Rock Island, IL

It is difficult not to credit the works of Kingsley Amis, notwithstanding his contempt for the things that many of us care about, if not hold dear. One thinks of the Church, for example, or belief in God, or morality.

The reasons it is difficult are perhaps various: he is a funny novelist, and funny isn’t easy to do; he doesn’t despise his characters (as his son Martin apparently despises his), though neither does he wholly adore them; he recognizes buffoons and knows how to lampoon them.

Lucky Jim, perhaps the first of the send-ups of academic life, is still one of the best. Stanley and the Women, Difficulty with Girls, One Fat Englishman—each one can make you fall off your chair laughing. The first of these has one of the best descriptions of a hang-over you’ll ever read (I paraphrase part of it: ‘he felt as if a small animal had used his mouth first as a latrine, then as a mausoleum’), and the last a hilarious description of a man in the clutch trying (by mentally working on his Latin declensions and then reciting Chaucer) to outlast his lover. I think Girl, 20 is also on my shelf, and what other books I don’t remember just now as I tap away in a hotel “business center” beneath a sign asking me to be polite and limit my time on the computer to thirty minutes.

It is true that Amis sometimes avails himself too readily of drink. I don’t mean Amis personally, though it appears he did that aplenty. I mean that in order to get his characters to do what he wants them to do—and often this means behave badly—he gets them drunk quickly. I seem to recall his admitting to this very trick in his memoir, which is a fun read if you’ve read his fiction or the poems he selected for that collection of “light verse,” published by whom I disremember at the moment. Oxford, I think.

(The memoir has some wicked things to say about what it was like to study under Tolkein–‘torture’ pretty well sums it up–and also about Wheaton College’s Wade Center, which Amis characterizes as a silly shrine to the likes of Lewis, Muggeridge, and Chesterton.)

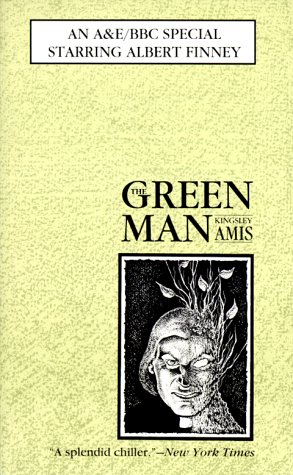

But I was surprised to find much of Amis’s contempt for the usual things muted, if not reversed, in The Green Man. Until two weeks ago it was the one book by Amis on my shelf that I’d not read, and so I took it with me on my sojourn to England’s green & pleasant land to help me forget for a while that I was in a chair above the Atlantic ocean.

The biggest surprises, at least to me, are the exorcism near the novel’s end and the attempt on the part of the main character, Maurice, who is a selfish drunk, to turn his life to good account for the benefit of someone else.

This is Amis, mind you.

The vicar called upon to perform the exorcism doesn’t believe in anything and he doesn’t even know how to execute the rite. He discovers only after arriving to the haunted site that he’s supposed to bring holy water with him, and then is pleasantly surprised that his prayer book actually provides a rite for the blessing of water.

And, of course, he’s a poofter, as the Brits of Amis’s generation called such men.

But one of the funniest parts of this novel is that two women, who will first consent to an orgy with Maurice and later leave together to give lesbianism a try, must instruct the vicar on the finer points of his vocation. (One of the women is Maurice’s wife.)

I pick the story up at the point where Maurice is telling his wife and mistress that he and the womanish Rev. Tom Rodney Sonnenschein have been discussing “God’s purpose.” The women, in a flat matter-of-fact unflappable way—and due in part to their own greater unbelief—in a few deft verbal motions dismantle the collared fool, who has obviously swallowed, hook, line and sinker, the most banal of all secular discontents:

“Mr. Sonnenschein has been explaining to me about God’s purpose,” I said.

The rector gave a quick wriggle of one hip and the opposite shoulder. He said deprecatingly, “Oh, well, you know, that sort of thing’s bound to come up from time to time in my field.”

“What is God’s purpose?” asked Joyce, using the interested, far from friendly, wholly reasonable tone that I had learnt to recognize.

“Well, I suppose one might start to answer that by saying what it isn’t. For instance, it’s nothing to do with getting hot and bothered about the state of one’s soul, or the resurrection of the body, or the community of saints, or sin and repentance, or doing one’s duty in that state of life into which it has pleased—”

I had been looking forward to an exhaustive list of what God’s purpose was not; Joyce, however, cut in. “But what is His purpose?”

“I should say, I would say that what … God wants us to do”—there were sneer marks round the last phrase—“is to fight injustice and oppression wherever they are, whether they’re in Greece or Rhodesia or America or Ulster or Mozambique-and-Angola or Spain or—”

“But that’s all politics. What about religion?”

“To me, this is … religion, in the truest sense. Of course, I may be wrong about the whole thing. It isn’t up to me to tell people what to think or how they ought to—”

“But you’re a parson,” said Joyce, still reasonably. “You’re paid to tell people what to think.”

“To me, I’m sorry, but that’s a rather outmoded—”

“Mr. Sonnenschein,” put in Diana, chopping it up so sharply that it sounded a bit like one of those three-monosyllable Oriental names.

The rector waited quite a creditable length of time before saying, “Yes, Mrs. Maybury?”

“Mr. Sonnenschein … Would you mind frightfully if I were to ask you a rather impertinent question?”

“No. No, of course not. It’s a—”

“What- …’s the-point of somebody like you being a parson when you say you don’t care about things like duty and people’s souls and sin? Isn’t that just exactly what parsons are supposed to care about?”

“Well, it’s true that the traditional—”

“I mean, of course I agree with you about Greece and all these places, it’s absolutely ghastly, but everybody knows that already. You must simply not take offence, please not, but lots of us would say it’s not up to you in your position to start sounding like, well …”

“One of those chaps on television doing a lecture on the problems of today and freedom and democracy,” said Joyce, even more reasonably than before.

“We don’t need you for that, you see. Mr. Sonnenschein …”

“ … Yes, Mrs. Maybury?”

“Mr. Sonnenschein, don’t you perhaps think that when everybody’s so tremendously, you know, ahead of everything and knowing it all and everything, then it’s a bit up to you to be jolly crusty and jolly full of hell-fire and sin and damnation and jolly hard on everybody, instead of, you know …?”

“Not really minding anything like everybody else,” said Joyce. She drained her sherry, looking at me over the top of the glass.”

“But surely one must tell the truth as one sees it, otherwise one—”

“Oh, do you really think so? Don’t you think that’s just about the riskiest thing one can possibly do?”

“You can only think you know it, probably,” finished Joyce.

“Yes. Well. There we are. I must go and see the major,” said the man of God, so rapidly and decisively and so immediately before his actual departure that seeing the major (even though there was a retired one actually present) might have been a Sonnenschein family euphemism for excretion.

This is probably as good as Amis can do by way of crediting the Church: send up the social and political substitutes that alone are more ridiculous and preposterous than faith itself.

But what struck me as I read this scene in a chair above the Atlantic is how it gets things exactly right: the riskiest thing for someone sworn to uphold the teachings of a living body larger, older, and wiser than himself is to tell the truth as he sees it—that is, to trust too much the devices and desires of his own heart, as the Prayer Book would have it.

Once you get that straight you might have a chance of thinking of the priesthood in its ultimate terms:

Like marriage (to which it is analogically related in many ways), the priesthood is not a “field,” as Rev. Sonnenschein calls it. It is not a job, not a profession, not an “opportunity.” It is in fact a kind of martyrdom.

And (just to localize this a bit) that martyrdom is possible only in a place. Indeed, in a place martyrdom is likely. It is probably even proper. The way to avoid it is to go on about Greece and Mozambique and everything but what and who are at hand.

The “vision of God” in the novel is, as I recall, more or less a Hindu thing, really, though I doubt that Amis thought of it thus: that history is the play of Brahma. Brahma, of course, has a savage aspect (Kali) and so does Amis’s sophisticated youth of the vision (=God).

Religion? Priesthood? Why bother with clergy if you can find out truth for yourself?

At least ordain women and the openly gay to the clergy; why don’t the orthodox and the catholics follow simple justice-love and do what the Mainline Protestants have done?

Comments are closed.