A new year. New opportunities. As a professor, the turn of the year means new students, new schedules, and new lectures. With all these changes, not much is certain. But I’m confident in one thing for the spring semester: conversations about AI will rage. I have little interest, or expertise, in evaluating the latest developments. I do have concern, though. Maybe more than concern. Maybe something more like a pebble in the heel of my shoe.

Such scruples reassert themselves in every conversation about or advertisement for AI that boils down to the value of efficiency. It is difficult to make a rational argument against the benefits of efficiency. Instead, this year, I want to live a cheerful life that embodies praise for the inefficient. I choose to celebrate what’s not streamlined and commoditized. I hope to revel in something that’s not urgent, not immediately profitable. What follows is not a system, a plan, or a strategy. It’s a litany of the goods I want to praise.

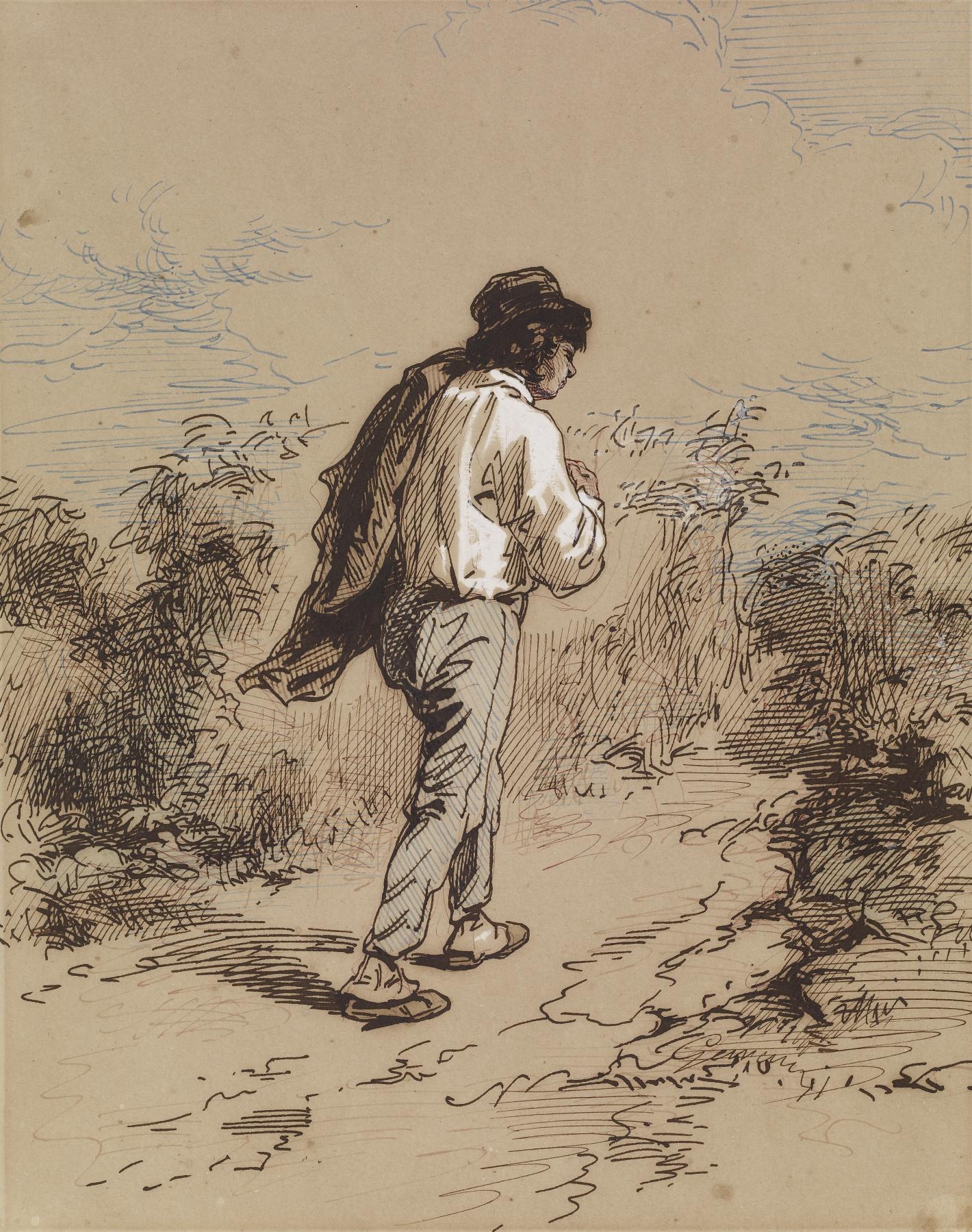

Walking. This little miracle. The wonder parents have in watching a toddler transition from toddling to, well, walking. This act as an adult seems outdated, superfluous, and at times, pitied. I have the odd opportunity of living on the same property as I work (a seminary). Walking to work, which is a short and typically hot stroll (New Orleans, LA), I’m passed by cars, trucks, cycles, golf carts, and hoverboards. I hold no condescension—well, maybe a little for golf carts, if I’m honest.

I haven’t always travelled as an unaided biped on this little commute. I would at times cycle or drive, knowing I would save roughly seven minutes of work time. An organized, planned, and well-executed start to work would infuse my day with the imagined grace of productivity. ‘Getting stuff done,’ I’d say to myself. But in hearing the current calls by marketers and influencers for more productivity, quicker, faster, more, more, more, I’m choosing not to listen. I’m holding my hands over my ears. This year, I walk. And not just for health, for steps, or for stats. But because I can. Because I can throw away, waste, and mismanage those minutes that could be squeezed for a more productive morning. I want to bask in the glory of the pedestrian.

Praise

Reading. Too many times someone has told me they’re listening to an audiobook. I love all things audio. Music, books, podcasts, the whole lot. No qualms here. But when they tell me they’re listening to it at 1.5 speed, sometimes 2x, I struggle. The reading is becoming one more consumptive practice to maximize. The beauty of words is lost in this rushed aural activity. But still it’s complicated for me. As a professor of Old Testament, I frequently try to get students to lift their eyes and ears and listen to the public reading of Scripture. Listen but not read. I want to help them connect their ears to their mind in a way that has historical precedent—and purchase.

While I won’t change this classroom practice, I am redoubling my efforts to both show and tell the beauty and wonder of slow, active, long reading. No summaries, no reviews, no scanning. If the writing is worth reading, then I want to tuck in. Forget the to-do list. I want to do something that the hurried, the harried, the thought-to-be successful don’t do. I want to read for long and glorious hours. Reading as a joy. A protest to productivity.

Praise

Poetry. Hardly anything is more economical and yet more inefficient. Poetry’s ability to fold layers of meaning into a few words and then unfurl them in affection and delight. Poetry is music and memory; it’s meaning without simple morals. Joy. I cannot imagine that someone who gravitates to self-help, scours the internet for life-hacks, and constantly thinks about how to streamline their day, week, and year also reads poetry.

Poetry, at least good poetry, can’t be commodified. I want to read more of it. Yes, the Bible’s poetry (the Psalms, the Song of Songs, Isaiah, and more). But also, Herbert, Donne, Hopkins, Oliver, Berry, Stallings, and more. Not just read, though. I want to inhabit the poems; memorize them. How inefficient!

Praise

Language. Living in the United States, I feel like I have to defend myself for wanting to learn other languages. ‘Why bother?’ the question goes, and usually with a little dose of disdain. In part, it’s my job. As an Old Testament prof, I teach ancient Hebrew. To be at least half-decent at my work I have to have some sense of several ancient languages and a few modern ones. I’m fairly practiced at deflecting irritating questions about language learning, as well as defending the significance of my vocation. But now, with translation technologies getting better and more accessible, these questions are cropping up more and more. And with more intensity. ‘Why are you wasting your time?’ ‘Programs can do this for you!’ ‘You don’t need to know the grammar or the vocab.’ Just plug-and-play.

While I’ll have some retorts for those who ask these questions, my primary response this year is a bit different. I’m going all the more to un-Englished sources. Give me Bonhoeffer sans the translation. Give me Goethe without the gloss. Give me Augustine without English annotation. Make me work. Make me strive. Make me produce a translation that’s worse than a hundred already published ones. Such inefficiencies. Such delight.

Praise

Prayer. Maybe the most well-known and least practiced spiritual discipline. Sure, it’s confusing. It clearly needed to be taught to the disciples. It’s boring, too. And unproductive. Honestly, what’s the return-on-investment? Not good. Some Christians forgo prayer because they assume God doesn’t care. Others stick to the ‘God’s gonna do what God’s gonna do’ strategy. Both end up in the same place. A prayer-less life filled with self-reliance. In avoiding the theologically anemic positions, I’m still not interested in putting prayer on the productivity scale.

This year I’m knowingly diving into this inefficient Christian practice. Not because I feel guilty. Not because I read a biography of some saint who prayed three hours before doing anything. But because it’s good. Because I can’t quantify its qualities. So I’m taking the Psalms, the Church Fathers, the Reformers, and more and reading their prayers. Praying their prayers. Being taught the slow art of speaking to and hearing from God. A practice that has no cultural cachet, even among Christians. This practice of prayer, for me, will have no time sheet, no schedule, no specific expectations. I’m just going to pray. Pray in a way that’s untethered to accomplishment and unhinged from any satisfaction of production. The joy of communing with God.

Praise

Fatherhood. My sons (9 and 3) are fascinating and unproductive creatures. Unproductive not in the sense of laziness, but in the strict sense of not trying to be productive on a day-to-day basis. They have no real standard they are striving to achieve. So, by necessity, they’re rarely efficient in the unimaginative ‘grown-up’ world that I tend to inhabit. Their industriousness, however, comes in their play. Worlds are conjured up with their words. Stories are told while holding toys. Plots, twists, complicated and improvised backstories are all part of their narrative craft. Nothing is off limits to their ambling. If the activity is about timely accomplishment, taking them to the aquarium is an exercise in futility. The long wonderment at God’s creatures brings a stillness to my lads that is equally stunning and vexing to their father.

This year there’s a concerted effort to include the boys in many of our routine tasks. Breakfast has become the laboratory. My three-year-old whisks the eggs with joy, and my nine-year-old cooks the bacon with the attention and pride of a skilled painter studying a canvas. Could I do it all faster? Yes, indeed. Am I doing this to help my sons learn to navigate the kitchen specifically and responsibilities in general? Again, yes. But not just that. I want to venerate the meandering and very much non-silent act of cooking with my boys. Inefficient as it is loud. And oh, how I love a quiet morning.

Praise

Writing. I love sentences. I used to be quiet about this deep-seated affection. No more. With only a smidge of an opening, I’ll burst through a conversation and declare my love of the sentence. Well-curated advertisements tell of how the latest technology will help writers. Human scribes of emails, texts, and papers should have no fear: their errors and infelicities will be improved by a machine. ‘Rest easy,’ they say. But higher education is not resting easy. Not even a little. Plagiarism policies and counter-technologies are rolled out as quickly as possible. So it is.

But this year I’m renewing my commitment to the sentence. None shall separate us. I want to lavish in the fact that I’ll rewrite one sentence eight times. That I’ll re-read a chapter for my next book over fifty times. I’ll read it backwards. I’ll read it on printed paper, on a screen, zoomed in, zoomed out. Aloud. Silently. Any way that I can see it differently. It’s not efficient. When I return home for lunch and my wife asks, ‘What did you do this morning?’ I’ll answer with the joy of unproductivity: ‘I read my chapter three times.’ ‘Is it finished?’ she’ll ask out of kindness. ‘No, but it’s closer,’ I’ll respond, with a smile.

So this year, I’ll write. I’ll write books that have contracts, poems that no one will see, articles for a handful of specialist academics. I’ll write. I’ll rewrite, second guess, delete, rephrase, re-start, and do it all over again. And to the ministers of efficiency I say, ‘Convince who you will; plunder and pillage in the name of productivity!’ But as for me, I’ll do something so basic and so seemingly banal, but so blatantly beautiful: I’ll craft a sentence that I love. A sentence with no so-called intelligent assistant to shape my syntax or my style.

Praise

Thus is my protest of the quick, the easy, the effortless. This year, may I be a little less useful. May my habits make me saunter.

Praise

Image: Man Walking Paul Gavarni