America has a crisis of friendship, one visible in the decline of close friends, increasing levels of loneliness, and waning participation in clubs and associations. In our search for solutions, we might find unexpected guidance in Thomas Hughes’s Victorian novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857). Published during the golden period of economic prosperity that emerged two decades into Queen Victoria’s 63-year reign, Tom Brown’s Schooldays is concomitantly a work of socio-political thought and a contribution to the history of education. It is also what its author Thomas Hughes (1822–1896) intended it to be–namely, “a real novel for boys…written in the right spirit but distinctly aiming at being interesting.”

Its setting is England’s storied Rugby School in the 1830s. It is a semi-autobiographical work, providing a fictionalized account of Hughes’s own experience as a student under the governance of legendary headmaster Doctor Thomas Arnold (1795–1842). This novel offers an enlightening lesson on the nature of friendship and its role in constituting civil order. Most significantly, it reveals ways in which intrinsic bonds such as friendship comprise the very substance of regimes. This lesson is particularly vital in our own age, where egoism prevails and rationalism crowds out custom and tradition.

Great works of literary art educate forcefully and unforgettably. Indeed, depictions of the principles of human community are as ubiquitous in novels, drama, poetry, and myth as they are in political philosophy, which addresses foundational questions of the nature of human coexistence. Apart from direct experience with other people whose qualitative individuality and difference from us is of paramount importance, the literary arts offer the most impressive guides to the contours of coexistence and the complexities of culture and politics.

There is, for instance, perhaps no clearer depiction of what is at stake concerning the tension between duty to kith and kin and obedience to the political prerogatives of the sovereign and of law than the dreadful contest between Antigone and King Creon of Thebes in Sophocles’ great tragedy. The travails of King Lear portrayed vividly in Shakespeare’s blank verse admonish us to appreciate that the intrinsic bonds of family, friendship, and love are themselves the foundation of kingdoms. John Milton’s Paradise Lost sharpens our understanding of the relations linking freedom, responsibility, and authority. In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the brothers Alyosha and Ivan examine and ponder the nature of justice and the burden of brotherly love, and, once they have argued their cases, we the readers are never the same.

The literary arts deepen our comprehension of human coexistence whilst broadening our horizons concerning what is possible. From this view, Leo Strauss’s dictum, “The proper form of presenting political philosophy is the treatise,” appears misguided insofar as the love of wisdom concerning human things may be the object of moving imagery and dramatic tension as well as of reason. (Strauss the Platonist certainly understood this.) While theoretical treatises illuminate abstract rational principles, great works of literature show us how real order arises from bonds formed between distinct personalities achieving concord in their differences. Such literature instructs wisely concerning how man does live and, perhaps, how man ought to live.

This brings us to the lessons of Tom Brown’s Schooldays.

The abstract notions of friendship and civil order come to life in Hughes’s novel. The protagonist is the eponymous Tom Brown, a boy whose vigor and physical energy represent the image of youth. Tom’s parents have sent him to Rugby for an education, and the reader immediately learns that education is not simply curricular. Tom finds pleasure in “going round to the studies of all his acquaintance, sparring or gossiping in the hall, now jumping the old iron bound tables, or carving a bit of his name on them, then joining in some chorus of merry voices; in fact, blowing off his steam, as we should now call it.” During the day, he suffers his lessons in Latin and Greek.

Tom’s foil is George Arthur. George is a boy from a lower grade who begins as Tom’s charge and later becomes his friend. George embodies reason and achievement. He is given to sincere study and to quiet contemplation.

Rugby’s headmaster, Doctor Arnold, pairs up these two boys. In doing so, he creates conditions for friendship and the rudiments of civil order–both Rugby’s and England’s. Friendship is a substantive state, one that emerges from the immediate interaction of human wills and engenders concord. By concord I mean both an observable harmony between persons and the organizing principle that brings about such harmony. Friends are unified: their hearts joined, and their burdens shared. In their interaction and mutual experience Tom and George give rise to concord, and this serves both their friendship and their individual flourishing.

This may be stated more strongly. The emergent friendship itself conditions and affords the realization of each boy’s own nature. It offers each one a new potential by setting new bounds of experience. It does so whilst laying the foundation of civil order grounded on their actual, historical patterns of coexistence and bonds with one another.

In the passage in which Tom and George first meet, the contrast between these two boys could not be more marked. Tom has just returned from a visit to the Spread Eagle coaching house. He and his friends have just “rushed into the matron’s room in high spirits, such as all real boys are in when they first get back.” Immediately before bounding out of the room, Tom is alerted to George’s presence: “He looked across the room, and in the far corner of the sofa was aware of a slight pale boy, with large blue eyes and light fair hair, who seemed ready to shrink through the floor.” Tom recognizes that George would be miserable were he left alone.

Doctor Arnold places George under Tom’s charge. During George’s first night at Rugby he asks Tom for permission to wash up, and he then steals “timidly from between the beds out to the wash-hand stand, and [begins] his ablutions.” George emerges from a place where he is shielded and does so under the care of the watchful Tom. This moment prefigures George’s moral growth as he learns the ways and customs of Rugby by participating in them, integrates with his classmates as they impart tradition, and contributes his share to their life in common.

To see how friendship emerges, let us consider the two boys’ influence on one another during the classic Rugby act of doing “vulguses” (i.e. completing Latin verse composition homework). It is here that we see the value of human difference and complementarity.

Hughes writes, “Tom was the upholder of the traditionary method of vulgus doing. He carefully produced two large vulgus-books, and began diving into them, and picking out a line here…[proceeding] to patch his tags together…producing an incongruous and feeble result.” The method used by Tom mirrors his spirited approach: diving, picking, and patching. The traditionary method is familiar to all Rugby boys, “such boys as our hero, who has nothing whatever remarkable about him except excess of boyishness; by which I mean animal life in its fullest measure.” Hughes’s reference to Tom’s feeble result impugns the approach–and we recall that Tom is the fictionalized Thomas Hughes himself commenting retrospectively.

This passage sets up the approving description of George’s method:

The artistic method, was George’s. He considered first what point in the character or event which was the subject could most neatly be brought out within the limits of a vulgus, trying always to get his idea into eight lines, but not binding himself to ten or even twelve lines if he couldn’t do this. He then set to work…to clothe his idea in appropriate Latin or Greek, and would not be satisfied till he had polished it well up with the aptest and most poetic words and phrases he could get at.

George neatly construes his idea, composes it with integrity, and demonstrates how reason channels passion.

It is in following the progress of these two boys that man’s relational nature is brought to the foreground along with a demonstration as to how man’s relations condition his flourishing and provide order. The narrative presents the knowledge of this in a way that is difficult to communicate in the form of a political treatise. To wit, George grows very ill at one point, and, following his recovery, George asks Tom to reflect on what he wants to take from Rugby. Among Tom’s list is to “please the Doctor” and “carry away as much Latin and Greek as will take me through Oxford.” Tom’s traditionary method of doing his vulguses is doing little for his individual growth. George underscores this for Tom, and Tom works on becoming a better student. Tom comes to appreciate George’s perspective, learning by seeing through the eyes of his friend.

Tom’s and George’s friendship throws into sharp relief ways in which nature and convention are interlaced dimensions of real coexistence. Through their daily interactions at Rugby, Tom retains his spirited nature while gaining thoughtfulness. George preserves his contemplative character while developing vigor. Their friendship creates conditions where each finds fuller expression through a shared participation in shaping one another and Rugby’s civil order.

Neither nature nor convention can be taught or ordered rationally. The natural endowments of Rugby boys must be intermixed with customs, traditions, and novel emergences that are created in and imparted through practice and in experience with others. It is from these elements and the intrinsic bonds to which they give rise that civil order arises.

The pedagogical value of this insight undoubtedly was clear to Doctor Arnold, who was forming Rugby boys as well as Englishmen (Hughes, for example, went on to became a member of Parliament). Arnold is renowned for having transformed Rugby during his tenure as headmaster. His institution of practices of self-government and administration of domestic life was quite influential. He also established a curriculum providing a classical education that elevated Rugby boys above their parochial interests. Under his headmastership, Rugby became the model English public school.

Doctor Arnold set up a situation in which the boys–because of their differences–complement one another and thrive. Their relationship placed limits on the individual selves whilst directing these selves to a realm of possibility constituted by bonds with others. Tom matures in the company of George by adopting a respect for sincere achievement. George emerges into a world in which he stands his ground. Later in the novel, George finds his scholarly interests are valued and his resulting enjoyments in the playing fields makes clear that he is taking on the shape of a Rugby boy. The boys’ roles as one another’s educator were mutual and the effect that they had in shaping the moral and social order at Rugby was not a theoretical exercise but a product of real coexistence.

Here I have offered only a glimpse into Tom Brown’s Schooldays. There are several other narrative arcs throughout the novel that reveal Thomas Hughes’s incisive insight into the relation between friendship and civil order. Among them is a gripping account of a fist fight that raises questions about honor and justice. There is also a colorful and intricate depiction of a Rugby football match wherein the reader observes that the rules of Rugby football are both customary and yet revised by the actual boys playing on the field. The rules and technique of play are a property of Rugby boys–a property in the strongest sense of an accumulation of doing, practicing, and making that is a constituent of oneself.

Through their interaction and due to their differences Tom and George lay the groundwork of a civil order the form of which is an actual historical creation that bears their imprints. The ties that bind them are immediately grounded products of their mutual experience. George relies upon Tom for knowledge about Rugby’s customs and traditions. Tom steers George from becoming like the “miserable little pretty white-handed curly-headed boys, petted and pampered by some of the big fellows, who…did all they could to spoil them for everything in this world and next.” Tom’s supervision of George offers him a practical lesson in moral guidance and allows him to embody the aim of Arnold’s pedagogical experiment as headmaster: changing the contours of civil order at Rugby without destroying what is good about Rugby qua Rugby.

The novel’s major pedagogical insight is that pupils are always educated alongside particular individuals and in particular places and at particular times. Such insight can be grasped only loosely in a treatise focusing on abstract notions. Civil order is primarily immediate, local, and rooted in concrete historical experience. Doctor Arnold’s inspired pairing of these two boys demonstrates that civil order need not stand in tension with personal bonds. Rather, the immediate interaction of distinct personalities within a context that permits their mutual development may give rise to both individual flourishing and collective harmony. In reading Tom Brown’s Schooldays we are reminded that concord achieved between different yet complementary human wills is a substantive reality–the very substance of civil order.

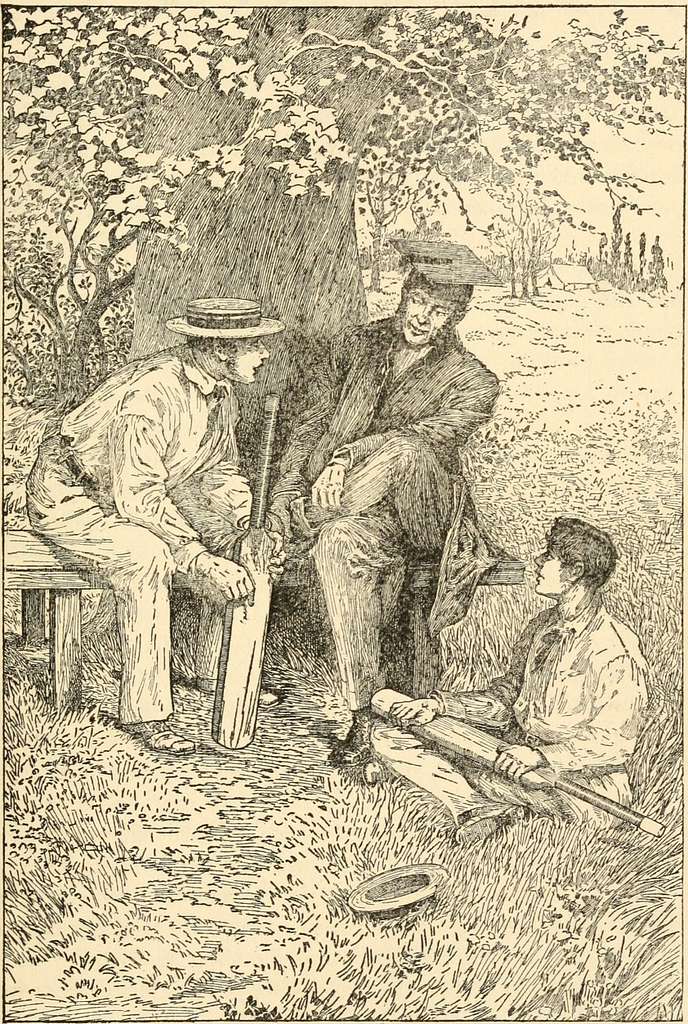

Image Via: PICRYL