Rock Island, IL

Obviously there is a fortune out there waiting to be made by someone who can take well-known poems and re-write them for discriminating readers. Poets are already living high off the hog; I see no reason that parodists shouldn’t also.

My own attempt, The World’s Best-Loved Poems Improved Upon, soon to be published by Rolling & Doe, should give poetry lovers hours of delight and quality reading. It should also allow me to quit my night job as troll-slayer at FPR and move into the Projects in northwest Rock Island.

(I considered rewriting America’s favorite Christmas carols, but the thought of seeing my book reviewed by a certain formidable and learned Doctor of Divinity dissuaded me. I am a man of very thin skin.)

The idea for this book came about one day when I was reluctantly doing a unit on the Beats in my American Lit class. I realized that I could make shorter work of the misery by rewriting certain major poems of the Beat movement. I don’t want to give away too much of my work—there are copyright issues at stake, after all—but a good example is this slight variation on Ginsberg’s masterpiece, “Howl,” which variation, I think most readers will agree, demonstrates that simplicity and subtlety do often go together:

I saw the best minds of my generation

Ah, forget it.

That Coleridge was an opium addict is well-known. It did not seem impertinent to me, therefore, to take one of his odes and recast it. I won’t reproduce the poem here, but the title, “This Lime-Wedge Drink My Prison,” will suggest, I think, the general drift of my alterations. It is based, loosely, on the life and habits of a denizen of Elba, New York, who is inordinately devoted to libertarianism, secession, Genny Cream Ale, the Muckdogs, a fictional girl named Wanda, and the memory of John Gardner.

But I would not have the reader think that this book is all about ne’er-do-well chrome-domers. Much gravitas may be found herein. It pays fitting tribute, for example, to several American greats in such paeans as “Because I Could Not Stop for Condoms,” “Pat Her, Son!” and “Thong of Mythelf.”

Now it is generally agreed that some of Wordsworth’s poems are too long, so there’s one in this collection called “We Are Five” and another called “Expostulation.” A third, titled “Intimations of Immorality,” reiterates the fact that the “rainbow comes and goes” and ends with “thoughts that do often lie too deep for queers.” As the original was (to use Emerson’s phrase) the high-water mark of the nineteenth century, so this may well be (for so a man may hope) the high-water mark of the twenty-first century. That exacting critic, Time, now also a major magazine, will tell.

And speaking of poems that are too long, the same goes for Milton. Of the Paradise Lost, said Dr. Johnson, “none wished it longer,” so I’ve scaled it back to a couplet that preserves not only the blind bard’s original intent but also his favored diction and syntax.

Of man’s disobedience and all our woe

Sing, Heav’nly Muse, with warbling notes and slow.

(In the original poem much happens between “Of man’s first disobedience” and “They . . . with wondering steps and slow . . . took their solitary way,” but to tell you the truth most of it is filler, and all the other published poets I’ve shown this to have told me they approve of my abridgment—nay, think it an improvement.)

I expect to make a good deal of money off of Robert Frost. Again, my lawyers suggest I work by partial revelation here, but let me just say that the rewrite of “Stopping By Woods”—in no way autobiographical—has a stanza I’m particularly proud of:

These girls are lovely, dark, and deep,

And I’ve no promises to keep,

Nor tests to grade before I sleep,

Nor sleep to sleep before I weep.

I should say there’s a subtlety of expression here that I do not expect all readers to catch. And, to tell you the truth, my editor and publisher were both worried about this. But as a profound poet trying to make a comfortable living I can’t really trouble myself about that fit audience though few. My loyalties must be to my art, not to any people who may or may not read it. Were I to start thinking about poetry in the social context, I’d be sliding down that slippery slope toward place, limits, and liberty. And then what? Localism? God help us!

Nor let those impatient with Keats think they have not been done a great favor here:

No, no, go not to Lethe. Neither watch

ESPN, tight scripted. But glut thy

Ennui on “Oprah” and “The Morning Show.”

Or:

When I have fears that I may cease to be

I let Fanny Brawne have her way with me.

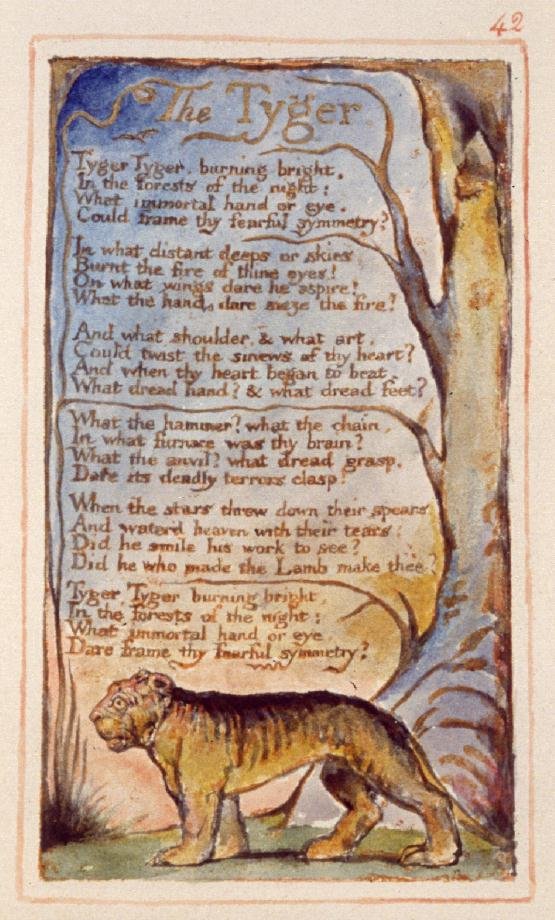

The savings in time alone is worth the price of this beautiful volume ($69.99), handsomely illustrated with several etchings by William Blake, many of them published here for the first time, including “Rousseau You Knave & Fool” and “Mrs. Blake Is A First-Order Nag.”

And speaking of Blake: those who order now get a special CD featuring a certain Swede reading a variation of Blake’s “The Tyger.”

Tiger! Tiger! burning bright

In the brothels of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could tame thy fierce adultery?

In what distant lounge or bar

Didst thou manage to break par?

On what bedsprings dare aspire?

What the maid who doused thy fire?

And what buttocks and what gam

Put thy Caddy on the lam?

And when thou drov’st into the hedge,

Whose dread swing? With what sand wedge?

Who’s the waitress? What’s her name?

In whose panties is thy brain?

What the backseat? What dread grasp

Dare her pink brassiere unclasp?

When the fans threw down their cheers

And water’d fairways with their beers,

Did she smile her work to see?

Did she who bedded hoardes bed thee?

Tiger! Tiger! burning bright

In the left rough or the right,

What all-roving hand or eye

Dare tame thy fierce adultery?

© Bar Jester 2010

Who’s the waitress? What’s her name?

In whose panties is thy brain?

What the backseat? What dread grasp

Dare her pink brassiere unclasp?

A youthful harlot’s curse?

“Thin Skin”? You? Surely you jest.

We can only hope that there is some Robert Burns redux, produced about the time the liquid amber reaches the bottom of those letters “L” to “G”.

Sabin,

You should have seen Peters cry like a baby at the conference at Notre Dame when he was asked a question that was just too hawd fow the wittwe pwofessow.

BRAVO!

Too good. The question this piece brushes against is certainly becoming one of the more interesting debates of our time. A recent article over at The Chronicle for Higher Education criticizing Emerson set off a storm of response.

http://chronicle.com/article/Giving-Emerson-the-Boot/63512/

I side with #12 and especially #17 in the comments that follow the article.

P.S. The Tiger poem was outstanding. Blake is applauding from beyond the grave.

It’s little known, but in fact scientists have indentifed the “doggerel” gene.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/MAR05/poeticpathology/genes/heckleandfrye.html

First, you mock the ways in which most Americans celebrate Christmas, and now you assault that even more sacred American tradition, the recitation of poetry before the hearth with one’s friends and family. I’m not sure how you will survive this stab at such a universally commended and sacrosanct ritual. From Orono, ME to Palo Alto, patriotic Americans will likely burn you in effigy for tinkering with and trivializing the one activity that still unites Americans after our two centuries of dispersion and “diversification”: those enchanting evenings of poetic declamations.

Know that I would accounted be

A member of that company

That comes with torch to Peters’ house

To burn his porch and tip his cows,

To break his banjo, bust his fife,

And have a diddle with his wife.

is this the alternative occupation you mentioned in your previous essay? I fear for your family if it is!

I wish now that I had only read your version of Howl.

Comments are closed.