Rock Island, IL

You don’t have to think much of Allen Ginsberg to credit a question he raises in one of his better-known works:

“America,” he says in inebriate apostrophe, “how can I write a holy litany in your silly mood?”

The ambient (or maybe, by then, residual) McCarthyism of the time turned Ginsberg into a man of finite jest for a little over a hundred lines. Toward the end of “America” he mocks the fear-mongers:

Them Russians them Russians and them Chinamen. And them Russians.

The Russia wants to eat us alive. The Russia’s power mad. She wants to take our cars from out our garages.

Her wants to grab Chicago. Her needs a Red Reader’s Digest. Her wants our auto plants in Siberia. Him big bureaucracy running our fillingstations …

and so on until, after a slight modulation, he says, not altogether seriously, but also not without buckshot, “America, this is quite serious.”

America, this is the impression I get from looking in the television set.

America, is this correct?

There’s some incredulity in that last line (which isn’t the last line of the poem—or “poem,” if you prefer), and it seems to sound the right note in a piece in which the speaker had asked earlier, “America, are you going to let your emotional life be run by Time Magazine?”

(Ginsberg wasn’t the sanest of men, but it would please him, I think, to learn that the editors of Time will soon be publishing an edition for adults.)

As far as poets go, Ginsberg isn’t exactly my cup of sack, but I found he wouldn’t go away recently, even though he’s dead. I thought I saw him looking over a few shoulders this past weekend, a weekend behind us at last, still wondering in his way whether a holy litany can be written amid the ambient (or is it residual?) silliness of a people increasingly incapable of ceremony, propriety and meaningful remembrance.

It was hard not to see a great deal of dime-store sympathy and self-congratulation in those solemn moments just before kick-off. It is never easy to believe that made-for-TV tributes, whether brief or insufferably long, achieve their emotional pitch by means legitimate. But it is also dangerous to accuse others of sentimentality when maybe you yourself have lost all capacity for sentiment.

But then again that’s not quite it, is it—not really. Rather, it’s that we’re bumping up against matters of scale once again here. We’ve been asked to assemble our small talents and even smaller thoughts and do something significant ten years after a grim day we still only slenderly understand, if at all. We’ve been asked to put aside our pervasive cultural silliness and accomplish something of real gravity that can’t be done well on a national scale.

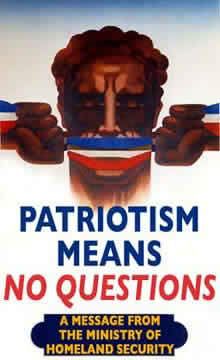

And since it can’t be done well on a national scale we find ourselves clinging to the slogans that simplify, and in simplifying trivialize, the task: “We Will Never Forget”; “These Colors Don’t Run”; “Support Our Troops”; “God Bless America.” They don’t mean enough, these slogans. About all they can do is invite us to pledge allegiance to an abstraction.

I would not be misunderstood. Love of country is something of which we must all be capable. But we must be capable of it in ways suitable to creatures whose habitation is a countryside, not a country. We are not giants, after all. We are men and women.

What happens when the slogans invite us to love a country at the expense of a county? A town? A neighborhood? Many there be who shout from the grandstands U-S-A ! U-S-A ! but have no idea where they are; some don’t care where they are. So peripatetic are they that their love has no real object. There is no branch for that nightingale to light upon.

Am I questioning the loyalty—the patriotism—of people I don’t even know?

No, I’m not. For one thing, “loyalty” and “patriotism” are words that hardly signify anymore, and at any rate I’m with Dr. Johnson: “patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” For another, I’m trying to say something more to the point—something about love and its proper objects. I don’t think a nation is such an object.

Love of a particular place, love of particulars, is always difficult. It is a high order that makes high demands on us because its object is always before us. It can ask, as a nation can’t, not really, “do you love me?” And it can look you in the eyes and wait for an answer.

Oh, the nation can ask you to “make the ultimate sacrifice,” but that’s because its vocabulary seldom extends beyond the lexicon of war and “Mission Accomplished” and “them Russians and them Chinamen.” Ginsberg was right to ridicule it. Love of a place enlarged beyond the scale of our competence is an easy love made for easy lovers. This is the nature of abstraction. Love for it comes cheaply, and usually without responsibilities anyone can point to beyond voting and singing the national anthem in the coliseum before the bloodletting begins.

So it is with women (if I may be permitted). Loving women is easy. You don’t have to worry about making a single one of them happy. But loving a woman is not easy, for a woman will not suffer your mouth to speak to her in the language of greeting cards. She requires more of you than the domestic equivalent of a little jury duty every couple of decades. She will be spoken to in the particular language of love particularly suited to her. And she will expect to be loved—by you.

A nation can make no such demands, and where there are no such demands love will always be easy. You can love an abstraction without ever having to enact love at all. (In the case of all women you can do it from behind the bushes, and some do.) The reason you don’t have to enact it is that you can’t enact it, nor can it be loved. It is too big for you to know where to love it—until you know where you are.

But once you know that you can begin to love. Until then you’ll welcome into your “living” rooms the talking heads who, loving an abstraction, spread a pestilential hatred and blast a people into profound ignorance. Of this I am quite certain.

There’s a grim joke going around that I’m going to risk telling:

“Knock, knock.” “Who’s there?” “9/11.” “9/11 who?” “You said you’d never forget!”

It would be difficult to find any humor in this if you were still mourning, ten years later, the loss of a son or daughter. I fully acknowledge that. But the object of its satirical jab is nothing less than our immense capacity in times of great pitch and moment to surrender all thought to the sloganeers. If we wish to be a people capable of ceremony, propriety and meaningful remembrance, we’re going to have to resist prefabricated thought. We’re going to have to refuse to write our holy litanies in silly moods. And we’re going to have to enact a particularizing love in particular places, not in the any places where the scoundrels are taking refuge.

Ten years ago I was walking up the stairs to teach a class on revenge tragedy and the insane logic of retributive violence that governs much of it. One of the towers had already fallen, and I didn’t even know it yet. By the time the lecture was over and the classroom empty, all the mischief had been accomplished. I walked down the stairs to find a crowd assembled around a television that had been wheeled out into a hallway. About an hour later a colleague, upon hearing the news, said without missing a beat, “You know what this means, don’t you? It means war.”

The insane logic of retributive violence governs more than just revenge tragedy.

Since then, especially at times when national attention and sentimentality are high—I mean at sporting events—I think of the NBA All-Star game in 1991. We were engaged at that time in a desert war we were calling a “storm,” which, as most people know, is an act not of man but of nature and so is nobody’s fault. You might say that, being a natural cataclysm, it comes with its own metaphysical sanctions. Maybe some people remember who won that meaningless basketball game. But many, I think, will remember hearing one of the most moving national anthems ever performed—the solemn wordless Hornsby-Marsalis rendition. And, notwithstanding the blank visages of some of the athletes, and the slogans all around, there was something there to outdo the Ginsberg apostrophe, a radiant sobriety in the arena and a high seriousness in the music. It wasn’t a war-cry. It wasn’t a remastered version of that absurd “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” It was an elegy.

Beautiful. Thank you.

Mr. Peters, I always enjoy your essays. I am curious, though: what would be the proper response to a military (or quasi-military) attack on our country, wherever it may be, if not “retributive violence”? What more prudent course of action should one take?

Its difficult to discern a cogent point in this essay. But perhaps its meant to be nothing more than a look into your various emotions and aesthetic predispositions. At any rate the following is intriguing:

“We’ve been asked to assemble our small talents and even smaller thoughts and do something significant ten years after a grim day we still only slenderly understand, if at all.”

Why should anyone believe this in the slightest? Its a big assertion but you support it with nothing.

“What happens when the slogans invite us to love a country at the expense of a county? A town? A neighborhood?”

How bizarre. Why should anyone believe that patriotic slogans make such an invitation?

“The insane logic of retributive violence governs more than just revenge tragedy.”

How does this square with your recently penned, violence ridden revenge fantasy involving Wall Street CEO’s and local organic farming. It is really difficult to believe that all of that carefully crafted venom was just a joke in the service of spreading Kunstler’s derivative point that “Our farmland is woefully underpopulated.”

Oh cripes here we go again with the flogging of JHK. James has written the definitive commentary on the hollowing out of American Purpose as depicted by our shoddily built and atrociously designed constructed environment. Not many have matched him, let alone done better. He’s got pith and moxy and this kind of thing is useful in combatting our slouch into built Gomorrah. If anyone ever put up a chart simply tabulating the money spent on our various strip malled excrescences vs. lasting built landscape over the last 35 years, only the daftly mad would find it agreeable. Well, I exaggerate, perhaps the American Homebuilders Association would muster a proper support after photo-shopping out the foreclosure signs.

So too do we have the various ignorami of the fat continent rebuking the notion that our 9/11 Memorials are materially much more than a ritualized kabuki of Empire Remorse.

Watching the names recited by relatives, in front of a uniformed soldier or other Hessian is a unique immersion into the complicated pathos of this Securitized Age. Mock-Securities and Security, how nice for us. With all this security talked about, we must, however, be satisfied with bupkus in the security department. In fact, we might flog out and dust off the old adage of “Separate but Equal”. We inhabit a nation vigorously engaged in the traffic of half truths and the quick rise of another cockeyed Texan Presidential aspirant only gives credence to the wisdom of a “cooling off period” statute for gun purchases. But then, I already own em.

Individuals are caught in the crossfire of empire but when we stage the funeral these days, there must be an elaborate parade of National Glory to legitimize the very personal and far more important familial loss. It is a damnable dirty business when avenging personal loss is transformed into the arcane arts of “Extraordinary Rendition” or Drones over the Hindu Kush controlled by teenagers sitting at a high tech desk in Colorado Springs.

The study of Semiotics is fine as an academic endeavor but when it is put in service to the State, we arrive at the kind of totalitarian morbid theatre that has been the calling card of every failed empire in history.

Dammit but I cannot locate either my Devil’s Dictionary nor Abbey’s little tome of piquant aphorisms but I shall attempt one of ole Ed’s best:

“the problem with most politicians is that they cannot spell the word sh*t even though their mouths are full of it”.

Farmland is underpopulated in this lovely bit of real estate…or disjointedly populated because we have forgotten that agriculture is husbandry and a unique occupation of human stewardship. Man, at present, thinks himself an impervious grand exploiter. With 26″ of rain in 3 weeks in my own particularly farming-abandoned province, he shall soon see his presumptions gone a tad moldy

Nationalistic Patriotic slogans are the most effective amnesiac for local concern ever invented. The record is clear, definitive. Perhaps the doubter might break off and chew any sanguinary decade in the twentieth century to remind them.

By the way Peters., “amnesiac apostrophe”……nice one.

“Its difficult to discern a cogent point in this essay.”

It’s “it’s,” O Ye of the Cogent Point.

Great essay.

Thank you, DW Sabin, for that wonderful Ed Abbey quote. I’ll be using it with some local friends whenever possible! The essay made several cogent points (and I had relatives in Manhattan, though not in the Twin Towers, that day). The war on Iraq had nothing to do with avenging the deaths of those who died on 9/11, some of whom weren’t even Americans, but rather was a PNAC project of the neoconservatives. They likely were nowhere to be found near the Towers that day (I remember a prominent law firm in the Midwest (supporters of Governor Kasich more recently, no doubt, and I know they supported the military retaliation for 9/11), whose partner-in-charge made haste to leave Manhattan after the planes hit and ended up renting a U-Haul truck in New Jersey. His biggest complaint that day was not being able to get himself away fast enough – which proves Mr Peters’ point exactly – cheap love mouthed easily after the fact.

Comments are closed.