The second act – “Love and Marriage” – I thought was particularly striking, given the setting of the play in Grover’s Corners in a theater in Greenwich Village, New York City. Walking to the theater, I had to pass a number of sex shops, and found myself reflecting as well on the attraction that New York City holds to countless young people – especially recent college graduates – who are enticed especially by the opportunity to try out countless different partners in a dense population of prospective mates. The television program “Sex in the City” was essentially based on this aspect of New York (and, for that matter, countless 80s and 90s sitcoms, like “Seinfeld” and “Friends”), the promise of endless sexual partners where variety reigned, regret was unfashionable, and commitment, if present at all, a fuzzy possibility in the distant future.

In the second scene of “Our Town,” the main young characters – Emily Webb and George Gibbs – speak haltingly and charmingly of their growing affection and love, in terms almost unrecognizable not only in New York City, but one dare says in the world that we increasingly inhabit, one distant (if not merely in space and time) from Grover’s Corners. George struggles with his felt sense of obligation to attend college to study agriculture, wanting more to stay put, to marry Emily and to start work on his farm immediately. He states, “I guess new people aren’t any better than old ones. I’ll bet they almost never are.” He then tells Emily that there’s no point going away to college if you already know the person you are “fond of,” and that person is “fond of you.” While they both prove to be terrified of marriage on the day of their nuptials – each engaging in a “soliloquy” that we are to understand is an expression of their inner fears – like their parents, they learn to live together and grow in love, and when the time comes, to die alone yet mourned by their community and join the fellowship of the dead on the hillside above the town.

The juxtaposition of Grover’s Corner and New York captures the essence of two different worldviews. In the one, the challenge of human life is to reconcile our capacious longings with our need for home, belonging and fellowship, and the scales are tilted decisively in favor of the latter. Mrs. Gibbs speaks longingly in the first Act of her desire to visit Paris before her death, but we discover at the end of the play that she gives her “legacy” – which was to fund her journey – to her daughter and her new husband so that they can make some repairs on their farm. The play’s end shows us that our ultimate orientation toward Eternity throws into relief the insignificance of the affairs of daily life, yet that the modest daily acts of cooking, cleaning, discussing the day’s events, are suffused with a kind of beauty and significance that too easily escapes us when we fail to notice the fact of living. The fellowship of those with whom we pass our lives, and with whom we ultimately lay in burial, connects the diurnal to the eternal.

In the other worldview – there again all around me as I exited the play into the Village bar scene in full swing – institutionalizes discontent, reinforces restlessness, and fosters and endless and intense suspicion that something better lies around the corner, reducing any commitment we might have to the “given” in favor of the “not yet.” “Belonging” is understood to be complacency; limits are seen as unacceptable oppressions; imperfection is a condition needing cure, solution, repair – and barring those, escape. Both conditions generate regret, because we are creatures of belonging and longing. Still, in the decisive manner that we have institutionalized discontent we can see the source of today’s most pervasive pathologies – ranging from consumerism to indebtedness, from profligacy to the nature’s plunder, from divorce to the childlessness of advanced civilization. The starkness of our unchosen world of choice was discernible with intense clarity at the threshold between Grover’s Corners and Manhattan, between a world where it’s said that “people are meant to go through life two by two” and “tain’t natural to be alone,” and one in which we are surrounded by people but desperate to avoid the addition of one to the exclusion of imagined others. Both are unchosen ways of life to the people living them – one of commitments, the other of endless choice. Both inevitably give rise to discontents, but our choiceless culture of choice makes discontent a way of life.

Very nice Patrick and very nice observations. I ve often thought about “Friends” being a tragic symbol of our post modern world though its title was misleading. It should have been called “Groupings” since friendship is hardly an appropriate description of the relationships that was portrayed. Such it would seem to me is the way of things in a civilization that is in old age. Here is a nice quote from Oswald Spangler regrading your observation that it is childless.

“When the ordinary thought of a highly cultivated people begins to regard “having children” as a question of pro’s and con’s, the great turning point has come. For Nature knows nothing of pro and con. Everywhere, wherever life is actual, reigns an inward organic logic, an “it,” a drive, that is utterly independent of waking being, with its causal linkages, and indeed not even observed by it. The abundant proliferation of primitive peoples is a natural phenomenon, which is not even thought about, still less judged as to its utility or the reverse. When reasons have to be put forward at all in a question of life, life itself has become questionable. At that point begins prudent limitation of the number of births. In the Classical world the practice was deplored by Polybius as the ruin of Greece, and yet even at his date it had long been established in the great cities; in subsequent Roman times it became appallingly general. At first explained by the economic misery of the times, very soon it ceased to explain itself at all. And at that point, too, in Buddhist India as in Babylon, in Rome as in our own cities, a man’s choice of the woman who is to be, not mother of his children as amongst peasants and primitives, but his own “companion for life,” becomes a problem of mentalities. The Ibsen marriage appears, the “higher spiritual affinity” in which both parties are “free”–free, that is, as intelligences, free from the plant like urge of the blood to continue itself, and it becomes possible for a Shaw to say “that unless Woman repudiates her womanliness, her duty to her husband, to her children, to society, to the law, and to everyone but herself, she cannot emancipate herself.”

The primary woman, the peasant woman, is mother. the whole vocation towards which she has yearned from childhood is included in that one word. But now emerges the Ibsen woman, the comrade, the heroine of a whole megalopolis literature from Northern drama to Parisian novel. Instead of children, she has soul-conflicts; marriage is a craft-art for the achievement of “mutual understanding.”

Some perceptive comments, Patrick; many thanks. “Our Town” is, of course, more than just the nostalgia trip that some presentations milk it for; there is a bite to it, a recognition of costs and an awareness of the ultimate vanity of most of our choices, in the end. But the fact that it at least respects and valorizes the full range of choices–rather than stacking the deck in favor of cosmopolitan ones–is what makes it a worthy entry into the small set of Front Porch classics.

Our Town is my favorite play. When Emily goes back to relive her 10th birthday in hope that everyone will just for once appreciate one another and savor their time together, and instead everyone is too busy just leading their lives to notice, just crushes me. I think about that moment just about every day when I’m with my loved ones.

I don’t know why, even though I grew up in a small town (called by some the Mayberry of the West) I always found “Our Town” terribly depressing. I always left the theater soaked in a sort of marinade of the pointless waste we all make of life and living. I suppose it at once offers the practical hedonist’s one hope, but doesn’t tell how to get there and presents only a group of people who failed to do so.

But isn’t it telling that a play like “Our Town” is still put on and even, in of all places, Greenwich Village?

“Emily Webb and George Gibbs – speak haltingly and charmingly of their growing affection and love, in terms almost unrecognizable not only in New York City, but one dare says in the world that we increasingly inhabit”

How could a would-be dramatist make the unrecognizable comprehensible across cultural chasms like these? People can somewhat understand the settings and plots of Shakespearean plays. Yet the presentation in new works of the customs and views of our recent ancestors is very neglected.

Roger S. –

I’m confused as to why you think a commitment to motherhood and family responsibilities is incompatible with a drive toward “mutual understanding” and having a husband who is one’s “companion for life.” From a Biblical perspective, God obviously designed marriage as the appropriate forum for reproductive activity and the raising of children, but it also appears that He designed it for companionship (“it is not good for the man to be alone.”) That doesn’t quite square with the view of woman as mother – and only mother. Furthermore, I may be misinterpreting you, but your idealization of women as “primary” and “peasant” also seems to imply that education, philosophical reflection, and the like are not necessary either for women in general or for motherhood – which, I think, degrades not just women but the enterprise of motherhood itself.

I agree that the popular view of marriage (especially in Western, developed society) has undergone a dangerous shift away from concepts of responsibility and commitment and toward a sense that couplings are optional and fluid; however, I would argue that the risk of infidelity rears its head not whenever women (and men) put a high priority on companionship and mutual understanding, but when they reverse the proper order of things. In other words, one ought to seek mutual understanding and friendship with one’s spouse, rather than (when already married) seeking a partner with whom one thinks one can achieve such a relationship, whether or not that person is one’s spouse. The marriage is always prior, and yet faithfulness in marriage lies not only in avoiding sexual infidelity (although that condition, of course, must be fulfilled), but in fulfilling God’s design for marriage, which includes both openness to children AND some sort of companionship and emotional and spiritual support. Yes, that looks different in different cultures and situations. But I would argue that the second element is present no more and no less in two peasants working together to practice subsistence farming than in, say, two American city slickers working and volunteering in ways that reflect their shared values.

– KPE

Katherine

I don’t believe as the quote might intimate that motherhood and mutual understanding are incompatible. Heaven forbid. Moreover, I don’t think that Spengler was advocating a position regarding what marriage should or should not be. I think he was observing that a symptom of an aging culture is that it becomes childless, with motherhood becoming a secondary consideration in relationships rather than a primary one. I think that Friends and Seinfeld were fairly indicative of a cultural point of view that deemphasized family and placed value on individual autonomy and where childbearing was hardly thought about and a mere happenstance if it happened at all.

Speaking of the discontentedness of the choiceless culture of choice, here’s a lament of the tyranny of choice that argues in favor of the restlessness that that tyranny imposes.http://www.salon.com/life/coupling/index.html?story=/mwt/broadsheet/2010/04/14/tyranny_of_dating_choice

Last night, around 7 pm on the way to a job-site before a Wetland Hearing, I passed by one of the Private Schools in town and noticed the kids, 6,7, 15 to 16 playing or talking in a common outdoor area and it struck me how powerfully sad it is that we have so commodified ourselves that shipping our children off to school as a means to both free up our own time and “provide the best opportunities” to our children is deemed a respectable thing. I recall news of one student in a private school hearing about his parents impending divorce through the media and despite his trauma, the parent sent an assistant in a limo to deal with it.

What is at work in our presumed culture that we feel so blithe about the Faustian Bargains we make on the road to “success”. We do not seem to recognize that we learn as much from our children as they do from us. Everything in life is a holding pattern waiting for take-off into the glorious skies of material gain.

When the elite of a society treat children as essentially livestock to be fattened, one can assume that the Rules of the Abattoir are in effect. Cattle prods become the most useful tool…along with sharp knives.

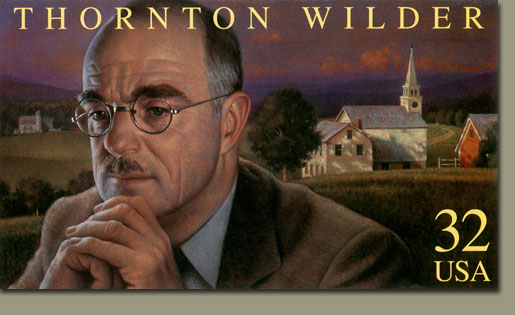

Although “Our Town” is the most performed play by an American, it is second to Wilder’s “The Skin of Our Teeth” as perhaps the best American play. His novel “Heaven’s My Destination” is the best thing he ever wrote, although his Great Novel is “The Eighth Day.” Wilder never lived in a town. He never lived among neighbors and friends. He was a peripatetic man, on the outside a perfect cosmopolitan who knew every city and mountainside in the world and knew no one person as intimately as Emily and George knew each other in such a short time. Wilder breathed classical and medieval and modern literature. He reduced it all to how we live in our hearts. He will transcend New York City and Grover’s Corners, but he never found peace.

What a treat to read people’s comments on my favorite play. When it was to be performed locally I and my husband took parts after the required auditions. It is the only play I ever care to be in but, oh, how wonderful to be there night after night, listening to the dialogue and watching the other actors play out those delicious scenes. Emily, looking at the moon and commenting to George. George being chastised by his father for not helping getting in the wood for his mother (I think of that as I carry wood upstairs), and feeling shame. Emily going back for that birthday party and crying to her family, “Look at each other …” Yes,I too, think of that at family gatherings. My part in the play was a woman at their wedding, and then later sitting in the cemetary. I’ve seen this play many times, and am always on the lookout for another chance, but will forgo this one. I live in Newport on the Oregon Coast. New York City is for visiting and watching plays, not for living. Thank you, John Willson for your info about Thorton Wilder. I hope he had at least moments of peace after writing a perfect line – he did several of those.

Comments are closed.