Henry County, Kentucky. If the young artists I know have any overmastering desire, besides becoming famous, it is to be original. And by that they typically mean creating something new and different, doing something not done before.

I don’t wish to overstate the matter, as there is a lot of art from the last hundred years to love. But in general, given the mood of our age and also several thousand years’ worth of artistic predecessors (who have already discovered everything from the Archaic smile to the Petrarchan sonnet), something new-and-different these days often means something atraditional, violent, irreverent, shocking, ironic and/or ridiculous. This is a trend with a long arc, and so it was that the century just past was the century of Dadaism, Surrealism, Existentialism, Nihilism, prepared piano for wholly unprepared audiences, and naked performance art.

Wendell Berry, who has proposed an alternative way of thinking on so many matters, gives originality a different definition in his latest book, a collection of literary essays titled Imagination in Place (just out from Counterpoint). “Original” is a fairly old word with numerous meanings, but the meaning Mr. Berry takes to be the best is that quality of a writer who has plumbed his origins, meaning especially the place he lives and the people of that place. If the writer is a good one, he may come to know, understand, and finally imagine his own place so well that he speaks for his place and knows what needs to be said about it.

If you are a religious person, you could say Mr. Berry is talking about a writer’s call to witness. If you are a nonreligious but ethically-minded reader, you might say he wants a writer to do justice to his native ground. (Or hers; plenty of his appreciative essays are about women.)

Ego underlies any creative act, as it must, since any artist is the filter and the voice for what he is driven to say. But there is humility as well as rootedness in the kind of originality Mr. Berry loves, a humility that will not be found in the work of those who use their past, their current city, or their color-gathering trips abroad as veins of ore to be mined in order to further a career or to enable themselves to “find their own voice” (a phrase Mr. Berry clearly dislikes). Art, for him, is an attempt at wholeness of expression that must come from a desire for wholeness and haleness in the life the artist is living, and cannot be separated from it. In some way—through imagination and (for the fortunate) inspiration–a writer becomes a medium for his own piece of ground and the people who are, like him, bound to it. Mr. Berry explicitly praises the work of Wallace Stegner and James Still for just this lack of separation. And it can’t be happenstance that most of the writers Mr. Berry celebrates here have been in some way conservationists.

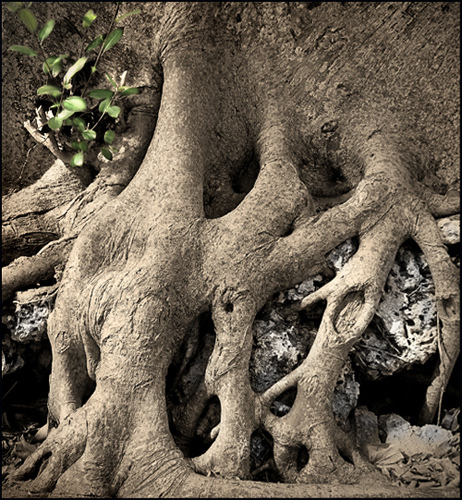

Occupied as he always is with precise language, Mr. Berry argues that there can be no national imagination; a national or international language is an Esperanto of vagueness and cliche. It is only our own town or neighborhood that is specific enough, and someday knowable enough, to enable a capable writer’s imagination to imagine it clear and whole. Imagination is the organizing force for originality, and imagination starts not in the mind, but in the world our mind inhabits and comes knowingly to love. In other words, it starts in a place, with its bare toes in our own muddy mother earth.

If what we see and experience, in our country [i.e. our local place], does not become real in imagination, then it can never become real to us, and we are forever divided from it. And for [William Carlos] Williams, and for Blake, imagination is a particularizing and a local force, native to the ground underfoot. If that ground is not in a great cultural center, but only in a New Jersey suburb, so be it.

For those writers who do not live in their natal place, he offers comfort in the example of the poet Jane Kenyon. Ms. Kenyon was a Michigander who married the poet Donald Hall and then moved with him to his family’s farm in New Hampshire, a place that was home to him but foreign to her. There, like Ruth, she “understood her exile as resettlement,” Mr. Berry writes, and spent the rest of her life culturally homesteading in both fear and hope.

“Maybe/ I don’t belong here,” she wrote once. “Nothing tells me that I don’t.”

As horrifying as it might seem, the movie Orange County actually captures this idea quite well, even to the point of being preachy.

This reminds me of the residents of Illiers changing the name to Illiers-Combray because they felt Proust’s fictionalized version was so accurate.

I sometimes have an original idea, by which I mean a bad idea. If an idea is mine alone, it is a worthless idea; if it is an idea that has real history behind it, it has a better chance of being true. I think it quite unlikely that God would withhold the truth from generations of saints to reveal it to one sinner in a Texas suburb. When I get an idea, what I look for is not originality, but connectedness. “This is interesting,” I say to myself, “is there any parallel in Aristotle or Augustine?”

True originality consists not in discovering new truths, but in applying old truths to new situations.

The difficulty in creating art of and about a particular place, is that so many places today seem wholly indistinct from one another. That’s a real experience; an alienation that can’t be wished away by attaching ones self to a place ( where, again? The on-ramp? The TGIF?).

John – I think the truest sentence in that entry is the last one. Just as Scripture unfolds itself in new ways with every generation (but, of course, never actually changes) the truths of… well, human existence… take on new meanings from age to age as well as from person to person.

The truth (and the good, for that matter) never changes – kudos for mentioning that – but is in no way a barrier to originality. Berry’s concept of original thought is, for the ‘original’ thinker, the blossom which proceeds from (and can only proceed from) the seed of truth – in the soil in which it spreads its roots. Does this make sense?

And Uland, I agree with you wholeheartedly. I’m from rural Nebraska and right now I’m living in the suburbs of Northern Virginia. The sterility and ‘sameness’ of this place drives me crazy.

This tendency to be original as it is commonly understood finds much of its origin (pun intended) in the poetics of Ezra Pound. Pound’s famous slogan among the Modernists of his day was “Make it new.” I think Eliot’s Waste Land is a greater cultural and poetic achievement then Pound’s Cantos – particularly with the infectious fascism throughout. Pound was consistent with his beliefs, and his fascism was an outgrowth of his Modernism. Eliot lamented the loss of the traditional during that era of progress – Pound embraced it and sought to build a culture out of it.

But it was Pound, and not Eliot, who ultimately influenced the poetics of Zukofsky, Reznikoff, and Oppen, and later Olson, Creeley, Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, Levertov, and the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets. Some of the names after Ginsberg sound unfamiliar? Precisely. Poetry following that strain came to mixed results, and is part of the reason that poetry isn’t taken seriously today.

Reviving the soul of poetry requires a return to the poetics of Eliot. He carried the torch. He expressedApart from that, poetry will be nothing more than keeping up with Modernity’s Marxist Joneses.

While the man certainly had his flaws, Pound as bête noire is somewhat ironic given the context. It is true, though, that his work has influenced a great many poets — even up to this very day.

Have you read Real Presences by George Steiner? He makes a radical distinction between “originality” and “novelty.” That which is original comes forth from a source. That which is new for the sake of newness has no roots and no genuine criteria to judge its value: it is good simply because it is new and newness never lasts.

The arts are not interested in originality — I wish they were! — but with novelty: a radical break with origins and novelty for novelty’s sake. I believe this is exactly what you’re saying here with a more precise vocabulary.

—

But I wouldn’t say the schools you’ve mentioned were exclusively concerned with novelty. Hegel’s prediction of the death of art occurred with the actual death of philosophy (metaphysics) and has changed art and philosophy in ways Hegel couldn’t have predicted.

Artists have no reason to be concerned with mere representation of the world since a camera (technology) can outdo art (techne) when it comes to photo-realistic images. Dada, anti-art, and such movements are, more likely, an appropriate upheaval of certain dying modes of art. That is to say, they originated out of dying arts (or was the dying of art itself) and are themselves historical manifestations of our original process. The very fact that such “anti-art” movements (ironically) become art movements reveals that we are increasingly concerned with the ontological bearing of art: what does it mean, how is it used, and so forth. Perhaps Dada is a necessary step in revitalizing art?

I haven’t read Mr. Steiner’s book, but thank you for the suggestion.

I am not much of an aesthetic theorist. But I believe there is now both a strong desire to define originality as novelty, as Mr. Lundy says, along with a strong attraction for the ugly and the senseless, which goes hand in hand with these attempts to be always New. So much art feels like an adult version of little boys throwing rocks.

There are great works of art that are full of ugliness–the broken body of Christ in the Pieta, Oedipus Rex. But there is a beauty among the tragedy that reaches toward a wholeness and a moral logic that is not found in many (fortunately not all) modern works of art. All of the movements I cited are movements of despair, not tragedy; there is no sense to be made in them, often no standard to fall short of. (I would except a few Existentialists from that broad generalization.)

And often, as with the play Waiting for Godot. Dali’s paintings or Surrealist poetry, the work that comes out of these movements is set nowhere, depicts an unrecognizable landscape, or uses a language of less and not greater intelligibility.

Which reminds me that Mr. Berry’s new book also includes a wonderful essay on As You Like It and King Lear.

“So much art feels like an adult version of little boys throwing rocks “…or perhaps little girls playing tart-up…because so much of the modern world feels like a juvenile version of little boys throwing rocks or little girls tarting up.

Unintelligibility or base mockery in art is a manifestation of the rank confusion that attends a hyper-technological, Cartesian-Joned life of modernity where distance from life is the outcome.

Popular Culture, the most productive petri dish of our this Age of Malcontent is the chief venue of all this shock appeal. A major portion of the artist’s skill goes toward the skill with which they market their slaps in the face. Fortunately, the artistic spirit still burns and if one cares to look for it beyond the vicarious agora, you can find skill and love in artistic expression that is not so saturated in the cynicism and ennui of the age. However, one does have to enjoy the satire of a gazillion dollar balloon dog or diamond-encrusted skull because they are the graphic representation of Voltaire’s arch proclamation that the

” world will not be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest”. The new king and priesthood is of course, the same people buying the artistic equivalent of a tantrum. Freedom, it might appear, has its downside.

Not that I want to compliment you on your comments Lundy, you make too few of them…. but thanks for the reference to Steiner and if R. Mutts urinal is a required step in revitalizing art, it sure is taking a long time, this revitalization.

Looking forward to reading Mr. Berry’s new book. Related to these issues, I’d recommend Roger Scruton’s books “Culture Counts” and “Modern Culture.” He has a new book out, “Beauty,” which I’ve ordered but have not received yet, that looks very promising.

Comments are closed.