As Caleb has already noted here, Rusty Reno and Jody Bottum have been mixing it up over at First Things over issues of localism, a hot topic of late on the internets, it would seem. Rusty asserts that “patriotism is the political form of love,” and concludes, with the faith of true love, that “I’ll take the blind love and I’ll try to correct its faults” (this line of argument recalls an instructive review of Walter Berns’s Making Patriots by Bill McClay some years back in Public Interest – well worth the read). Rusty acknowledges that love of the local always involves preference for one’s own. He raises the difficult question whether such love of one’s own can be held in ways that are not hostile or destructive toward that which is outside that circle. It’s a legitimate question that must be confronted and explored, but – Rusty concludes – not at the expense of dismissing thick commitments to one’s own.

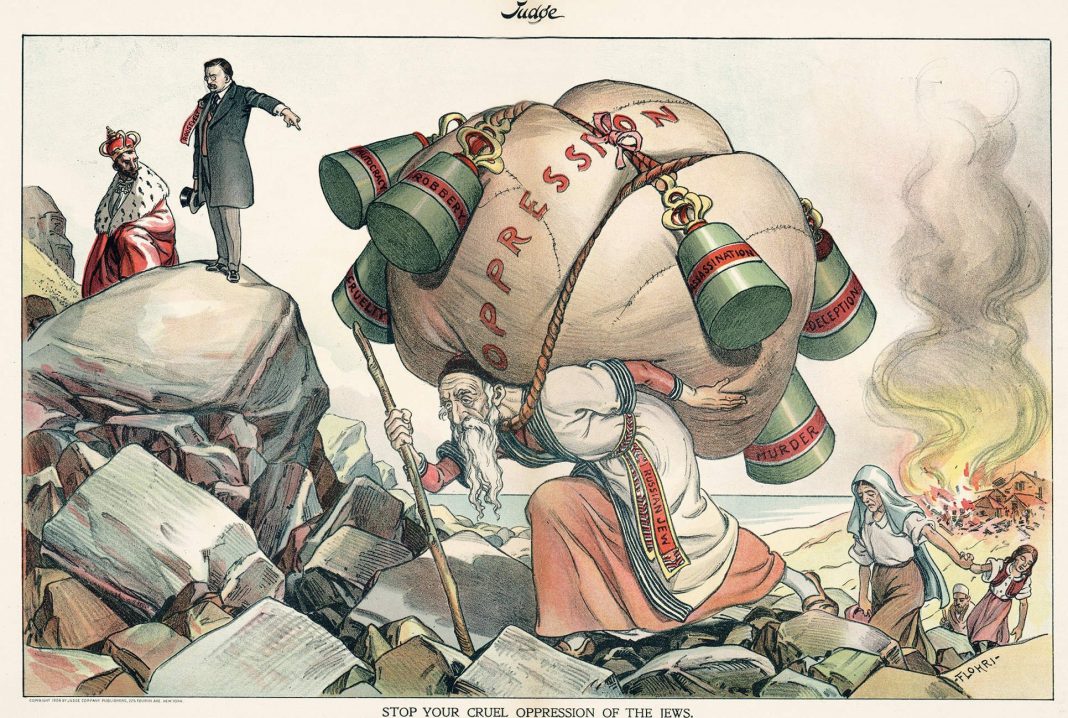

Jody brings in the big guns with suggestions that any defense of local community inevitably invites a trajectory toward anti-Semitism. Jody’s response is, for lack of better pigeonholing, the classic liberal move: insinuate the anti-Semitic (or racial, or sexist) designs of localists, and thereby render the whole argument suspect and vaguely disreputable (for another example, see Louis Menand’s treatment of Christopher Lasch in his book American Studies, which saves the shiv for the end, rather than as the main attraction). Russell Arben Fox and I had that move made on us some years back on a panel where we jointly appeared at which we made various cases for democratic populism.

The charge, or even intimation, of anti-Semitism (or sexism or racism or homophobism) is invoked at such moments to be a conversation-stopper. At that point, the discussion will, more likely than not, devolve into a back and forth in which one party says “No, I’m not,” and the other says, “But people like you always are.”

Jody raised the issue of the Jews in the first instance because they seem to be the exception that proves the rule: given the treatment of Jews by local communities, we can conclude that by nature local communities persecute minorities. Caleb has already answered this charge far more ably than I can, but I agree with his response: I’ll need more evidence for that charge, and corresponding evidence that large-scale nation-states or empires don’t “by nature” persecute minorities (Soviet Union, anyone?), before I get my lazy bum off the porch. To say the least, it’s peculiar to insinuate that localism was somehow the animating spirit behind the anti-Semitism that led to the Holocaust. By that argument, fierce militaristic expansionist nationalism would have to be seen as a form of localism. True, it may have fed off of some localist anxieties in the midst of rising nationalism and imperialism, but that’s a very different argument – an argument that may end up bolstering the case for localism more than undermining it. We need a suppler, more tentative, and nuanced discussion than a heavy-handed slap charging localists with inherent racism.

That’s the conversation-stopping aspect of the argument, and I was sorry to see Jody make it. However, another of Jody’s points actually invites more discussion. He points to the association made by some – including Chesterton – that Jews have been historically associated with a way of life, or even outright defense of, “rootless cosmopolitanism.” Here again there is a need for a good deal more nuance than such a statement allows, but this historical association is indeed a strong one (I have my doubts whether it can be said to be wholly accurate, since Jody also acknowledges that Jews have also been historically mistrusted because they form a distinct community within the context of the nation state. Such distinct communities are particularly subject to persecution, it seems to me, particularly in the context of nation-building when devotion to the nation is supposed to triumph over particular and localist loyalties. But, if so, this is an argument for a higher degree of local self-sufficiency, not for purportedly greater degrees of equality and justice ensured at the national level).

Still, if indeed there is something to the historical association that links Jews to justifications of “rootless cosmopolitanism,” does this make arguments against rootless cosmopolitanism illegitimate, even anti-Semitic? If there is a legitimate argument to be had against “rootless cosmopolitanism,” then shouldn’t it be made? Of course it should be. To say otherwise would be simply to say that any argument made by a once-persecuted minority cannot be engaged at the risk of the taint of racism. I find that charge absurd, though it does filter into much of the American inability to discuss issues of race. Frankly, it is the promiscuous invocation of charges of racism and the like that has made especially the liberal legal regime so ruthlessly unstoppable. Sometimes those charges are legitimate. Often they are conversation stoppers that prevent subtler analysis. The charge makes it difficult to distinguish between them.

But, perhaps finally Jody is insinuating that the localist argument has been made as a pretext for anti-Semites to persecute Jews, blacks, gays, etc. If so, what is being advanced is not an argument for localism, but a dishonest and bad-faith misuse of an otherwise legitimate argument. If this is the case, those arguing for localism should have any such pretext as much in their sights as defenses of “rootless cosmopolitanism.” Those defending a robust form of local autonomy from centralizing powers and cultural homogenization and rootless mobility (with its attendant irresponsibility toward places and people, as our recent economic collapse and environmental crisis attest) need to be fiercely opposed toward any efforts to employ localist justifications for specious ends.

In any case, I don’t find Jody’s invocation of “the Jewish problem” to be sufficiently persuasive to shut down this conversation. If anything, once one begins to think about it, I think its general inaccuracy opens the conversation up considerably.

Patrick, your comments are exactly correct. I have personally and recently experienced the phenomenon that when “progressivits” engage in debate with “localists”, the conversation usually defaults to some direct or implied charge of “racism, anti-semitism, ect.” It is, I think, a mechanism that is employed when they sense they’re losing the debate, or when they become emotionally involved in defending vested interests, such as their jobs or careers. Progressivists interpret the localist’s argument as threatening, and philosophically it is.

But the debate itself, between “localists” and “progressivists”, is actually a conversation between statists and anti-statists, though there are variations on that theme.

Patrick,

I may not be able to fully articulate this here, but it seems to me that localism is, by its nature, better at protecting minorities in the area than is the nation-state. Having a preference for “one’s own” is not just a localist tendency, but is a universal and beautiful one. The nation-stater has it; witness the outpouring of love for America and American exceptionalism over the next few days. The difference is that the localist’s love is grounded in reality, in a particular thing, while the nation-stater’s is grounded in ideology. A love for reality tends to open us to seeing good in the rest of reality; genuinely seeing a human face of another and loving it should make us more, not less, open to the humanity of the rest of those around us. Conversely, love of an ideology (in this case, patriotic ideology) creates no such effect in us. Instead, it closes us off to recognizing the humanity in the other precisely because that other does not fit into the ideological picture we’ve constructed and decided is true. Rather than discovering something in the person who doesn’t fit into the ideology, the nation-stater is left to impose his ideology onto that person in the hopes of making that person fit.

There was a fantastic article recently about how the modern military is sui generis in all of history because its members have no real attachments; they tend to be unmarried and spend more time playing video games and looking at pornography than they do writing/calling/skyping home. The author was speculating that this might lead to a better military, since the members have no reasons to ever leave service. My thought was that this was actually a recipe for war crimes, as people with no attachments to other humans are far less likely to see the humanity of those they capture or fight. Local attachments are important because they enable us to get outside the shell; we can only love in the particulars. Otherwise it always descends into ideology.

Excellent, thanks for pointing out that the greatest tragedies to befall the Jewish people came from centralizing structures like National Socialism. Let’s also not forget that they suffered substantially under the most rootless of all rootless cosmopolitanisms, Soviet Russia.

Also, the Jewish people, particularly many strands of orthodox Judaism, offer an excellent example of a people who adhere to place. With their strict observance of the Sabbath, they live close to their places of worship so that they can walk. These folks are well rooted in their communities, both religiously and politically.

Further, I think the invectives flowing from the FT crowd is rooted in a superficial and politically correct view of history. If you’re localist, you’re racist fails to take into account a number of racist political actions that have come from our own federal government, like the Fugitive Slave Act, the “imbecil” decision of Oliver Wendel Holmes, as well as just about every minor war we’ve engaged in, the Mexican War, the Spanish American War, and the occupation of the Philippines.

While localists have, and will continue to, commit injustices, so too have centralizers. One approach keeps error localized, the other universalizes error, bringing equal opportunity misery.

In my list of minor wars above, I did not list our injustices committed against Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, the Middle East at large. Many localists, libertarians, paleocons, crunchy cons, et al, have been against the federal policies in the middle east. Though it is a non sequitur, many times, advocates of these wars believe that opposition to them is equivalent to, or rising to the level of anti-Semitism. Similarly, appeals to localism, away from internationalism, implies some sort of disengagement from foreign aide, which substantially includes financial support from Israel. It is at this point, that support for localism becomes “anti-Semetic” and therefore a show stopper, even though it does not logically follow.

I think this might be where Evangelicals like Joe Carter are coming from. And it is at this point where debate will be squashed by ad hominem.

Casey: I think this might be where Evangelicals like Joe Carter are coming from. And it is at this point where debate will be squashed by ad hominem.

Well, no, that wasn’t my point at all. I see where you’re going but you veered off into internationalism when I was wanting to talk about localism. In fact, I’m struck by the odd turn that this discussion has taken to a sort of mix between a red herring and a tu quoque (“While localists have, and will continue to, commit injustices, so too have centralizers.”)

First, its a red herring because we are all localizers here. Bottum is from North Dakota, I’m from Texas, etc. We’re in favor of localism. You’re in favor of localism. I think everyone in this discussion is in favor of localism. The debate is not about which is better, localism or centralism (is that the only choices?) but about how do we encourage localism while not glossing over the more unsavory aspects that tend to come along with it.

Second, the focus on anti-Semitism at the national level is the true show-stopper. Patrick, for example, jumps from the idea that “minorities are persecuted at the local level” to “localism was somehow the animating spirit behind the anti-Semitism that led to the Holocaust.” Whoa. That goes from zero to nuclear in 15 words.

Ironically, it was also the point that Bottum originally made when he pointed out that its easy to gloss over the anti-Semitism (and racism, etc.) that tends to flow from localist attachments. It’s no doubt true that the greatest crimes against minorities tend to occur at higher levels of organization (i.e., the Jim Crow South, Nazi Germany). But why does that let us off from having to deal with the issue at the local level?

Patrick’s title for this post begs for an examination of Marx’s original approach in On the Jewish Question. While much of his analysis goes in directions which are not helpful to this discussion, parts of it are: particularly his understanding that the political (dare I say “cosmopolitan”?) emancipation which the Jews of 19th-century Germany were seeking, the ability to be treated equally in civic matters, is likely to be exactly the wrong kind of emancipation for them, an emancipation that may contribute to the creation of a state that will not provide the protects the Jews as Jews need, but rather will demand further and further assimilation by them.

Joe,

I apologize if I left that impression – you’re quite right that would be the conclusion to draw (MAD or something like that). What I wanted to emphasize is that these are highly complex issues, in some ways better left to the fine comb of historians than the blanket statements of philosopher types. One ambition in this post was to push back against the all-too common dismissive accusation that locality=persecution. I won’t deny that persecution takes place in localities in some instances, but argue that it does not in others – just as some nation states are better at protecting minorities than others. My simple point is that there is not a necessary connection between scale and persecution, but it’s difficult to make that point when someone starts lobbing around the accusation of racism.

I dare say that our susceptibility to thinking that there is a necessary correlation between locality and racism is a consequence of a certain view of American history. And, if anything, various defenders of localism before, during and after the Civil War severely damaged the case for localism by linking their arguments to slavery and Jim Crow (and it’s a connection that has well served centralizers ever since). But that’s different than suggesting that there is a necessary connection. I believe FPR is a place where the argument can be made in defense of locality that helps the work of disassociating the two.

As for the fine comb approach that helps us get beyond the simplifying language of “localism”: I think Caleb has hit it on the head in his post today – so I’ll simply direct you there, where I’m sure you’ve already been, but others should certainly go.

Anyone who would be so dim as to accuse the Jews of “rootless cosmopolitanism” has either never sat in on a truly beautiful Passover Seder nor helped throw shovels of earth to bury a jewish loved one.

Jews are uber localists throughout the diaspora as are Mormons and all people of Faith. When you seek the divine that is within, you tend to have a certain proclivity toward the essential building block of the local, your very own arse.

Perhaps it is a chicken and egg dilemma…it aint the prejudice against religions or races that is at work…it is the prejudice against the local…the non-National. The Jewish Question is the stalking horse to cover the more basic antipathy against anything questioning the glory of leviathan.

“Ironically, it was also the point that Bottum originally made when he pointed out that its easy to gloss over the anti-Semitism (and racism, etc.) that tends to flow from localist attachments.”

OK.

Bottum:

“So what is this problem at the root of localism? Part of it involves the simple philosophical point that all definitions—even self-definitions—require, at some point, an assertion of what the defined thing is not. There is no such thing as an entirely positive definition.”

What is pure sophistry is the implied suggestion that this “problem” at the root of localism is unique to localism.

Replace “localism” with “America”, “Western civilization”, or “the family” — or, for that matter, “Christianity”.

To the extent that Bottum is saying anything at all, he is pointing out that there are moral risks inherent to possessing an identity.

Brother Sabin, you are, indeed, waxing eloquent today!

Since Brother Sabin is being lauded here, I thought I’d point out that he has just posted his 300th comment on the site – a significant landmark, I’d think, with not a single misfire that I can recall. Following in second place – by a substantial margin, but still magnificent numbers – is none other than our military chronicler, Mr. Cheeks, with just past 150 comments. Heroic work, gentlemen!

Once again, nice insights, Patrick. They are dead on. And the comments also. Why, then, should I throw in my two cents? Well . . . Here’s just a few additional nuggets . . .

Does anyone believe that the racial problems in the American South either began with or could be largely defined by local attachments? Surely the localist advocates of the South (e.g. the Agrarians in I’ll Take My Stand) not infrequently defended segregation because it was the status quo and they were fighting to get back to a status quo ante. But race slavery in our country was largely made possible by early forms of a global economy. According to Tocqueville, slavery prevented the South from developing a real society and culture, and the events of the Civil War testify to this. That is, one of the main reasons the Confederacy failed (we all recall from elementary school or Ken Burns or even current scholarship) was that it had developed as a giant factory farm ruled by a narrow high caste. As T.S. Eliot observed many times, it takes classes not castes to create a culture; classes are culturally homogenous and stratified within that culture, while castes are distinct cultures coexisting, wherein one rules over the other.

Had the South developed a complete culture and a complete society it probably would not have seceded, because it probably would have had to have booted race slavery in advance of developing such a culture. So much, in any case, Tocqueville argues.

For my own part, let me second the observation that a) traditional anti-Jewish hatred must be distinguished radically from modern anti-semitism; b) modern-antisemitism clearly has its roots in a kind of anxiety among those seeking to build modern nationalist movements that Jews had already what, say, pan-Slavs did not: an inherited sense of communal identity and loyalty to cultural tradition; and c) modern nationalist movements were not created to stop everyone from falling in love with foreigners and becoming world citizens (though, if that’s your view of Communism, then actually nationalist movements did form against such things), but to break down traditional local attachments and subordinate them to a defined national consciousness generally headquartered in deracinated urban centers. The rooted locals and rooted cosmopolitans both lost out to the rootless nationalists.

If anyone can show me one instance of a truly localist ethos that actually results in some kind of categorical injustice (racism, antisemitism, etc.), I’d be most grateful, as I would also be most surprised. That kind of injustice is to be distinguished from the simple privileging of family and friendship obligations over those of hospitality to the stranger.

To just tag a bit onto James: Hospitality to the stranger, in my experience, is typically more to be expected where there is a more secure sense of community.

And, my palsy writes,”The Jewish Question is the stalking horse to cover the more basic antipathy against anything questioning the glory of leviathan,” where “leviathan” is empowered by what?

Taxation….of course!

Where taxation in our country, state, and locale inevitably devolves to confiscatory taxation strenthening and empowering and corrupting the apparatchik, the politican, the party hack. And, how is that accomplished?

Well, one very successful method is the ever reliable redistriubtion scheme(s).

Which is why the founders abhorred these redistribution schemes and rejected them out of hand because they knew that all efforts to redistribute the wealth, to make it “fair,” would pervert and derail the republican process and threaten liberty.

300 eh, …this sounds like a malady . Such are the pathologies of the “dispossessed” who assert….after a lengthy career in larger businesses that they like “to work alone”. A client forces email on a body so they can talk to him from Japan while he sleeps and then a monster is born when them tubes of “the internets” is discovered and said monster stumbles on this site. I’m a victim here.

Cheeks, your malignancy aint as advanced, you still have time

Comments are closed.