When Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind first appeared in 1987, perhaps the most controversial argument in that highly provocative book was Bloom’s sustained attack on rock music. In a chapter tersely entitled “Music,” Bloom argues that the music of young people, by which he largely meant rock music, constituted a vulgar appeal to the emotions, stirring up souls into a chaotic frenzy. In such a maniacal state, the psyche is ripe for revolutionary thinking and the soul becomes accustomed to lowbrow music at the expense of appreciation for beauty.

Bloom drew upon the ancient teaching, most directly addressed in Plato’s Republic, that music has the power to subtly construct the architecture of our psyches, thus we should take music seriously. Carson Holloway would later make a similar argument in his book All Shook Up: Music, Passion, and Politics. As Holloway argued, it is not the lyrics but the form of music–what we might call genre, although that’s not quite the same thing—that is important. The effect of music is produced through melody, rhythm, arrangement and the like that hits us at a visceral level.

Bloom’s contentious assertion that rock is a degenerate form of music caused a stir precisely because music was something people cared about deeply. I am of an age that I could have been among Bloom’s last students (although I did not have the privilege, nor the smarts, to go to Bloom’s University of Chicago). I know how important music was to my classmates in high school and college. If you criticized someone’s music, you were hitting them where it hurts.

As long as I can remember, music, largely popular music, has been very important in my life. Collecting and listening to music was long my major avocation, along with hoarding books. That has slowed down in the age of job, wife, and kids as I no longer have much time to just sit and listen to an album from beginning to end. And spending money on music seems like a frivolous expense on an inevitably tight budget. Still, not a day goes by when I am not listening to something.

In my youth, like most of my generation, I was influenced by my parents’ tastes. In the case of my mother, that was 1950s rock and roll. The seminal album of my youth was the soundtrack to American Graffiti. There was also Elvis Pressly, The Everly Brothers, and Buddy Holly. My father listened to country radio. As a teenager I walked away from such music only to rediscover it in my twenties, with a special interest in what we call “traditional” country music. Now my favorite recording artist of all time is Merle Haggard. In my teen years, able to afford my own radio and stereo equipment, I obsessed on music from the 1960s. I was a latter-day Beatlemaniac. I listened to oldies radio religiously. I discovered The Who, Lovin’ Spoonful, The Turtles, The Byrds, and, in a fit of nostalgia about the old TV show, The Monkees. I did also listen to pop radio, with Casey Kassem’s American Top 40 being a weekly ritual through most of my high school days.

In college there were albums that everyone “had to have.” In those days, greatest hits collections from Steve Miller and The Eagles were must-owns. This is also when Tom Petty’s Full Moon Fever album came out. You weren’t even in the conversation if you didn’t have that album.

While I might have been more passionate than most, the difference was a matter of degree not kind. Most college students had strong musical tastes. I once listened to the Beach Boys Pet Sounds album for six straight hours. I went to college with a guy who watched the Led Zepplin rockumentary The Song Remains the Same every week. This is the guy who once streaked across the football field during a game, so that tells you something about him.

One thing I have noticed about my own students is a distinct lack of passion concerning music. When I first started teaching, at Christmas time I would give a small amount of extra credit on a quiz if a student simply listed a favorite Christmas song. I would then give bonus credit if the student was willing to sing a verse in front of class. After a few years I noticed how many students struggled to come up with a song. This was shocking to me as I also have strong opinions on Christmas music. How can you not have a favorite Christmas song? Or strain to even name one beyond “Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer”?

Today I have few students for whom music is as important as it was to a typical student in my own college days. Interestingly, students who do have some passion for music typically enjoy older music more than contemporary popular music. YouTube musicologist Rick Beato argues that it may be the sad state of today’s popular music that is to blame the weak attachment to music among today’s young people. Beato asserts current music tends to be corporatized, too dependent on technology rather than musical talent, and relatively bland and flat. It just doesn’t speak to the soul. Just give a listen to the latest release from megastar Taylor Swift if you want an example of banal, lifeless pop music.

Surely changes in the music industry and technology have something to do with this soullessness. Beato makes such a suggestion here, as does Ted Goia. In a Spotify world, it is easy to simply listen to tracks we already like. The algorithm tends to feed us more and more of the same thing, losing that serendipitous discovery of the new song. Such a discovery was normally from the radio, which is largely dead. I suspect none of my students get their music from the radio. To the extent they listen to music it is on streaming services like Spotify or via YouTube. They listen track by track, not album by album, and let the algorithm choose their music for them.

But something has happened to young people’s souls. Is this part and parcel of the anxiety, distraction, the acedia of modern life? Have their souls simply been flattened by smartphone distraction and bland corporate music? I believe that if I worked through Bloom’s book with today’s students, they would find the chapter on music not infuriating but baffling. Why would anyone care so much about music?

Bloom and Holloway worry about young people’s souls getting a deficient musical education as that is tantamount to getting a deficient education of the soul. What if the problem is not bad education, but no education? Not overly passionate souls, but dead souls. As C.S. Lewis noted in The Abolition of Man, the souls of our youth are not jungles that need pruning but deserts that need irrigation. We could start by getting them to hear music.

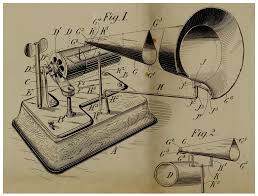

Image via Flickr

5 comments

WB

How can you be moved by music that’s been flattened, squeezed, and left with no dynamic range? Modern music and they way we listen to it is mostly just noise. I love to listen to Beato analyze what makes certain songs great, though you’ll be hard pressed to ever get the clarity from the radio or streaming service. Streaming killed the radio star…

Rob G

I read something recently which said that while young people consume a lot of music, as evinced by their use of Spotify, etc., that doesn’t mean they really listen to it. As you say, it serves as background or wallpaper, thus they seem to like music that doesn’t require a lot of attention, but can simply create or enhance a mood. Even among some of the younger people I know who seem to really “be into” music, one gets the sense that their appreciation is mostly wide as opposed to deep.

Jon Schaff

Adam,

Thanks for the kind words. Swift is a strange phenomenon. She is so popular that her tour has had measurable economic impact on the nation. Yet, her music has had little cultural impact. Although I have listened to some of her music, I struggle to name a single song of hers. I am nowhere near her demographic, still I suspect that is the same for most people. They know who Taylor Swift is without knowing any of her music. She doesn’t have single song that “everybody knows” (such as Hound Dog, or Yesterday, or Satisfaction, or I’m a Believer, or Hotel California). While excitement over pop stars is quite typically due to their celebrity status rather than musical quality, still, Swift seams more than usual simply a marketing phenomenon rather than a musical one.

Rob G

Swift strikes me as similar to Madonna or even the Spice Girls in terms of appeal, but with more substance and a (somewhat) more “wholesome” quality. She’s like one of the giant country stars, but one who’s doing pop instead of country and thus gets much broader attention.

Adam Smith

I’m glad to see you writing about this, Jon. I’ve noticed the same thing in my students. You can’t even get to the point of grappling with an argument like Bloom’s about what music should move them; they don’t seem terribly moved by any music, which they do listen to, but more as a background, or as a tool to get themselves into a certain mood. They rarely seem to care about music itself.

The Taylor Swift example is interesting, though, since Swift has a famously passionate fan base, and is furthermore apparently one of the only musicians who has resisted the algorithmic fracturing of the listening public into smaller and smaller micro-cultures.

Comments are closed.