Months ago, I embarked on a lengthy essay intended to convince people who are indifferent, or even hostile, that philosophy is a necessary human activity. Only upon further reflection have I determined this was futile.

For one, those much older and wiser than myself have presented the case for philosophy many times already before, and their arguments have been sound. St. John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical Fides et Ratio, reiterated the assertion of Aristotle that human beings naturally long for answers to philosophical questions. “It is the nature of the human being to seek the truth,” he wrote. “This search looks not only to the attainment of truths which are partial, empirical, or scientific; nor is it only in individual acts of decision-making that people seek the true good. Their search looks toward an ulterior truth which would explain the meaning of life.”

And, as he spoke to the innate longing for philosophy in the human heart, G.K. Chesterton reminded us that we all live downstream of philosophizing, whether done well or poorly: “Philosophy is merely thought that has been thought out. It is often a great bore. But man has no alternative, except between being influenced by thought that has been thought out and being influenced by thought that has not been thought out.” If man has no philosophy, Chesterton argued, he is left only to react to sensation and meaningless words and, therefore, is totally unequipped to deal with the complexity of the world in which he lives.

Yet, despite these perfectly reasonable defenses of philosophy (and many more), masses of people today seem not to care. In America (and I only assume it is the same in other English-speaking countries), there seems to be not only a widespread distrust of philosophy but an annoyance with it. On the surface, there exists a general hodge-podge of pragmatism, relativism, and skepticism that deems philosophy unnecessary, but below there is an undercurrent of frustration, sometimes even hostility, toward any careful and coherent philosophy.

Unfortunately, though deep down we all might want to know and live by the truth, sometimes we want other things more. We pursue those things even if that comes at truth’s expense. Only he who is already a philosopher (a “lover of wisdom,” etymologically speaking) makes the truth sovereign over all his other desires, as Plato taught in his Republic. This is what distinguishes the philosopher from other kinds of men. The philosopher loves the truth more than anything else, whereas other men love praise, money, pleasure, or power. They are not unphilosophical because they have alternative philosophies. They are unphilosophical because they have alternative objectives.

In Plato’s great allegory for the philosophical life, it is the philosopher who stumbles out of the cave by will or by fate and sees things as they really are. But when he returns to tell everyone else about his wonderful discovery, they ridicule him. They are content with the shadows on the wall. At least they think they are.

This is why philosophical arguments fail to gain a wide hearing: the very people who need to be convinced by them aren’t going to listen. Sufficient arguments are, after all, themselves philosophical. And this unphilosophical sentiment—call it philistinism—is nothing new. Socrates himself, Plato’s beloved teacher and main character in most of his dialogues, was forced to take hemlock by Athenians who disapproved of his method of philosophical questioning. Nor is it a rarity. All civilizations in human history have had their fair share of philistines. In numbers, they have likely far surpassed philosophers.

But common though they may be, they have not always been in control of society’s institutions. We know this because, in the past, there have been education systems (including universities) primarily dedicated to teaching the liberal arts. There have been serious artistic productions—poetry, theater, novels, and even films—and gatekeepers capable of distributing the best literature to a large audience who enjoyed it. There was at one time an aspiration for transcendent beauty that pervaded art, music, and architecture. There were generational myths and folktales, sacred rituals, standards of morality and excellence, and, in politics, an expectation of civility and statesmanship.

Today, however, things are quite different. The primary objective of education is to manufacture employees. Popular literature aims at sensation or propaganda or often both. People spend more time on Instagram, TikTok, or watching YouTube than they do reading books. Contemporary art feels nihilistic or utilitarian. Younger generations care very little about preserving the stories and traditions of the generations that came before them, relativism hinders moral and aesthetic discourse, and politics has become nearly synonymous with demagoguery and scandal.

But why is this the case? What gave our institutions over to the philistines and rendered our culture so particularly noxious to the philosophical way of life? I’m sure there are many reasons—technological, economic, and ideological—but perhaps uniting all these is a more general spirit that now prevails. Shortly before he died of prostate cancer in his home in Covington, Louisiana, in 1990, the Catholic novelist (and dare I say philosopher) Walker Percy boldly declared that “The old modern age has ended. We live in a post-modern as well as a post-Christian age which as yet has no name.” So, he gave it a name. He called it “the age of the theorist-consumer.”

Percy described an age where individuals constantly go back and forth between attempting to redefine the whole truth by a single facet of the truth (theorizing) and gratifying their appetites in a sorry attempt to distract themselves when their theories fail to make them happy (consuming). Their theories always fail to make them happy “because the theorist is not encompassed by his theory.” “One’s self is always a leftover from one’s theory,” he wrote. “For even if one becomes passionately convinced of Freudian theory or Marxist theory at three o’clock of a Wednesday afternoon, what does one do with oneself at four o’clock?” And, when he is consuming, he isn’t any more satisfied because he doesn’t really know what he wants. Percy warned: “The face of the denizen of the present age who has come to the end of theory and consumption is the face of sadness and anxiety.”

It’s clear why the theorist-consumer is so bothered by philosophy: his primary concern is not discovering and living by the truth but evading it in order to avoid the demands it places on him. The philosopher, in his search for wisdom, threatens to remind the theorist-consumer of precisely what he is trying to ignore and avoid.

But if we don’t like this state of affairs, what can we do about it?

Here’s what we can’t do: we can’t convince the unconvincable. We also can’t (or, at least, shouldn’t) let our dissatisfaction with the way things are use up all of our mental and spiritual energies. As it is a way of life, philosophy demands we spend at least some of our time and energy doing philosophical things: deep thinking, reading, memorizing, studying, discussing. We can disdain the shallowness, mediocrity, and mundanity of the contemporary culture all we want, but if we do not do these philosophical things, we not only will be unequipped to deal with the problems in our culture, but we will be part of the problem itself.

Recently, I stumbled upon an extremely fascinating and well-written essay by a New York City playwright who was disgruntled about the poor state of art and culture in the United States, specifically as it relates to the way the internet and social media platforms reward unsubstantial “content” over genuine literature and art. The playwright, Matthew Gasda, points to the multitude of online personalities, especially on places like X, who express an extreme nostalgia for a classical past they deem to be culturally richer than the dull, egalitarian, and impious present. Yet, these so-called dissidents contribute nothing to the development of any sort of classical culture, or culture at all. Rather, they circulate more unsubstantial content, only with a different aesthetic to that of pop culture.

“A high-culture simulacrum isn’t a high culture,” Gasda wrote. “‘Trad’ aesthetics, therefore, won’t fix anything, won’t produce an American renaissance. Neoclassical buildings and bodybuilders—the fetishes of the reactionary X.com crowd—reflect a hollow, ahistorical vision of human excellence. The circulation of semiotic tokens of classicism doesn’t purchase a living culture and cannot, in turn, commission real geniuses to commence real artistic work.”

This reminds me of a novel not written by Percy, but published by him in 1980, over a decade after its author committed suicide in his car in Biloxi, Mississippi. The novel, John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, is an absurd tragicomedy about a lazy, selfish, self-styled medievalist, Ignatius J. Reilly, who lives with his mother in New Orleans and has to find a job after she drunkenly crashes her car and damages a downtown building. In his forward to the novel, Percy describes Ignatius as a “slob extraordinary, a mad Oliver Hardy, a fat Don Quixote, a perverse Thomas Aquinas rolled into one.” I picture him as Chesterton’s evil twin (mustache and all), plagued with gastrointestinal issues, clothed in a flannel jacket and a green hunting cap with floppy ears, and, of course, missing the civility, cleverness, and mirth characteristic of the real prince of paradox. We laugh with Chesterton because of his wit (and because he can laugh at himself). We laugh at Ignatius precisely because of his folly. Everything is serious to him. He doesn’t get the joke, perhaps because he is the joke and is oblivious to himself.

Ignatius has a high opinion of the Middle Ages and thinkers like Boethius. He is critical of the contemporary world for its promiscuity and materialism. However, he makes this criticism the sole purpose of his life. For instance, he is so obsessed with bemoaning the poor taste of television and film that he spends a large portion of his time in the movie theater. He hates radical politics but finds himself engaging in revolutionary tactics—sabotage and eventually an attempt at an outright coup—when he finally gets a job in the corporate office of a textile manufacturer. He gripes against modern consumerism yet gorges himself full of hotdogs when he is fired from that job and gets another one as a street vendor.

As ridiculous and satirical a character as Ignatius is, he can be taken as a warning to those of us who find ourselves dissatisfied with a theorist-consumer world. Ignatius, at times, even grumbles about the necessity of an “inner life,” but it is quite evident to any reader that he doesn’t really have one. Rather, he stumbles through life as a buffoon who is completely unaware of his own absurdity, speaking words that seem to have lost their meaning. In the end, despite having defined himself by opposition to her, Ignatius rides off with Myrna Minkoff, his radical “sexually liberated” nemesis and ex-girlfriend whom he loves to hate. The two escape New Orleans together, and Ignatius avoids a trip to the mental hospital. They ride past an ambulance, sirens blaring and speeding towards Ignatius’s home, and make it to the marshes of Southern Louisiana.

The novels Percy wrote himself often also involve main characters who find themselves in opposition to the dehumanizing and mindless features of the world in which they live. However, unlike Ignatius, Percy’s characters sometimes manage to find meaning in their lives regardless. They do this not by a radical retreat from society or an outright war against it, but by returning to the ordinary things of everyday life and, as he describes it, searching for signs that point toward genuine transcendence.

Take, for instance, Love in the Ruins. Here, Dr. Tom More—a self-described “Bad Catholic,” namesake of the English martyr, and an ex-suicide—invents a device he believes will cure society from a disease he calls “angelism-beastialism” (which is really quite similar to the spirit of the theory-consumer). Dr. More’s world, set in the near future, is not unlike our own in that its inhabitants simultaneously obsess over abstractions and cheap pleasure. The U.S. has been torn asunder by political, racial, and religious fragmentation and is plagued by a cultish scientific materialism and a fervid movement to expand and protect euthanasia.

Ironically, as Dr. More tries to cure the spiritual qualms of his time (and subsequently win a Nobel Prize), it’s evident he suffers from the same ailment. In More’s own words: “I believe in God and the whole business but I love women best, music and science next, whiskey next, God fourth, and my fellow man hardly at all.” When Dr. More’s device gets into the hands of the wrong people, it actually exacerbates the problem, releasing a substance into the air that drives everyone into a frenzy of sexual impulse and violent rage.

While it rivals Toole’s Confederacy in its absurdity, Love in the Ruins concludes with sanity: Dr. More settles down, gets married, and, ultimately, lives an ordinary life. Most importantly, he returns to the sacraments. In the book’s epilogue, he finally makes a good confession after 11 years and receives the Eucharist.

Both novels can teach us something about how to respond (and how not to respond) sanely to an insane world. They can teach us something about how to be philosophers in a society whose institutions are dominated largely by philistines. They call not for an obsessive crusade or “the big search for the big happiness,” but the “Little Way” (to quote Binx Bolling, another one of Percy’s characters): simply living philosophical lives each and every day and not allowing ourselves to become detached from the things that matter most: our families, our friends, prayer, works of mercy, and the sacraments. Without these activities, any attempt to alter the culture will inevitably participate in its superficiality.

I do not deny the possibility that there are actionable steps, private and public, we could take to advance a philosophical culture: We could spend less time on our phones and more time in nature, in silence, in reading Great Books, or around the dinner table with our families. We could start a journal. We could read to our children. We could surround ourselves with friends who share our yearning for the truth.

On a grander scale, we could also support more traditional models of education. Already, new schools, both K-12 and four-year colleges, are sprouting up across the country dedicated to the liberal arts. We could also support genuine artists, poets, writers, architects, and musicians. Gasda suggests establishing “secular monasteries” at the public expense for artists to be free from “advertising and the algorithm,” the distractions of contemporary life. About that, I am undecided.

As long as we do live philosophical lives and share in that life with others, we can sprout a philosophical culture from the ruins of the one dominated by the philistines. After all, what is a culture but shared inner lives? What we call a culture now is but an anti-culture, the hollow shell of the institutions that were once built around the transcendent vision of an individual or group, as Gasda eloquently explains in his essay.

At the end of the day, while we are in this “desert of theory and consumption,” we have nothing else really to do but look for signs. And, as Percy explained: “There remains only one sign, the Jews,” i.e., “not only the exclusive people of God but the worldwide ecclesia instituted by one of them, God-become-man, a Jew.”

In other words, lost here in this desert, the philosophical pilgrim, the wayfarer in search of the truth, must, at one point or another, wonder back to Christ and His Church, the very institution instituted by God to carry us through the flood of this fallen world to its resurrection in the New Creation. And he must remain there to receive the signs of God’s grace, which no philistine can ever take away from us. “It is for this reason that the present age is better than Christendom,” Percy wrote. “In the Old Christendom, everyone was a Christian and hardly anyone thought twice about it. But in the present age, the survivor of theory and consumption becomes a wayfarer in the desert, like St. Anthony, which is to say, open to signs.”

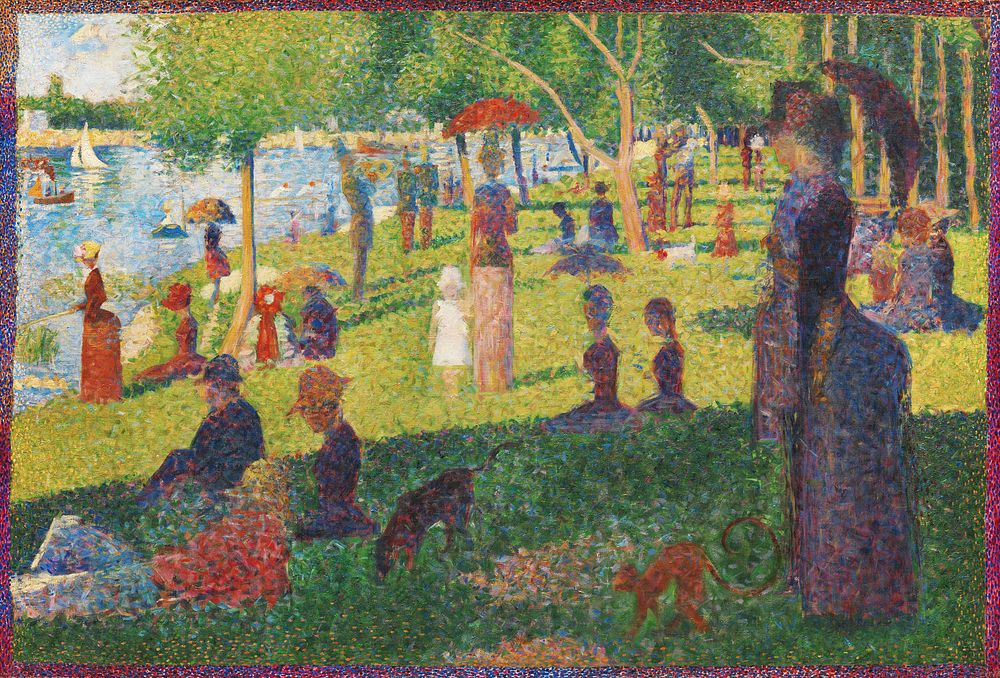

Image Via: Rawpixel

12 comments

Thomas

Pointed, if reiterative, essay. Modernity is beset by an overhumanized conception of reason. From Descartes to A.I. the humancentric functionalism of human consciousness has clearly developed into a philosophical impasse. If human happiness is a goal a less human way of thinking and living must be developed and believed in. This of course will be resisted by most. We have the death of Socrates and the crucifixion of Christ to remind and inspire us of this.

Franklin

I’ve never found people to be overtly hostile to philosophy but they don’t talk about it enough because of an overemphasis on a handful of hot button issues like race, class, and gender, which are important, but need to be integrated into a broader philosophical framework.

https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/research-studies-publications/public-opinion-poll/2015-public-opinion-poll/public-opinion-poll-arts-education-government-arts-funding

https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators

https://we1s.ucsb.edu/

Chuck Taylor

I love philosophy. It’s situation today is shared by quality literature and, to a lesser extent, history. I love philosophy but remain sceptical of it.

AP

I actually found this one very insightful… corresponds to my own experiences and articulates the solution better than I have been able to put into words myself… well done.

Jim Padilla

Accurate assessment of current non-thinking prevalence- philosophizing is alien to reflexive provocative memes. Boethius be dawned! Or so his legacy if apprehended would be received. But thank goodness the current new trend in teaching a classical curriculum may still preserve his legacy.

Dave Ray

You trivialized the direction you had started on which was initially universal and clear but in the conclusion clouded in your very particular set of religious symbols, as though the Christian message is really that obscure, esoteric and not universally humanistic.

And the derogatory tone could also be removed; it is a mere detriment to you piece.

David McEwen

If philosophy is understood as the love of wisdom, there are very few who truly do so.

David B Resnik

I don’t think philosophy is dead. It is very much alive. I work with many people in science, medicine, and technology who are deeply concerned about abstract and theoretical issues in their disciplines with philosophical implications and underpinnings, such as how to promote public, trust in science, deal with conflicts of interest, involve experts and the public in decision-making, and even questions like how to interpret data and assign authorship. In discussing these sorts of issues we often about knowledge, truth, and moral responsibility. Granted, we don’t spend much time reading Plato’s Republic but we do discuss philosophical issues. Another question that has come up in my work is the ethics of AI. This involve philosophical questions about what it means to be conscious, to think, to make moral judgments, and to be morally responsible.

Brigitte

Yeah, and almost none of these types of people engage with actual academic philosophy or even philosophers. I have many of these people in my family and friend groups, and as intelligent and capable as they are, their thoughts would be much more developed, interesting, and frankly true if they weren’t operating with the mindset that only STEM subjects are valuable and that they have nothing to learn from traditional or academic philosophy (or the humanities more broadly).

Chris Ramsey

I think you meant to write that “…the wayfarer in search of the truth, must, at one point or another, WANDER back to Christ and His Church…”?

Thank you for this essay!

Jon Schaff

Nope. It’s wonder, I suspect. As one of Percy’s most incisive interpreters, Peter Lawler, used to note, the key Christian hymn is the carol “I Wonder as I Wander.”

David Naas

Possibly, our author has begun with too narrow a definition of “philosophy”. Moderns have a philosophy, firmly imbedded in their collective psyche, reinforced at every moment by social and other media, and refuse to consider any other way.

It is called “Nihilism”. It is a very powerful philosophy. (I shall refrain from quoting Walter Sobchak’s line in “The Big Lebowski”.)

But, yeah, well, you know, that’s just, like, his opinion, man.

Comments are closed.