AI is reshaping the landscape of higher education. AI enthusiasts rave about the possibilities and the positive transformations to come, but realists are already in despair about how little work students are doing. The ease and accessibility of AI tools mean that students are constantly presented with the opportunity to have unearned good grades. The challenge exceeds the marshmallow test, because students may resist the temptation and then receive lower grades than their peers who do use AI.

As AI tears through campuses, students make hard choices. Unauthorized AI use is academic dishonesty, like plagiarism. Students who use ChatGPT to do all their work are being shortchanged the education they are paying for. Students might consider that AI use could hurt their employment prospects. Not all job qualifications can be made up for by being very good at AI queries. Of course, using AI without permission and taking credit for work one does not do also contributes to ethical erosion. On the other hand, when they are behind on work, or worried about their GPA, or imitating their more successful peers…

The situation presents a real dilemma for students. And because AI detection is still imperfect, the potential reward seems to outweigh the risks. (Students seem less informed about ChatGPT’s flaws, like creating sources out of thin air, and unaware that many professors do not prefer papers written by AI.) As students weigh their decision about AI use, they consider how it might affect them personally. What students do not know or consider is that the threat and use of AI has also initiated them into something of a “prisoner’s dilemma.”

In the classic prisoner’s dilemma scenario, two prisoners are choosing whether to cooperate with each other or the authorities. The prisoners are separated and interrogated by the police. The police are offering a deal to whoever will cooperate with them first and testify against the other. If both do not cooperate with the authorities, both will gain. If one betrays the other and cooperates with the authorities, only the betrayer will gain. If both betray each other, both lose. When a student makes a decision about using AI without permission, they may think they are playing individually against the system, but they are actually in something of a prisoner’s dilemma.

The reality is already playing out across the country. Consider a required, introductory mathematics course, designed for non-majors. It is a class taken by people who do not like math or want much to do with it. The textbook and the homework assignments are all integrated online. Homework is weighted fairly heavily, so that high pressure assignments like tests are important but not everything. Students get credit for doing the work and making progress. Students can work independently and access the materials and practice quizzes anywhere, at any time. Pedagogically, this is an ideal approach for a course like this. Practically, it will seem impossibly utopic within two years.

By now, students have realized that they can complete all online or remote work by using AI tools. They can easily achieve perfect scores on every homework assignment and on practice quizzes, projects, etc. They cannot pass any of the tests this way, but the tests are not the only things that count, because it is a class designed to reward people for doing the work and learning. Unfortunately, now students can pass the class without learning anything. Many do. This group of students has essentially, if accidentally, betrayed their peers.

An introductory course like that may be the most obviously affected, but it is not the only course affected. There are any number of courses where tests are not considered the best measure of learning outcomes—like those which rely on papers. Not every class has everything online, but academic publishers and university bookstores have been pushing for years to make as much of the curriculum online as possible.

AI use will deprioritize pedagogy. What will that mathematics course, and many others, look like next year? The tests will count for much more than anything else, making the higher intensity assignments also very high stakes. Homework will count for little or nothing. There will likely be quizzes on the homework. More required assignments will be done by hand. A class which was designed for people who could use assistance with math will be much harder, and will do nothing to help people warm to math. This scenario applies to almost every class.

Rampant unauthorized use of AI means that classes will have to be restructured—with a primary goal of ensuring honest work rather than encouraging learning. The points you can earn working independently, at your own pace or in your own space, making gradual consistent progress—they will cease to count for much or to exist at all, in almost every class. The amount of testing will increase. The amount of writing by hand will increase. This is the only way to guarantee authentic work.

Despite the promises of enthusiasts, AI will not make everything easier—in education, it will make many things harder. It will become more difficult for unexceptional and underprepared students to excel. We can expect inequalities to be exacerbated, not eliminated. Rather than becoming worth less, the college degree might be worth more, but it will be considerably less accessible and harder to earn. The promise of AI is utopian and seems futuristic, but its effects on the educational landscape will make students nostalgic for the pre-ChatGPT days of yore.

Perhaps all of life is something of an unwitting prisoner’s dilemma. We make decisions independently without realizing the extent to which we affect others, or without realizing the ways in which others are affecting us. When it comes to AI use as a prisoner’s dilemma, students have a limited ability to make informed, ethical choices because they are not informed. We do very little to explain education and educational systems to young people. Students should know that this “great leap forward” has thrown them unwittingly into an example of game theory. They should know that their choices do not result in independent actions on a fixed map. Their choices also change the terrain, for everyone.

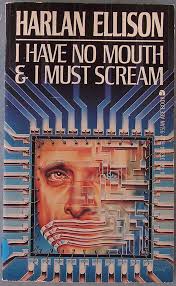

Image via Flickr

3 comments

David Naas

Not AM or Skynet, Not R.U.R. revolting. Not Doctor Frankenstein’s Monster…

We don’t require a malevolent construction. We have our own sloth.

Pertinent to the illustration:

“AM has altered me for his own peace of mind, I suppose. He doesn’t want me to run at full speed into a computer bank and smash my skull. Or hold my breath till I faint. Or cut my throat on a rusted sheet of metal. There are reflective surfaces down here. I will describe myself as I see myself:

I am a great soft jelly thing. Smoothly rounded, with no mouth, with pulsing white holes filled by fog where my eyes used to be. Rubbery appendages that were once my arms; bulks rounding down into legless humps of soft slippery matter. I leave a moist trail when I move. Blotches of diseased, evil gray come and go on my surface, as though light is being beamed from within.

Outwardly: dumbly, I shamble about, a thing that could never have been known as human, a thing whose shape is so alien a travesty that humanity becomes more obscene for the vague resemblance.

Inwardly: alone. Here. Living under the land, under the sea, in the belly of AM, whom we created because our time was badly spent and we must have known unconsciously that he could do it better. At least the four of them are safe at last.

AM will be all the madder for that. It makes me a little happier. And yet AM has won, simply he has taken his revenge.

I have no mouth. And I must scream.”

Jonathan F.

I would suggest that the logical consequences you see unfolding are evidence that we’ve made too many people “students”. Do “unexceptional and underprepared” students really “excel” now? The unprepared with the desire and will to gain what they’ve realized they missed out on are the exceptional ones; the unexceptional will only even meet standards – if we’re honest about the standards – if they’re already well-prepared.

I think you’re entirely correct, that if we take the necessary steps to make sure students do their own work, by necessity standards for that work will have to be tightened up. To me, that seems entirely desirable. But my suspicion is that we have no interest, as a culture in general, in tightening standards, and any attempts to limit AI use will remain half-hearted at best in most schools.

Aaron

Good article, Elizabeth. These are exactly the sorts of issues I’ve been thinking about in my own classes. Since we’re both in history, I’d be interested in following up a bit. I have a feeling that there may be some silver linings for gen-ed level history classes, aimed at the sorts of students in your math example.

Aaron

Comments are closed.