Is a Christian politics of love possible? Or does Christianity only work politically as a way to define who we should support and who we should oppose? To put it in Carl Schmitt’s terminology, is Christianity only politically efficacious in helping us determine who are our friends and who are our enemies?

These are questions that arise toward the end of Andrew Willard Jones’s new book The Church Against the State: On Subsidiarity and Solidarity. Jones, a historian who teaches in the theology program at Franciscan University in Steubenville, Ohio, brings a dizzying amount of knowledge to the subject of Christian politics. The Church Against the State attempts to lay out a comprehensive Christian political theory that stands in stark contrast to the liberalism that has dominated the Western world for nearly four centuries. In doing so, Jones juxtaposes the commitment to subsidiarity, most thoroughly fleshed out in the Catholic social thought of Pope Pius XI, with the notion of sovereignty, undergirded by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. What emerges is a stunningly broad and detailed analysis of both liberal and Christian politics. Jones’s yeoman effort mostly succeeds.

Jones’s Christian politics draws heavily on the thought of Thomas Aquinas, therefore derivatively on Aristotle. At the heart of healthy politics is friendship. Friendship, Jones consistently argues, is the enemy of tyranny. When we think of actual totalitarian regimes such as the Soviet Union or fictional regimes such as in Orwell’s 1984, friendship is difficult because there is a latent distrust in all relationships, even intimate relations of family. After all, Big Brother (or Comrade Stalin) is always watching.

If I am to know my duties to my neighbors, posits Jones, I need to know my neighbors. Even Thomas Hobbes and Carl Schmitt, thinkers illustrative of what Jones not-so-subtly calls the Kingdom of Darkness, must admit that politics operates by certain rules and conventions. In war, soldiers seldom indiscriminately slaughter the enemy. That is an indication that at least a little friendship remains even in the worst of conditions where politics has failed.

Emblematic of Christian political relationship is that of father and son. Implicit in this choice of model is an argument that authority figures should use properly lived fatherhood as a guide to political governance. In addition, citizens should in some sense see themselves as part of a family. The family metaphor puts even greater emphasis on the notion of the political community as being one of friendship. Christian politics is communal rather than individualist.

A father and son exist in a relationship defined by love. This relationship, Jones notes, is hierarchical without being exploitive. A Christian hierarchy, such as in the Christian family, does not necessitate that the “higher” possess greater virtue than the “lower.” Each plays the part appropriate to himself or herself. The intimacy of father and son allows the father to rule over the son, for the son’s own good, without domination. The father doesn’t rule based on abstract theories but based in prudence grounded in intimate knowledge of his son’s strengths and weaknesses. Further, age and experience enhance the father’s claim to rule. While a father has necessarily been a son, at least in the formative years the son has not been a father. In short, the father knows better what the son needs than the son does.

Jones expands on the notions of love and friendship via a non-familial example, that of a bricklayer. To become a bricklayer requires acquisition of certain virtues. First, acquisition of such virtues is made in community, not isolation. The bricklayer typically apprentices with a master bricklayer. The laborer learns about stone, technique, the varieties of bricks and which type is appropriate for which job. He lives virtues of hard work, fortitude, discipline, stewardship of resources, etc.

All of this is done in friendship. As noted, the bricklayer does not learn his art ex nihilo; he must learn from another and submit to a tradition. Further, he doesn’t lay bricks for himself. He must consider what his client wants. His goal is to do well by that client. Often his art will be done in conjunction with other artisans, such as carpenters and architects. All of this requires a high level of camaraderie. When disputes arise, they are settled based on previous experience set in custom.

The habits and virtues the bricklayer develops over time make him a better citizen. As Jones observes, the bricklayer’s virtues do not disappear when he comes home from the job site. His diligence, perseverance, forbearance toward co-workers, imbue his whole life. That we all know of bad fathers or skilled but vicious bricklayers only serves to show how the ideal of these two roles can serve as a guide. We only know what a bad father or bricklayer is because we know what the good version looks like.

The parental and vocational examples above are illustrative of a politics of charity, of mutual giving and receiving for the common good. If rightly practiced, little of what we normally call politics—that of coercion by law—is necessary. Jones concludes, “Law is fulfilled in grace, so the regime of coercive law necessarily recedes as the law of charity advances, as virtue is achieved and friendship deepens.” Essentially, this is what Jones means by subsidiarity: various spheres and hierarchies of power working in harmony toward a common good.

Contrast this with the reign of the liberal sovereign state. Jones’s critique of sovereignty is complex, expansive, and incisive. Jones argues that in the liberal sovereign state, contract is the only recognized form of social relation. Starting with a strong philosophical individualism, liberals reject the natural communalism of the politics of charity. For liberals, power is always exploitive. In effect, there are no real neighbors.

Jones makes surprisingly deft use of the thought of Michel Foucault. Jones commends Foucault’s analysis of power. Liberals, adopting the public/private distinction, falsely believe that there is some private sphere over which power has no hold. Using Foucault to deconstruct the liberal narrative, Jones shows the way in which liberalism reworks all institutions—not only the officially public institutions—in the image of liberal individualism. “Power is sneaky” is a fair one sentence summary of Foucault’s thought. Nowhere is that truer than in liberal politics.

For the liberal, conflict is the fundamental relationship between people. We only associate when there is force. Even when the association is contractual, thus nominally consensual, it is backed by the power of the state. This, ultimately, is Jones’s critique of sovereignty. In the era of the sovereign state, there is only the individual and the state. All people become, in effect, a creation, a persona in Jones’s terminology, of state power. My neighbor is not my friend but simply another persona who happens to live next to me. In effect, the sovereign is the source of all law.

The freedom of the modern state is illusory. If it is true, as thinkers such as Hobbes claim, that human relations are essentially competitive, then, as per Hobbes, we are naturally at war with each other. The sovereign’s job, then, is to monitor and adjudicate this competition that necessarily leads to conflict. Therefore, the power of the state must be all-encompassing. As Jones notes, the modern sovereign must be skeptical of institutions such as the family, the church, and friendship as these are rivals to the sovereign’s claim to adjudicate all relationships. C.S. Lewis, therefore, is correct in The Four Loves where he opines that friendship is politically dangerous as it sets an “us” apart from the whole.

Liberal economics, i.e., capitalism, Jones suggests, inexorably leads to calls for socialism. Liberal capitalism posits humans as merely self-interested. The liberal state has ruled any mode of communal activity outside the state as a threat to the sovereign. We are all in competition with each other. In fully bloomed liberalism, real friendship is difficult, as the current “friendship recession” suggests. To the extent traditional communal activity persists, it is largely parasitic on a non-liberal past that liberalism itself undermines. The only mode left to effectuate our natural communal longings is the state. Thus, the perennial attractiveness of socialism within the capitalist regime.

In the modern state, especially as articulated by Carl Schmitt, a friend is merely someone who is not your enemy…yet. The positing of competition and self-interest as the essential human condition leaves us open to the Schmittian “friend-enemy” distinction. We can see this in our contemporary politics as coalitions seem to form mostly based on hating the same people.

Peter Lawler argued that post-modernism wrongly understood was not really post-modern—literally “after modern”—at all. What we normally think of as “post-modern” is genuinely, Lawler argued, hyper-modernism, or modernism taken to its logical extreme. The individual is cut off from all authority or source of meaning outside the self, a plaything of power beyond his or her control. Foucault’s theory is akin to Plato’s cave in that the power that ultimately controls or defines us is unlikely to be the obvious sources of power such as the state or perhaps the educational establishment. Power is subtle, so subtle it will be difficult to perceive. Liberalism leaves the individual helpless to resist this power while telling the individual he’s freer than ever.

Jones’s politics differ from Foucault’s in that while Jones also sees power everywhere, power need not be exploitive. The question is not whether politics is ubiquitous. It is, Jones argues. The question is whether, per Foucault, politics is an arbitrary application of power or whether politics can include love and charity, as in the relationship between father and son.

As noted, Jones’s argument is capacious and complex. The capaciousness and complexity of the book undergirds a negative critique of the work. The book is highly didactic. The text would benefit mightily from more practical examples or narratives to illustrate its points. For example, one of the stronger elements of the book is its use of Orwell’s 1984 as a demonstration of the natural consequences of a politics of sovereignty. The book cries out for more examples like this.

Part and parcel of the book’s didactic tone, Jones often speaks in generalities that demand greater explanation. I’ll note only three.

Jones writes, “What has formed instead is a stifling regime of centralized power and conformity, a regime of mind-numbing homogeneity occupied by people who feel anything but free, but don’t understand why.” This claim is likely counterintuitive to many Americans, although I think it is true. Some examples of centralization and homogeneity are in order.

A few pages later, Jones notes, “In the liberal march to freedom, [Christians] are the ever-retreating but completely necessary tyrants, the enemies of human rights against whom the freedom fighters heroically contend, the defenders of dogma against whom the courageous scientists struggle, the stuffy prudes against whom the free-spirited youth must battle. We have all seen multiple versions of this movie—in fact, this is the plot of nearly all of our cultural productions.” I think Jones is certainly right, but could he not discuss an example or two? Even if one of those examples is Footloose? In a review, I noted the anti-Church subplot of the otherwise enjoyable recent Wonka movie. A discussion of this sort seems in order.

Finally, late in the book Jones writes, “Schmitt’s definition of politics as being essentially about the friend-enemy distinction resonate with a Christian people who increasingly feel the weight of their enemies.” Does Jones have any particular Christians in mind?

In short, one wishes Jones would speak a little more explicitly of our political situation today. We are left with allusions and suppositions, but nothing concrete. Jones avoids siding with or against any particular camp. There is virtue in that rhetorical choice. Still, I think the work’s thesis would be better explicated if Jones put in more historical, literary, or contemporary examples to render the theoretical more concrete.

More substantively, Porchers may ask if there are limits to the friend/family description of politics. Aristotle certainly thought that the city had a natural limit as we can be friends with only so many people. How much solidarity can I feel with people who live half a world away? As a Christian, I certainly recognize the image of God in all people. But practically speaking, would not an intentionally localist politics further a politics of friendship?

That said, I certainly recommend The Church Against the State. Those concerned with the aggressive liberalism of our day while pondering what a Christian politics might look like will benefit from Jones’s expansive knowledge. This book serves as a warning to those Christians who wish to “heighten the contradictions,” to use the tactics of the hostile Left against the Left, who see politics as an “us against them” fight to the death. Jones’s work should caution us against the temptation to use the power of the state to further apparent Christian ends. The politics Jones advocates seems to be one of decentralization married to a hearty evangelization. As Augustine noted, the Christian citizen is actually the best citizen as he has virtue and the common good as his goals. A Christian politics is not one of state power and Thunderdome-like conflict wherein only one survivor can emerge. As Lincoln famously put it:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory will swell when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

My citation of Lincoln might seem ironic as it appears toward the end of a review highly critical of liberalism. In my book on Lincoln I approvingly describe him as a liberal statesman (a point I’ve made here at the Porch before while criticizing liberal thought).

But I have also argued that Lincoln was a prudent, moderate statesman. Jones himself, in the preface of his book, observes that America is a mixture of liberal and non-liberal influences. There is a tradition of non-liberal/conservative thought and practice that helps temper American liberalism. Leo Strauss once noted that it is precisely those who are friends to liberal democracy, in whose company he placed himself, who should not “flatter” liberal democracy. Statesmen such as Lincoln and thinkers such as Tocqueville and perhaps Andrew Willard Jones are in Strauss’s company here. As friends of American liberal democracy they must point out its shortcomings, including the manner is which undiluted liberalism is corrosive to a polity.

Jones preaches a politics of civility. Of friendship. Of charity. That is a Christian politics.

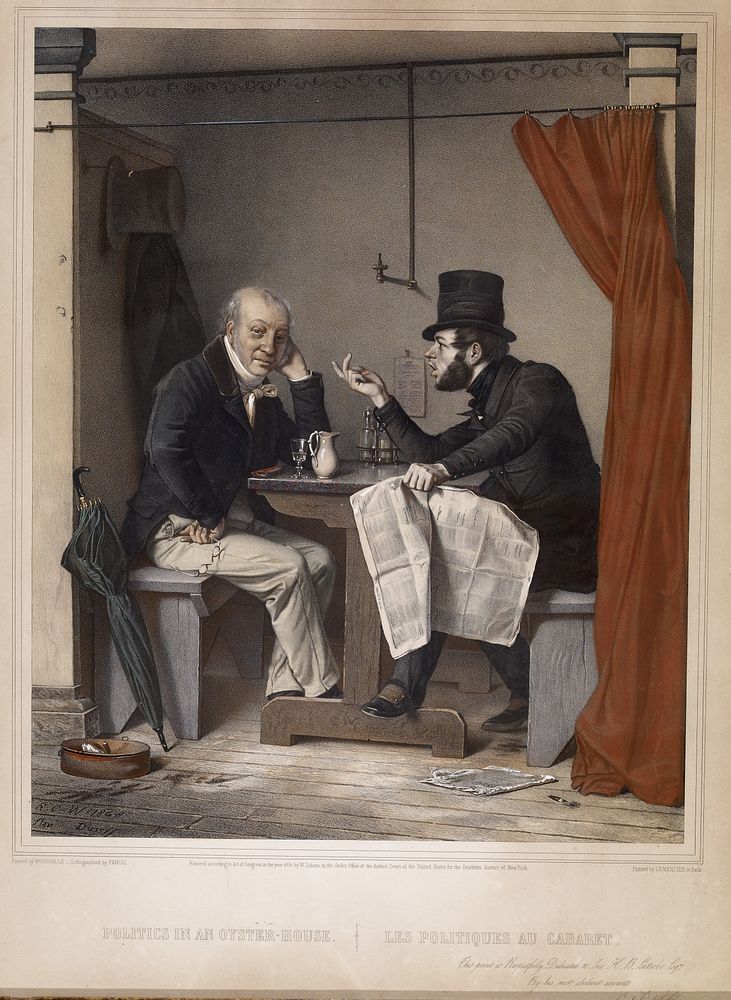

Image Via: Rawpixel

3 comments

ND

Regarding Christian “politics”, a politics of “civility , of charity, and of friendship, and Healthcare that is Life-affirming and Life-sustaining and thus serves for The Common Good:

https://www.chausa.org/publications/health-progress/archive/article/may-june-1999/the-common-good-and-healthcare-policy

https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/yale-scientists-link-post-covid-jab-illness-to-biomarkers-that-include-elevated-spike-protein/

Nancy

Sort of off topic but consistent with hoping for the best for all persons:

https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/yale-scientists-link-post-covid-jab-illness-to-biomarkers-that-include-elevated-spike-protein/

ND

“Is a Christian politics of love possible? “

I suppose the question is, is the essence of Love grounded in politics, or is it grounded in respect for the inherent personal and relational Dignity of the persons existing in a relationship of Love?

No doubt, those who are seeking the destruction of the Family, because they desire to render onto Caesar what belongs to God, The Ordered Communion Of Perfect Complementary Love, The Most Holy And Undivided Blessed Trinity, Through The Unity Of The Holy Ghost, The Author Of Love, Of Life, And Of Marriage, and thus The Author of our unalienable inherent Right to Life, to Liberty, and to The Pursuit of Happiness, the purpose of which can only be, what God, Who Is Perfect Life-affirming and Life-sustaining Love, intended,

having created a politics that is anti Christ, and thus anti Love, are certainly not are friends. This does not change the fact that to Love one’s enemy is to continue to desire their Salvation, and in that, there is no contradiction.

At the heart of Liberty Is Christ, “4For it is impossible for those who were once illuminated, have tasted also the heavenly gift and were made partakers of the Holy Ghost, 5Have moreover tasted the good word of God and the powers of the world to come…”, to not believe that Christ’s Sacrifice On The Cross will lead us to Salvation, but we must desire forgiveness for our sins, and accept Salvational Love, God’s Gift Of Grace And Mercy; believe in The Power And The Glory Of Salvation Love, and rejoice in the fact that No Greater Love Is There Than This, To Desire Salvation For One’s Beloved.

“Hail The Cross, Our Only Hope.”

“It Has Always Been About The Marriage In Heaven And On Earth.

“Blessed are they who are Called to The Marriage Supper Of The Lamb.”

“For where your treasure is there will your heart be also.”

Comments are closed.