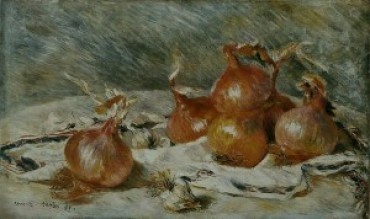

In The Supper of the Lamb, a delightfully odd book, Robert Farrar Capon suggests as an exercise in reality an extended session with an onion. “Once you are seated,” he suggests, “the first order of business is to address yourself to the onion at hand,” although overcoming the desire to quit out of sheer embarrassment is itself an accomplishment.

One notes, first, “that the onion is a thing, a being, just as you are.” One confronts the onion as a distinctly irreducible reality, as real as you are yourself, and thus there is a “mutual confrontation” between the two beings, a confrontation constituting, Capon suggests, a place. Not an abstraction like location, place is constituted by confrontation, by engagement, by attendance.

He asks us to tend to the onion, to at-tend and acknowledge or recognize the thing which is there in front of us. In doing so a place emerges from the event, which is “a Session, a meeting, a society of things.”

Session is an interesting term. It can mean no more than an allotment of time, as in a class period or time of a study group. But it also can denote governance, as “Congress is in session,” or as some Presbyterians have sessions by which to govern a church.

This double meaning—an allotment and a means of governance—is mirrored by a similar duality in the meaning of the word thing. In The Recovery of Wonder, Kenneth Schmitz reports that the OED documents an emphatic meaning of thing as whatever stands out as a separate reality distinguished from the totality of existence as well as a second meaning of assembly, a meeting place for governance and discussion of matters of import.

Session: an allotment, a granting of status to some dimension of time. Session: a mode of governance. Thing: a granting of status to some entity. Thing: a mode of governance.

When Capon suggests we confront the onion in a session between things, this is something rather odd and wonderful. Two things confront each other in a session. Two realities with status, each of them self-governing, grant to the confrontation a reality distinct from either, and grant to the confrontation some governance distinct from the self-governance of each.

This is why Capon suggests that the confrontation constitutes a place, a reality distinct from the two entities, and, moreover, suggests that the newly constituted place makes binding demands on each member of the place.

This is perhaps mere idle wordplay, the sort of nonsense a sane person does to avoid grading papers or doing the taxes, but Capon suggests the idleness has a point. Do not give up out of embarrassment, he requests, but stick it out. Shut the door if need be so no one sees you confronting an onion (anything will do, it needn’t be an onion).

Confront a thing, call a session to order. Now ask: does this thing and does this place bind me somehow? Ought I comport myself in a certain way to this thing and to this place because governance is at play here? Is there a law already at work in things and places and confrontations? Or may I do as I wish?

May I ignore this thing? May I break troth with this place? May I use the thing in any mode I wish, or are limits and order always already operative, already governing?

In his quirky way, Capon argues that the primary duty is to acknowledge the thing with delight, to “look the world back to grace” with delight in what is there. Boredom is heresy, for “as long as anyone looks” with delight, everything is seen in its weight and loveliness, and each thing compels.

Gerard Manley Hopkins writes of the man who “keeps all his goings graces.” The one looking things back to grace, delighting in the assembly of things, governed by the real and its weight.

The first duty is to acknowledge the value of the real. This is the first and primary duty from which the others follow. I’ll admit the poetic nature of my expression, but still it is the case. From a grasp of value comes all the other commandments.

If value is not grasped, the other commandments will be empty, burdensome, and Pharisaical. Poetry first, literature first, art first, philosophy first, and only then political action, only then movements and “assemblies” and declarations. First the love, then the struggle, else we lose both struggle and soul.

(There is, incidentally, quite a lovely piece to this effect by Elizabeth Corey in First Things, although requiring a subscription to view.)

As a nationally-known and highly-regarded culinary critic–or, no, wait: as the unofficial FPR food hack–I am very glad to see attention given here to The Supper of the Lamb. Robert Farrar Capon is not to be ignored.

Very Chestertonian, I will have to look this guy up.

Bed and Board by the same author is also good, but not as easy to find.

Comments are closed.