening dusk and then darkness about one hour north of our home as the waxing gibbous moon rose in the eastern sky. People had gathered by the railroad tracks and more arrived throughout the evening. The song of spring peepers serenaded us like a sacred introit. Blooms of autumn olive, once recommended for erosion control and now an invasive species, filled the night air with their heady scent. We waited in silence. I looked around curiously. This was the first time an event from the news had intruded into my sheltered life.

A two-car train passed by slowly on the tracks.

“Is that the train, Dad?” we whispered.

“No, it’s a scout.”

I did not know what a scout was but knew my father would not welcome further questions. Around me, I could sense palpable anticipation. Within a minute, a long train came into view. My father stood at full attention in a military salute, something I had never seen. Tears streamed down his face. I had not seen that before either. The train had two engines and some baggage cars, with several passenger carriages bringing up the rear. Inside the brightly lit final car we saw, or thought we saw, Mrs. Eisenhower dressed in black sitting at a table. The moment passed by as though in a blur and was over.

We waited in silence. I looked around curiously. This was the first time an event from the news had intruded into my sheltered life.

Dad was no longer saluting, but he was still crying.

A Korean War veteran and a farmer, my father was a well-read student of American history. The death of President Eisenhower was cause for sorrow. A man who had led the American troops to victory in Europe in World War II, a President from the Midwest with humble roots who gave us the interstate highway system. That his politics were not perfectly aligned to my father’s values was of little consequence. After all, we lived in an agrarian neighborhood where Baptists, Catholics, and Methodists, as well as Democrats and Republicans, could all work together despite differences. Someone’s religious or political viewpoints could be overlooked in favor of neighborly relations when lives intertwined with cycles of planting and harvest, long-held grudges, and new gossip.

I knew that my father was a decent man, and that he respected President Eisenhower as a leader and as a man he believed to be decent. That evening, as we honored President Eisenhower’s life through the ritual of our presence, we became more decent people ourselves. Being decent is a mindset, but it also demands action. My parents were modeling what society does to honor decency, and to cultivate decency ourselves.

My young life to that time had followed a series of prescribed routines and rituals. We ate meals together as a family, nine of us seated around the kitchen table eating the food we had grown ourselves. We helped our parents in the barn and fields and in the house, rode the bus to school, and went to church. Within each of these broad categories of how our time was spent, there were embedded rituals, based on a growing understanding of how to treat people with decency. At meals we waited until everyone was served food before we began eating. No one grabbed the last piece of roast beef. In the barn and home, we did our assigned chores and then pitched in so all of us could be done. If a neighbor needed help, we quit what we were doing to offer our assistance. When a church member or relative died, we took food and sat with the bereaved. We grew in awareness of the broader narrative of humanity and community. Mistakes could be redeemed. People deserved second and third and fourth chances.

I did not know, yet, that this was part of a bigger pattern my parents were imprinting on us. We were learning the habit of decency in the home, in the community and in response to the wider world.

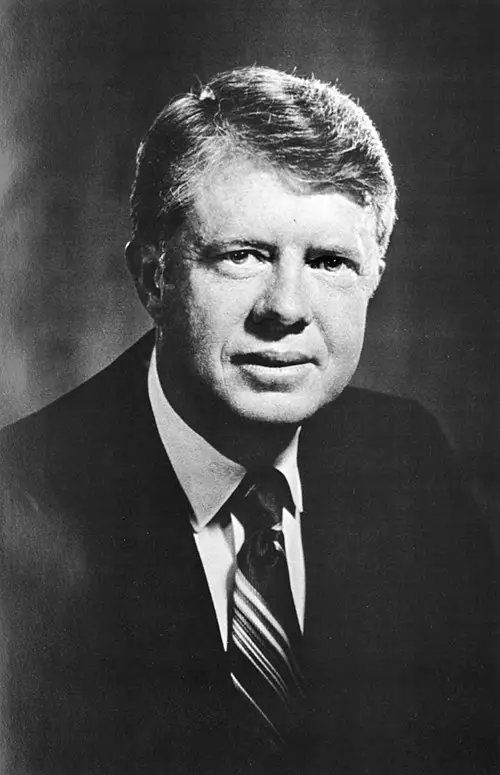

I have seen one living U.S. President in person. Today I’m mourning him.

There is a global outpouring of grief and respect for this ordinary Georgia farmer and Sunday School teacher who demonstrated extraordinary decency. Starting today, he will lie in state in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. President Carter was the only U.S. President who was a member of the Future Farmers of America (FFA), and it was my privilege to hear him address the FFA National Convention in 1978. As a teenager, I knew little of politics. To see any President would have been exciting, but this President was special to me. I felt connected to him because we shared our Christian faith and our calling to love and steward the land. He was an extraordinary man, who also happened to be the President.

While the world’s elite and powerful will pay tribute to him, perhaps it is the ordinary citizens who can show the greatest respect. People like my family—farmers, truck drivers, pharmacists, accountants, and school bus attendants.

What is a fitting ritual to honor his decency? Our rituals have changed since 1969, but the actions required by decency remain the same.

To honor decent people, we must show decency. I can visit a neighbor or an elderly resident at the nursing home. I can research the causes that President Carter cared about and see how I can become involved. Best of all, I can look around my own neighborhood and identify a need that deserves my energy and attention.

We are weary of a culture saturated with negativity and division. Decency is not the answer to all our problems. But when we demonstrate decency toward each person or group, we open the door for understanding and compassion. People all over the world, from every political spectrum, recognize President Carter’s decency. He’s a role model we all can emulate every day in our lives, homes, and communities.

In the past few years, I have mulled over his legacy in all its facets. What does his life mean to us as a nation? How can ordinary people act with decency in their homes and communities? Most importantly, what have we gained by having President Carter all these years as an example of how to be a decent member of the world community?

His long and productive life after the presidency distinguished him. He did not use his status to accrue wealth. His influence as a former president provided him an international platform to perform humanitarian work around the globe. He and Mrs. Carter drew attention to our responsibility to other human beings, whether it was voting rights, clean water, or mental health. He showed what was possible when people came together for a cause and acted out of decency. His loyalty to his family and his humility modeled the highest standards to a world where decency is in short supply. President Carter has remained in my conscience and heart, with great respect and affection, since I saw him speak in 1978 in Kansas City, as a naïve teenager.

Thank you, President Carter, from an ordinary citizen, for your life of decency and service.

Image via: PICRYL

2 comments

Ed Lindgren

A superb commentary. Thanks for sharing this, Alice.

David Naas

Amen and thank you.

I was born the year Truman was elected, but I do not recall him being President. I DO recall Dwight Eisenhower’s Presidency. It was a time of peace and security and decency in the face of provocation which ended when I was 12.

Here, well into the Twenty-first Century, it is reality that decency, courtesy, concern for others is mocked as being for “suckers”, by national “leaders”. Simple morality is dismissed as irrelevant, and honorable public behavior is quite unknown. (It isn’t merely the ignorant young punks who loudly employ foul language in Malls. Alleged adults do also, especially when they espy someone they think will disagree with them. Or even dare to “judge” them.)

The glue which holds society together has dried up and instead of local communities and National Community, we have a nasty anarchism which the self-centered of all stripes think is “Freedom”.

And across the board, from every niche and all “sides”, the only Unity people have is that they are one in claiming victimhood and declaring their grievances against a world which cannot make them happy, but is somehow supposed to.

Comments are closed.