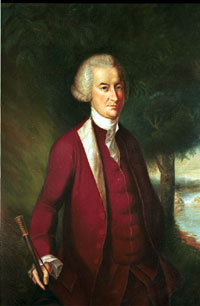

Hillsdale, MI. This handsome man is not one of the better known faces of the era that some people, for reasons that vary, like to call our “Founding” as a “Nation.” He died on February 14, 1808, and since then has inspired two (!) biographies–one by Charles Stille in 1891, the other by Milton Flower in 1983. At this rate, the next one is due sometime early in the next century. If you are interested in the life and times of John Dickinson of Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, you should read one of them pretty soon.

Had John Dickinson not been ill for most of the summer of 1787 (“I was much indisposed during the whole Term of the Convention.”), our Constitution would look more like the Articles of Confederation than it now does, and the Front Porch Republic may well be discussing different things. Dickinson wrote the first draft of the Articles, after he had refused to sign the Declaration of Independence, and later wrote a defense of the Constitution (The Letters of Fabius) that was much more intelligent and much more to the point of republican government than the celebrated and overrated Federalist Papers. He also freed his slaves, which no other public man of his age did, and ended his life as a republican who was skeptical even of the supposed decentralist Jefferson.

Helen and I lived for a week in Center City, Philadelphia, in 1993, researching John Dickinson’s thoughts about secession and nation-building. Most Americans don’t know that he refused to sign the Declaration of Independence for better reasons than Jefferson had to write it, or that he had made most of Jefferson’s arguments before the sage of Monticello had made them, or that he was celebrated by Sam Adams who published his “Liberty Song” in Boston even before Paul Revere’s ride, or that the King of England knew who he was long before he heard the name Washington. I had already written a little book, John Dickinson: The Letters of Fabius, but was convinced that there was more to tell.

Center City was, and is, the home of Philadelphia’s arts. It’s a beautiful place, and filled with what we must call, “alternate lifestyles.” I had never before seen gay restaurants or men wasting away in their suits as they tried to carry briefcases from a taxi to their apartments. Our hostess, the owner of the bread and breakfast that was our home for the week, was at first somewhat afraid of us (Christian midwestern middle aged married once, and darn, “conservatives”) but she warmed up, and did she ever know restaurants and plays! She was a dancer who had grown up in New York City and lived in the same building as Toscanini. The Library Company of Philadelphia, founded by Ben Franklin and his partners in the Junto in 1731, is at 1314 Locust St., just around the corner from our temporary home. It’s a little surreal: history, artsy….

On our third day in the library Helen nudged me and said, “Is this what I think it is?” She was holding in her hand the original handwritten copy of the Articles of Confederation. Dickinson’s handwriting was about as good as most physicians, who write prescriptions so that nobody will understand what they say. Despite being one of the richest men in the colonies, Dickinson had very limited access to paper, so he wrote on both sides of the page, and up and around the edges. I thought the holograph should have been protected somewhere in the National Archives, but there it was, and the librarian allowed me to copy it. For ten years I had teams of students translating it. I believe that I have the only authentic and original copy of the Articles in existence.

Later that week we found a letter from Dickinson to his daughter Maria, explaining why he freed his slaves. He wrote it in 1794, just about the time that the ultra-nationalist Hamilton was enthusiastically putting down the Whiskey Rebellion in the western part of the state that Dickinson had helped save from its original democratical constitution. Dickinson formally freed his bondsmen on May 12, 1777, almost a year after he had written the Articles, and fully four years before they were adopted as our first constitution. He said, simply, that the principles of self government and the rights of Englishmen under the Common Law that caused our secession had to be applied to all of us. In 1794 he told Maria that had he been feeling better in the summer of 1787 he would have prevailed upon his colleagues to face the problem of slavery, and not put it off in a Franklinian compromise because southerners like Charles Pinckney threatened to prevent a union from continuing to exist. We should have been courageous, he said; we will have to face the consequences of our lack of courage, he said.

Dickinson’s first draft of the Articles included provisions for an impost, which would have given the government an income, and subtle powers for the executive functions of the legislature that together would have made the convention of 1787 unnecessary. He signed off on the Constitution because he was convinced that a combination of the equality of the states (the Senate was his contribution to that frightful summer) and the “power of the people” would restrain what Hamilton and others hoped would become an English-style government. He also uttered the wisest and most prudent statement of the entire constitutional debate. On August 13, 1787, he said, “Experience must be our only guide. Reason may mislead us.”

John Dickinson lived long enough to know how right he had been. We need to learn which of our fathers to honor. Dickinson stands for the right combination of limited government, local loyalties, principled freedom, and the rule of law that republican government requires to survive. We write biographies of nationalists, and pay too little attention to the men who gave us our liberty.

“He also freed his slaves, which no other public man of his age did…”

In point of fact, one should also remember Robert Carter III as well.

http://www.amazon.com/First-Emancipator-Forgotten-Robert-Founding/dp/0375508651

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Carter_III

Yes, but that was in the good old days when problems were meant to be faced by government rather than created and mined for billable hours or campaign contributions. Thanks for this brief intro Willson, it demands a fuller look and so we’ll have to satisfy ourselves with one of those dog-eared old biographies.

Dr. Willson,

This is an intriguing post, but it seems incomplete. You raise interesting questions about Dickinson, but you do not answer them. For instance, what were his reasons for refusing to sign the Declaration of Independence?

Perhaps you could write another post explaining Dickinson’s political outlook a little more thoroughly.

Actually there is one more book on Dickinson (although not precisely a biography):

http://www.amazon.com/Quaker-Constitutionalism-Political-Thought-Dickinson/dp/0521884365

Good post. Readers might want to know that Mark David Hall and I conducted a survey last year naming the top “Forgotten Founders.” John Dickinson finished 7th, overall. We also published a small and very reader-friendly book called _America’s Forgotten Founders_ profiling the top ten and identifying a wider group as well. Copies can be found on amazon and at http://www.butlerbooks.com with a second edition coming out from ISI Books in 2011.

Finally, someone who agrees with me that the Federalist Papers are overrated!

So which of our founding fathers do we need to honor? [and which ones are honored inappropriately?]

Gary Gregg,

That’s cool that you did such a survey. If Dickinson finished SEVENTH, who in the world would have been ahead of him? He was the brightest, the wisest, the most decent man of his generation. Washington, of course, was our “father,” but the rest of them are ranked only by ideologues.

Matt G: A new one on me. Thanks for the Robert Carter III info.

Mark Howard: I have always thought that the little guy (Madison) and the BIG guy (Knox) and almost all the ultranationalists (like G. Morris) are overrated. Among the nationalists I like Arthur St. Clair the best. John Witherspoon gave us our wonderful liberal arts colleges, which we didn’t ruin until after WWII.

Matthew Gerken: I’m glad to agree with you. Tell us all why you think the FP are given too much credit.

Mr. Gregg,

With all due respect, how do you — or, anyway, your survey participants — list Thomas Paine amongst the top-ten forgotten Founders, but not the liquor-loving, loquacious Luther Martin?

Prof. Willson,

Thanks for this wonderful introduction. I’d like to second Stephen: Please, tell us more!

Mr. Origer,

You will have to ask the survey participants that responded and took part in our little survey. Professor Hall and I had no substantive say in the results, we just asked the questions. Here is more:

Sept. 13, 2008

Poll reveals America’s forgotten founders

George Washington didn’t create country all by himself, survey shows

LOUISVILLE, Ky. – Ever hear of James Wilson? George Mason? How about Gouverneur Morris?

If those names don’t ring a bell, it’s no wonder. All three men helped shape the United States when it was new in the late 1700s, but hardly anyone today knows who they were or what they did.

Political scientists Gary Gregg and Mark David Hall think that’s a shame, so they undertook a survey to identify the nation’s most important early patriots. They announced their findings today at the University of Louisville in the form of a top ten list, “America’s Forgotten Founders,” in anticipation of Constitution Day on Sept. 17.

“Everybody remembers George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, but many other founders of our nation have gone largely unrecognized over the years,” Gregg said.

Gregg and Hall asked more than 100 historians, political scientists and law professors to nominate people who played a major role in the nation’s founding “but who have been unjustly neglected by history.” They culled the list of 73 nominees down to the 30 cited most frequently, then gave that list to the scholars and asked them to rank the top ten.

Wilson, a Scots immigrant who helped draft the Constitution and who served as one of the first U.S. Supreme Court justices, topped the list. Mason, who shaped the Bill of Rights, came in second, while Morris, America’s first overseas secret agent, placed third.

Rounding out the list were John Jay, Roger Sherman, John Marshall, John Dickinson, Thomas Paine, Patrick Henry and John Witherspoon.

Although most nominees were white males, Nanye-hi, a Cherokee woman who urged peace with whites, and Phyllis Wheately, an African American poet born into slavery, also were contenders.

“We were surprised and encouraged by the wide range of names suggested,” Gregg said.

Gregg directs UofL’s McConnell Center, an academic program that prepares students to be leaders. Hall is Herbert Hoover Distinguished Professor of Political Science at George Fox University.

Thanks for the reply, Gary. Either way, I’m glad that something of this nature was done.

Was John Randolph of Roanoke on the list Greg? He is by far my favourite of the early US patriots along with John Adams.

Ugh Thomas Paine please, I suppose he appeals to liberals and secularists but I find him the most overrated of all the FFs, only his Agrarian Justice can I recommend.

John is John Adams a nationalist in your opinion? If he is then he is most certainly my favourite and perhaps my favourite US founding father. Fisher Ames is also an interesting nationalist, simply for his thoroughly cantankerous and morose attitude. He has something of the wonderful Dr.Johnson about him.

I’d actually heard of Dickinson before, mostly in a work I read on American Tories. He had a long running dispute with another Pennsylvanian figure whose name escapes me, leader of the proprietary party if memory serves. He seems like a very interesting figure and I must learn more about him.

I’ve been reading a lot about Quakers recently. I’d come across Dickinson in the past, but I had forgot about him. I think the Quaker influence on him is obvious.

In his draft of the Articles of Confederation, he used gender neutral terminology, “person” instead of “man” as was used in the Declaration of independence. Only someone with a wussy liberal Quaker upbringing would do that. LOL Those Quakers loved their equality.

Quakers were also a bunch of liberal peaceniks. Dickinson couldn’t get fully onboard with Quaker pacifism (no if, and, or buts), but he maintained a strong pacifist inclination. Although he believed in defensive war, he seems to have had a very restricted notion of what morally justified this self-defense principle. He supposedly refused to sign the Declaration of Independence because he thought it ould lead to war. Even when the army rioted in demanding pay, he refused to have them violently put down and instead sought a peace resolution.

I’ve seen many people refer to hIm as a conservative. He may have been a small ‘c’ conservative, but as far as that goes he was also a small ‘l’ liberal. More accurately, I’d describe him as a principled moderate, a centrist of sorts for those revolutionary times.

I should clarify something.

I never said that John Dickinson was a Quaker. I said he had a Quaker upbringing. Both his parents came from Quaker families that involved several generations of Quaker membership. He married a woman who was a Quaker, was raised a Quaker and came from an extended family of Quakers.

Dickinson spent his whole life intimately involved with Quakerism and surrounded by Quakers with whom he regularly interacted and corresponded. He later in life had other influences, but those early life influences tend to have deep impact on people. I think anyone can understand that from their own experience. Later influences usually never affect us as powerfully.

I don’t know the specifics of these influences, as I’m not an expert on the subject like Calvert. Then again, I’ve never seen anything saying he denied his entire Quaker upbringing. I doubt it considering he willingly chose to marry into a Quaker family. Also, he did continue to write about Quakerism and so it apparently was part of his thinking, even if he disagreed on absolute pacifism.

As for pacifism, he did have strong leanings toward pacifism. He believed pacifism should be sought before all else and that violence should only turned to as a last resort self-defense, but he went even further than this. If the opportunity to avoid violence presented itself, he actively sought it even if others saw violence as justified.

If anyone is interested to learn more about this, I’d recommend Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson by Jane E. Calvert. That probably is the most detailed analysis of the subject ever written. Calvert is a history professor and Director/Editor of The John Dickinson Writings Project. The entire text of her book can be found here:

http://worldtracker.org/media/library/College%20Books/Cambridge%20University%20Press/0521884365.Cambridge.University.Press.Quaker.Constitutionalism.and.the.Political.Thought.of.John.Dickinson.Dec.2008.pdf

Here is a response Calvert wrote:

http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8080332

“Likewise, Levy reveals that he hasn’t read carefully any o f Dickinson’s work when he claims he “continually legitimate[d] violent revolution.” Not once, in any of his writings, public or private, did Dickinson advocate revolution for America. As I make clear—dealing thoroughly with the apparent contradictions in Dickinson’s thought—he believed in defensive war (192, 233-35), something quite different from revolution, which should happen only rarely (220). He could support the French Revolution (which is beyond the scope of this study) because the French, unlike the British, didn’t have a constitution to protect them.”

Another interesting comment by Calvert about a letter Dickinson directed to the Paxton Boys:

http://vi.uh.edu/pages/buzzmat/Radhistory/radical%20history%20articles/John%20Dickinson%20to%20Paxtons.pdf

“When he wrote, Dickinson was a member of the assembly, sympathetic to Quaker interests, and actively involved in managing the crisis moving from the frontier toward Philadelphia. His letter highlights the difficulties Quakers faced in balancing their political ideals with the realities of governing people who did not share their commitment to pacifism and friendship with the Indians. Specifically, it shows how Dickinson, as a non-Quaker, used means that Quakers politically and theologically could not in order to realize their hopes that “the Disturbances might more easily be quieted than by harsher Methods.”2”

The following are some other explanations of Dickinson’s views:

http://dickinsonproject.rch.uky.edu/biography.php

“Dickinson’s religion was an important factor in his life. While he never became a member of the Society of Friends, citing his belief in the “lawfulness of defensive war” as his reason, his personal and political priorities and behavior were strongly shaped by Quakerism.”

[ . . . ]

“His fundamental belief was that popular defense of rights should not destroy constitutional unity and that amendment of the laws was possible through civil disobedience. He adopted this view from the Quakers, who did not believe that violence or revolution were legitimate options to resist government oppression. He, like they, believed that the civil constitution was both perpetual and amendable. He therefore counseled negotiations, boycotts, and peaceful breakage of the offending laws with the aim of having them repealed.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dickinson_(Pennsylvania_and_Delaware)#Drafting_of_the_Articles_of_Confederation

“Dickinson prepared the first draft of the Articles of Confederation in 1776, after others had ratified the Declaration of Independence over his objection that it would lead to violence, and to follow through on his view that the colonies needed a governing document to survive war against them. At the time he was serving in the Continental Congress as a delegate from Pennsylvania. The Articles of Confederation he drafted are based around a concept of “person”, not “man” as was used in the Declaration of Independence, although they do refer to “men” in the context of armies.[9]”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dickinson_(Pennsylvania_and_Delaware)#Continental_Congress

“When the Continental Congress began the debate on the Declaration of Independence on July 1, 1776, Dickinson reiterated his opposition to declaring independence at that time. Dickinson believed that Congress should complete the Articles of Confederation and secure a foreign alliance before issuing a declaration. Dickinson also objected to violence as a means for resolving the dispute.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Dickinson_(Pennsylvania_and_Delaware)#President_of_Pennsylvania

“Perhaps the most significant decision of his term was his patient, peaceful management of the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783. This was a violent protest of Pennsylvania veterans who marched on the Continental Congress demanding their pay before being discharged from the army. Somewhat sympathizing with their case, Dickinson refused Congress’s request to bring full military action against them, causing Congress to vote to remove themselves to Princeton, New Jersey.”

I mentioned the aspect about gender neutral language. That is hard to explain without looking to a Quaker influence. Gender neutral language was highly unusual back then. There was no other major religious group I can think of besides Quakers that saw as much equality among the genders.

Another example of where Quaker influence could possibly be seen. Dickinson saw people getting caught up in passionate rhetoric and lofty idealism. He thought that was unhelpful or dangerous for it caused people to get carried away by emotion and mob thinking or something like that. This seems to relate to the Quaker preference for a quiet relationship with God and honoring God’s Truth with simple language. Quakers wanted to calm the passions, not increase them.

It isn’t any single factor that demonstrates the Quaker influence in Dickinson’s life, his words and actions. It is all these examples put together combined with the assessment of experts in the field such as Calvert. Both Calvert and I could be wrong, but it seems unlikely that there was no Quaker influence on Dickinson. That would be truly bizarre for him to be so surrounded by Quakers and not be influenced.

Actually, I’m not extremely attached to the interpretation of Dickinson being Quaker influenced. It makes sense to me, but it doesn’t bother me if someone wishes to interpret it otherwise.

The only reason I have much interest in Dickinson is because of the Quaker connection. In general, Quakers have had massive influence on American society. That certainly can’t be doubted (see David Hackett Fischer and Colin Woodard).

And the only reason I have much interest in the Quakers is because they founded the basic culture of Pennsylvania and much of the Lower Midwest. As a Midwesterner, this is my specific interest.

Dickinson just relates indirectly, but it is a very interesting connection.

Knowing about the history of Quaker culture, these connections just jump out to my mind. I see something like the Articles of Confederation and I immediately see how that perfectly fits into the Quaker political practices. Quakers mistrust big centralized government and prefer instead more localized self-governance. I also can’t help but consider the fact that Dickinson, as a politician in Pennsylvania, would have known the Quaker political system inside and out.

However, to others, these connections don’t jump out. I don’t know what to say. I would recommend reading about Quaker history because it is very interesting and quite relevant. The more I learn, the more I see the connections.

Comments are closed.