To paraphrase an observation of Chesterton on the subjects of poets, silence and cheese: Political scientists have been mysteriously silent on the subject of soap, or at least until now.[1 ] Less than obvious, therefore, at least to some, might be the connection between our political leanings and, say, our use of hand sanitizers, but that’s just one of the many interesting observations lifted by New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof from The Righteous Mind by University of Virginia psychology professor Jonathan Haidt.

“Anything that prods us to think of disgust or cleanliness,” Kristof reflects, “also seems to have at least a temporary effect on our politics. It pushes our sanctity buttons and makes us more conservative.” He notes also that a study at Cornell University showed that “students answered questions in more conservative ways when they were simply near a hand sanitizer station.”

I, for one, look forward to reading Haidt’s book for more interesting facts and observations on soap, skin, hair and politics. And, hopefully too, for a deeper understanding of these facts which isn’t there in the Kristof article. For an example of not only understanding but wisdom, however, in this now burgeoning niche of political science, the classic in the field remains: “Hair and the History of the City,” an essay contribution by Ivan Illich in the book Stirrings of Culture, (at least for those of us who cannot think of politics without thinking of the phrase “festering sore”).

In reading the encounters between doctors and patients in the past, it is clear that people were quite used to living with a festering sore. The doctor couldn’t do anything about it, and it is not that people didn’t mind – they simply didn’t go to the doctor to stop that festering. That is just what the human condition was. But it’s always difficult to speak with people about the fact that a festering sore, for example, was something you were stuck with and you had it. That was a pretty common statement until about 1908. Until that time, a patient had about one chance in two that the doctor could do something, anything at all, about the condition which they brought to the doctor. And, certainly in most of the world, it was quite obvious and normal to scratch and itch.

Are you following the implications?

I’m sure you’re following the implications.

What, in other words, has lead to the current hostility in politics, the current divide between the left and the right?

“Until recently”, according to Illich, “human beings never lived with their own surface out of contact with animal life. They shared their skin with other animals.”

That’s right. Until fairly recently, we shared our skin with lice, fleas, bed bugs and mites. It wasn’t “us” in simple opposition to “them,” or inside vs. outside. There was the now-excluded middle. There was the “us,” the “them” and the “us-them,” which was actually the hair on our bodies which was a home for these little critters, and the hair was a “commons.” Or, as Illich observes:

We no longer have commons. Today we have private and public spaces. As far as I know, “private” and “public” are concepts which are simply not applicable to a traditional city. The difference between the opposition of private and public is as a sharp line. That line is like we today imagine our body covering, our skin, a line dividing inside and outside. Hair, inhabited hair, belonging at the same time to inside and outside, makes the division more “fuzzy,” makes our life and animal life more alike; and when there is a commons, our life and the lives of others are experienced in common; life in the city, a gathering around a commons.

A connection between body hair and our Front Porches anyone?

Illich spent much of his career describing the vanishing domain of the commons, a reality the disappearance of which gives rise the strict separation between public and private and, analogously, a stronger breach between the left and the right.[2] According to this key, one would predict that somebody like Karl Marx was covered in carbuncles, furuncles and boils. And he was! One might also predict that John Locke, whose views on private property were much more, should we say “anal”, than, say, those of the sane Thomas Aquinas (a man who understood private property as well as the commons), would be a real progressive stickler for hygiene.[3] Eureka! (He was.) Whereas Aquinas knew that the poor man was entitled, in a sense, to the apples from the large pile of the soon-to-be rotting Upstate NY Jonamac in his neighbor’s private yard, Locke had an uncharacteristically unhygienic stick up his ass is this regard and held to a much stricter notion of “private” property that would just as soon see the poor man starve.

A pure socialist or communist, you might say, is constitutionally incapable of seeing the skin for the fleas. And a stickler for private property cannot see the fleas for the skin.

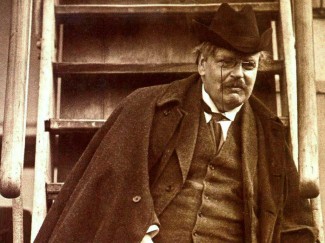

Chesterton, in this regard and in many others, (including body mass), might be seen as the reincarnation of Aquinas. He saw the value of the commons and front porches and even, presumably, the front porch on his own skin: “Man does not live by soap alone; and hygiene, or even health, is not much good unless you can take a healthy view of it or, better still, feel a healthy indifference to it.”

________________________________________________________________

1. “Poets have mysteriously silent on the subject of cheese”–G. K. Chesterton, “Cheese”.

2. “People called commons that part of the environment which lay beyond their own thresholds and outside of their own possessions, to which, however, they had recognized claims of usage, not to produce commodities but to provide for the subsistence of their households. The customary law which humanized the environment by establishing the commons was usually unwritten. It was unwritten law not only because people did not care to write it down, but because what it protected was a reality much too complex to fit into paragraphs” Illich, “Silence is a Commons” (1982)

3. John Locke in Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693) proposed a hardening hygiene for children of cold water, cold air, and light clothing to toughen the body and spirit.

—

Michael J. Sauter is father of four teens and pastoral administrator of his local Catholic parish, St. Luke the Evangelist, in rural Upstate New York.

Please, sir, I want some more.

This was hilarious.

Thank you for confirming me in conservatism forever, and for clearing us all from the insinuation of a too-strict adherence to soap.

One of the things which has changed in the South, particularly in Louisiana, is the radical separation, the Lockean separation between private property and the commons, the latter not to be confused with state-owned property.

It was simply this: boys, feral pigs and wild cows as well as the dogs who helped boys hunt and herd, had an open commons over which to play, to hunt and to work the livestock.

If privately owned property were not official posted, i.e. so advertized in the newspaper for a certain number of days, fenced and arrayed with “posted” signs, then boys, hogs, cows and dogs could freely move on that unposted property. One could pick wild flowers; one could forage for dew berries, huckleberries, black berries, mayhaws, drift wood and even fire wood if trees were fallen. One could fish from every creek bank. One could mark one’s hogs in the spring and round them up for market in the fall. Instinctively, at play, while fishing or hunting or working the livestock, one avoided the homestead of a man and the adjacent, usually fenced land.

This has all changed. Now, everything is Lockean. All of the land which I could traverse as a boy is now off limits to me, including the creek banks. If I step of the highway right of way to pick a violet for my mother, I am trespassing and likely stealing.

Once, here in the South, a mere generation ago, the ladies of the house had an etiquette for greeting unanticipated strangers at the door. On the one hand, a stranger could be dangerous to the household; on the other, one was supposed to be generous and show charity to the stranger. So, as the lady went to the door and met the stranger, there were words, gestures, and intonations which on the one hand kept the world, the commons, at bay, but on the other invited the quickly vetted stranger into the hospitality of the home. This skill, this craft, this breeding is now lost, likely forever; of course, save as a meaningless facade bereft of its previous social function, the front porch, which was where the commons met the private, has disappeared.

The reality is that the Hobbesian state has subsumed the “public” and the “commons.” Outside the ever shrinking private sphere is only the state.

Marx understood the corporation to be a stalking horse for the state, for the corporation gives the illusion of ownership, i.e. legal ownership; but effective ownership actually rests with certain members of the board and with the senior management. So it is with the state: “we the people” have the illusion of ownership; but the factions of the parties and the elites behind them have the effective ownership.

Thus, is the classical since, there exists no commons, save perhaps in the microcosm of the fleas and mites.

Question for you, Mike – do you think that hygiene and fear of disease is the main reason that a lot of churches are skipping on the 2nd and equally important part of communion? The last 3 masses I’ve been to, all in Binghamton in various churches, had only body and no blood! So strange to me, since one of the last homilies I remember at Blessed Sacrament had to do with the importance of BOTH. I hope this doesn’t mean we’ll trend towards those individualized pass-around beaker-sized vials of the wine…

Darn that swine flu!

Dr. Peters,

I am working on a paper about Wordsworth, Cobbett (and possibly other Romantic poets) and the commons. The loss of the commons seems to play a large role in the literature of the period.

Do you have any book suggestions that would illuminate the historical and political reality of the commons? For example, you point out that the commons are different thing entirely from state-owned property. Anywhere I could find trustworthy information on this kind of point would be most useful.

While I am focusing on England, anything you could point to in the American South might be helpful as well. Thanks.

Bedbugs are making a come back, mites have never left us, and you can find spiders, maybe ants or even roaches in most houses– plus mosquitos outdoors in the summer. And anyone with outdoor-visiting pets makes the occasional acquaintance of fleas.

Mr. Cooney,

Some years ago, I co-taught a course entitled Science, Technology and Society (STS) when those courses were the “in thing” in some high schools and colleges. Were I to look into the boxes of notes and books stored some twenty years, I would likely find something, likely, however, dated.

For formal academic purposes, there are likely scholars who write on these fora who could make excellent suggestions as to books and materials, indeed, far better than could I.

My experience with the commons is just that: experience as a Southern boy and as a resident of the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Although the state had encroached on the commons in Germany, there were still many non-state manifestations of it. In the fall, my children and I would take a red wagon and ramble over hills and attendant valleys well aware of and exploiting the rules of the commons. One could pick up any apple in any apple orchard; one could not, however, cause an apple to fall. After the potato rows had been opened and the potatoes harvested, one could, just like Ruth gleaning in the fields, pick up potatoes. One could camp almost anywhere, even build a fire, as long as one respected the property which served as the host. For many Americans, with a more Lockean view the dark side of the tradition of the commons in Germany was that property owners could not do all things with their property. When and how one might cut trees was subject to the traditions of the commons, sometimes ensconced in law. That is likely the topic for another discussion: the limitations imposed by tradition against the limitations imposed by law.

I sometimes write sketches of life in what I call the Commonwealth of Pollock. Therein the reality of the commons, although usually unintended and certainly not poured in from the top, comes to light or peeps through.

Any deer hunt with attendant tales is essentially a story of the commons. An April quest for dew berries in which there was always a snake or two is a narrative of the commons. Who gets what part of a deer, killed ahead of the dogs of another, is a part of the story. What to do with another man’s hog, captured in your herding, is a tradition of the commons.

In the German Romantic tradition, the longing for the commons and the pain of its dissolution can be found across the spectrum of literary genre of the period.

However, for formal guidance to a book or resource, I would turn to the scholars of these fora.

The full text of Illich’s essay on “Hair and the History of the City” is available for reading here: http://backpalm.blogspot.com/2011/09/lice-hair-and-city-space.html

Illich has much more to say about sanitation, dirt, cleanliness, and soap in a book entitled ‘H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness,’ which was written for the Dallas Institute for Humanities that published the book mentioned above, ‘Stirrings of Culture.’ Soap making, it turns out, was one of the first industries to be scorned for its pollution of water.

A fine piece, and especially fine in linking Ivan Illich and G. K. Chesterton. Both men were capable of making connections that never cease to astound us.

Comments are closed.