It is autumn in Amsterdam and damp. The twilight is coming. I await a streetcar to take me home through the labored-over canals, the old working-class neighborhoods on the Amstel. They bear the marks of the generations’ industry, of their interest in their hard-won place just below sea level.

At the streetcar stop bicycles are strewn about, empty French fry boxes, newspapers and napkins are glued to the ground by rain, and perhaps twenty people try to remain dry with me under the tiny metal awning. A black umbrella lies on the tracks, no doubt dropped earlier in the day, after the wind turned it inside out. It looks like a crushed bug. The Dutch treat umbrellas and bicycles as Americans treat paper plates. It is not uncommon to see a few broken on sidewalks—especially after windy rain.

The tram (which the Dutch pronounce “trrem”) arrives but waits a few feet from the stop with its doors closed. It cannot proceed to the landing until someone picks up the dead umbrella. No one does. Everyone wants to get on the tram, but no one moves the umbrella. One thing the tram driver and her future passengers share is the belief that someone else should do it: non serviam. And so I pick it up and place it in a trash can. The tram proceeds, takes on its load, and bears us off to homes or heated restaurant terraces or night work. No words are exchanged between the passengers.

A little more than a year ago, an election season ended. Depending when you began counting, it covered six to eight seasons of nature. In the months leading up to the election, Continentals called it merely “The Election”—having no need to qualify it as “American” or “presidential”. Most Americans think the whole process took place within the United States. They have heard precious little about what transpired outside of the U.S. during the election season—particularly in Europe.

Although Europeans’ general prejudice is widely known (pro Obama), their vicarious participation in the election process is less well known. When change was needed, they became part of the “We” in “Yes, We Can!” It was their duty to do whatever possible—even just talking up the junior senator to their peers (but in some cases traveling to America to campaign for him)—in order to make this necessary change. It was their job, no one else’s, to make it happen. Alas, there were tears when he won. Others put hand to heart. They were jubilant. For many it was a personal success, as if they had had a kid or gotten a promotion. It marked the end of many travails—eight long years of angst, grating their teeth about what that nefarious Bush-Cheney dyad was scheming up this week. Now the leaden hate they had had for Bush was transformed—ka-bam!—into love of the man with the golden name. And the road to Progress was once again being paved with good intentions.

This stark example is illustrative of what is generally true: a great deal of everyday Europeans have become convinced that what happens in America, and America’s interests abroad, greatly impacts their personal lives, rather than merely their national interests or bottom lines. As a result, these housewives, software engineers, bakers, janitors, brooding adolescents, cab drivers, businessmen, and shippers have become deeply concerned about what happens in unpronounceable Iraqi towns to individuals whose names they do not know; in American prisons the inhabitants of which they would not care to meet; and to untold millions of American statistics who do not have health insurance.

These Europeans distract themselves with the illusion that the solutions to the world’s biggest problems lay in what America alone does. This belief is founded on the assumption that America is the cause of these problems—forgetting that some of the problems have their provenance from when the Dutch, Ottomans, or British were at the helm. The logic explains domestic problems as well: something over there is responsible for a problem here. For example, a popular attitude to this generation’s Jewish Question: Israel and the Palestinians. If only peace in Palestine came, if only America divested Israel, then our Muslim citizens would integrate joyfully into our European cultures. Ergo, the Norwegian Nobel committee hitched the president to the cart that will be driven by Europeans to solve the problem that is America—thereby solving the world’s problems. Both the roots of, and solutions to, domestic social and political problems are externalized.

I write about their interest in America; however, it is not limited to America. Political elites in Western Europe take the domestic concerns of other countries—China’s relation to Tibet, seal hunting in Canada, AIDS in Africa—and make them existential concerns for themselves and their nations. They colonize the concerns of others. Then ordinary people begin to think that these foreign concerns matter for their own personal happiness, distracting themselves from the hordes of problems at home. In the last few decades Western Europeans have built a tradition of vicarious participation in the problems of others, supposedly less fortunate.

The paternalism of this new age colonialism is in some ways more brassy than that of traditional colonizing in which you would have actual colonies. At least when Europeans had colonies they had knowledge about them, and would travel to them, invest in them, live among the natives—even romanticize them in song and verse. They were concerned with their actual interests. None of this is necessary if your colony is an idea in a head instead of a place on earth.

Perhaps the reader is finding none of this strange. She may be thinking “obviously a modern, educated person would be concerned with the state of the world, and its diverse peoples.” The peculiarity of such colonization is perhaps only made manifest when you think of other cultures and countries of the world—popularly called “the Third World”—colonizing our concerns. Imagine large swathes of Mongolians or Malaysians vicariously participating in problems the French auto worker unions, English bovine diseases, the trafficking of girls from Eastern Europe to Amsterdam’s brothels, the fornication of Italy’s premier. Imagine them spending there evenings and weekends brooding over these various and sundry concerns.

Notwithstanding, what makes the colonization of concern so attractive to Europeans is that it is so suited to our age. Our tizzied voyeurism is fed by installing news cameras all over the world to monitor the colonies, and we are fed with up-to-the-minute reports via the “information super-highway”. This absentee colonialism allows one to ‘profit’ without getting one’s hands dirty. And it allows guilt-free escapism. It is also suited to our age because it is completely voluntaristic, as well as being duty-free. Since taking interest in the problems of others costs little to nothing in terms of blood and treasure, it is readily done. Collectively, it falls under the name of foreign aid. While this can be expensive, nations don’t actually suffer for it, not like the British did for the Allies’ cause during WWII.

Colonizing concerns also costs nothing in the nominalistic culture of freedom of speech and expression, in which words are not all that meaningful (no matter what your professor told you, nominalism is really why freedom of speech is uncontroversial in the modern age). So, why not take a position on everything, regardless of what you know about Iran, the oil industry, fisheries in the Indian Ocean, Greenland’s glaciers, the spread of AIDS in the Congo, or crop failure in Sri Lanka? If the position becomes manifestly untenable (or too unpopular), then take the opposite position. If you really care, you will be concerned—and especially concerned about the concerns of others. Alas, what began as a polite tradition amongst nineteenth century newspaper readers to be informed has by now metastasized into an Empire of Empathy. More and more corners of the world are being embraced by a soft Euro-hug.

The irony of it all is that Europeans have become focused on exactly the things that they cannot change: international and universal problems, as well as domestic policies of many a foreign nation. What they could alter at home, through concentrated, personal effort, is delegated to a committee or desk to deal with. This luxury of concern—the ability to define one’s personal interest in a far-away entity or place—allows ordinary people to believe that they are not wasting their lives away by concerning themselves with international politics, that they are not neglecting their duties when they arbitrarily choose which foreign land’s domestic politics to tie up with their personalities. What is on the doorstep can be ignored, and is—all except the newspaper and the tweets of certain birds.

In this, we have seen a virtue corrupted. Concern is a form of care. The essence of concern is looking out for the good of the other: love of neighbor. Although etymologically distant, the Middle English-derived “care” and the Latin caritas share something in connotation: the active attention of one for the other implied by “I love you” and “I care for you”. Personal acquaintance, meaning personal knowledge, is implied and necessary. The scandal of the particular is present in both love and care: they are neither general nor abstract. Nevertheless, we now mostly care for things that we do not know. We love without knowledge. But love without knowledge tends to be violent—an act of the will minus intellect. You care so much that you want to change things, to set them right. Yet you have no idea of the effects of your proposed changes (or sometimes even what should be changed). Throughout the West, the virtue is corrupted by ignorance.

In Europe, concern is further corrupted by a disease of the soul. In order truly to love your neighbor as yourself, you must first love yourself. If you hate yourself and feel guilty about your past, then how can you truly love the other? Europeans hate themselves in this way—not individually, but they hate the bourgeois Westerners that they have been (and still basically are). They cling to hope and change in large part because of this. All the more, the childlessness of Europe is as much a result of self-hate as self-love: they do not want to re-produce their selves. Guilt about colonialism, the Crusades, Western imperialism, environmental degradation, is coupled with a need for recompense. The psychology it produces is anti-self—and against love of self—in general. It functions like what may be called the vegan logic: since I cannot enjoy meat, no one should. Since I cannot enjoy life (because of ancestral guilt), others should not be able to either. The conclusion: I cannot make myself right; therefore, I must make the world right. In this, Europeans are in danger of losing the foundation of brotherly love, and a culture of genuine concern.

Should Europeans stop colonizing concern they would have a lot of free time to fix their own problems—the umbrellas stopping the streetcars. This would only become possible were their goals more modest than universal peace and harmony, and if they put a moratorium on pointing out the specks in their neighbors’ eyes. Nevertheless, even when Europeans do focus on problems closer to home, there is domestic colonization of concern. Social democrats and labor parties have even colonized the concerns of minority groups in Europe. The result is that white, Western elites sit around talking almost exclusively with white, Western elites about how to integrate Muslims. (Imagine if the NAACP was run by a cadre of condescending, white progressives.) Alas, there is no end in sight. Just the other day, Norway colonized the American presidency.

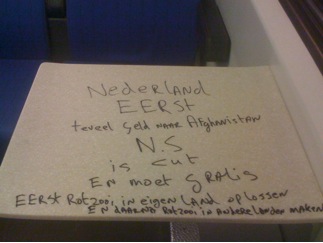

Dutch patriotic graffiti on a train “Put The Netherlands First! Too much money [is going] to Afghanistan. The national train service is cut and must be free. First fix the junk in our own land. After that [fix] the junk in other lands” (Autumn 2009).

As the philosopher Peter Lawler is fond to say, conservatives are in the habit of throwing nihilism around like a Frisbee. They decry the nihilism of Europe. They (rightly) lament the learned “dying togetherness” of the European café culture. Conservatives also point to Euro-decadence in terms of sexuality, work, entertainment, and entitlement. Yet being able to choose your own concerns is in fact much, much more decadent. And as we have seen, it has become the European way. Nevertheless, it is also the American way. Well, it is an American way. Since the Second World War, Europeans have become more American, and not in the right way. They are now more than ever rootless individualists, being bound neither to family, tradition, country, nor creed. They are motivated by rights (entitlements) and consumption: “collectivist consumers”, in the Danish writer David Gress’s coinage. They can define themselves as they please, and re-define at will.

However, few are very creative in their definitions. So they define themselves based on what is fashionable: International activism is the zeitgeist; colonizing concerns the modus operandi. The man from nowhere thinks that since he is bound to no one place, he is able to be everywhere or anywhere he wishes. Nihilism is not only about nothingness but also about nowhere-ness.

It would be wise for Americans, and especially American conservatives, to know what is going on in Europe. It may improve their understanding of their own land. American coastal liberals are basically carbon-copies of the European social liberals, and—all the more—America has always flirted with frontier-style, ideas-driven politics (in which colonization of concern flourishes). It is charged, and often true, that America constantly tries to escape from the scandal of history through historical amnesia, preferring to march for pure ideas like “freedom” than hold fast to reasonable, if blemished, political and social traditions. However, recent interruptions in America’s dominion—both at home and abroad, fiscal and military—mean that she must come to terms with history as a problem without a (perfect) solution. This comes at just the time when Europeans are trying to shirk the problem of history by forgetting and busybodying.

Jonathan D. Price is a writer living and working in Amsterdam. A frequent contributor to Dutch and European media, he is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Clarion Review (www.clarionreview.com)

I thank you for this thoughtful essay. You express a number of interesting notions. I would suggest there may be alternatives or at least additions to some of what you say. First, I wonder if America is to some extent like Rome – no matter where you lived in the Roman Empire – you aspired to be like a Roman, you concerned yourself with Roman politics. Rightly so since Rome ruled the known world and was likely to have an effect on your life if in no other way than shipping your sons off to some Roman military campaign. In the sense that the US is the superpower what we do has a huge effect on those Europeans. Their sons are likely to get sent off to military campaigns we initiate. Their concern with our politics is understandable. Their concern re: Bush was not just escapism. Their concern was rooted in legitimate distaste for a war they saw as against their interests and in some coutnries, a war which took their sons and daughters.

Second, I spent some time in Denmark last summer and was inclined to think for a nation suffering from disease of the soul they acted more like Christians than us allegedly God fearing Americans do. They were uniformly polite and welcoming. They are very focused on their children – even if they have only one. They are very family oriented and for sure much less into stuff than we are. They have less crime and seem to have a passion for honest government. And while they may live in a city, they return to the family farm with their children often and value their traditions. More important – they work to preserve those traditions.

Third, I think the “guilt” thing is often a function of some segment of the population – urban, affluent and well educated. But there is a pushback against this attitude among other folks – the further away from London one gets – the less people feel guilty about empire and the more annoyed they are with those who do feel guilty.

Finally – I think to define “Europe” as some homogenous mass is inaccurate and misleading. There are clear differences among European nations. So while I absolutely agree we should pay attention to what they are up to, we should do so recognizing that what they are up to in the Netherlands is not quite the same as what they are up to in Italy etc. And we might also consider that sometimes what they are up to is rather interesting and productive.

This is just an excellent essay that gives account of the current European deculturation. A deculturation long triggered by reductionism and sundry ideological distortions spawned by the Enlightenment Project whose final result was a collapse of the order of western man and a noetic disturbance that acted to sever the “constitutive core” of man with the spiritual realm.

The most significant example of the Western cultural collapse is the inability to identify Islam as our greatest threat, and to deal with them accordingly.

Come on Cheeks, Islam is hardly the greatest threat we face. There just aint enough of em, in particular the murderous sector of em to constitute our top threat. That distinction goes to the mirror and the cheerfully clueless face staring back at us.

The Vicarious Global Agora eats sturm und drang by the fistful, it provides the sanguinary drama a human needs as he festers away within a circus of bureaucracy and its global service jobs. Descartes had it wrong…the real agenda of modernism is “I watch therefore I am.” . The Homunculus sits aboard a Barcalounger and he loves his telly remote.

Caricature is the new reality.

Oh yep the Europeans should stop colonizing their concern after their economies were nearly blown up by Wall Street!

After listening to some of the debate at COP 15, Europe’s “colonizing of concerns” is clearly visible. When the less developed county’s call for a world democracy to settle the matter, the patronizing nature of this concern becomes crystal clear.

Reminds me of Irving Babbitt.

ah, we can always count on Cheeks to explain the history of western culture and everything else to us morons in two pithy sentences so overpopulated with words and ideas that only the author (who is privy to the footnotes) could fully understand them. at least that way no one can assail his inscrutable mind. thank you God for giving Bob Cheeks the wisdom of the prophets.

as per the article. some pretty dubious generalizations there. especially the bit about europeans hating themselves. written as if it were verifiable fact. the truth! there were some good observations… but in general? it just sounds like the usual trashing of european liberals by some sanctimonious american living in their midst.

this website deserves better.

eutychus, it is, of course, a pleasure…to either educate or annoy you.

neither, of course. but you do amuse (and frighten) me a great deal.

Well, in that case, it’s all good. A little emotion is uplifting. As for you, I look forward to your wit, critiques, and sarcasm…though, as you know, you are among professionals here.

yes, yes. but professionals occasionally need to allow the uneducated village idiot onto the porch now and again. that way when the emperor passes by…

Exactly!

[…] in the Netherlands, originally appeared in the Dutch daily newspaper Trouw (January 2, 2010). The Front Porch Republic article that Kennedy references is also soon to appear in the well-known Polish conservative magazine […]

Comments are closed.