Thomas Jefferson’s agrarianism has long been vulnerable to attack by unsympathetic critics. Given that Jefferson ultimately banks on virtue rather than folly, this is of course to be expected; but the agrarian part to his vision is also vulnerable on other counts, for it appears to harmonize with a view of “the people” that can be manipulated by demagogues, and it is to some degree founded on a distrust of land merchants who often knew more about Jefferson’s celebrated Virginia backcountry than Jefferson did. By what right, a hostile questioner might reasonably ask, did Jefferson judge Putnam’s and, implicitly, Washington’s knowledge of the trans-Allegheny West? At least those fellows actually visited the country, smelled its ferns, and slept on its ground in the rain.

Nevertheless Jefferson’s agrarian vision has by and large withstood such attacks, and for the simple reason that Jefferson himself was not entirely the figure his enemies imagine him to be.

I don’t mean that Jefferson wasn’t a romantic. On the contrary his romanticism was pronounced. How could it not be, given that his heroes were Locke and Newton? Romanticism and Enlightenment aren’t opposites, they are simply two different mutually reinforcing results of the European turn away from Christian belief, and Jefferson, immensely talented post-Christian man that he was, lived both dimensions to the full. He was a violinist, a classicist, a man of reason in the mold of the French philosòphes who observed nature in much the same way that Captain Cook observed nature, when he charted the lush, exotic islands of the south Pacific. Given Enlightenment credentials like these, it was all but inevitable that Jefferson should also have a strongly romantic disposition, and, indeed, this was the case. “I am but a son of nature, loving what I see and feel without being able to give a reason, nor caring much whether there be one,” he wrote in one letter posted from Aix-en-Provence while sampling olives, cheeses, and wines during a break from ministerial duties in southern France. And fifteen years later, while serving as President of the United States, Jefferson made a point of 1) governing from Washington rather than moneyed New York, 2) riding to work on a horse rather than in a carriage, and 3) never, ever, wearing the sort of wig his peers wore. Clearly, this was a man who was as liberated from “artifice” as he was enlightened by “science.”

Yet—and this is the rub—there was also another side to Jefferson. A lot of what Jefferson wrote came from a stunningly ancient, squarely pre-modern place, and this attribute makes his writings uncannily prescient, in addition to elegant, politically astute, and brave. Witness (besides the Declaration of Independence) the 1798 Kentucky Resolutions. Witness, especially, Jefferson’s statements about “ward republics,” as on view both in letters written between 1813 and 1816, and too in his book, Notes on the State of Virginia, which was written in early 1784, during the same months that he drafted a Congressional report that later served as the blueprint for Northwest Territory development.

Jefferson was a “states’ rights” man, which meant that he favored a roughly equal division of power between the thirteen states, on the one hand, and the federal government, on the other. Thus when the Adams administration successfully pushed for the passage of the 1797 Alien and Sedition Acts, according to which the federal government was granted the right to censor localized opinion, Jefferson cried foul. In this day and age, of course, the original meaning of “states’ rights” has become so entwined with racist associations that it is practically unusable. Nevertheless the original meaning can be recovered, and until someone comes up with a less loaded code name, we will have to make do with asterisks and qualifiers. To Jefferson, at any rate, “states’ rights” meant any right or power not expressly delegated by the Constitution to the federally united states, or denied by the Constitution to the several states, as per the Tenth Amendment, and his point in the Kentucky Resolutions was that the federal government had assumed a kind of “constructive” power that would result in the eventual loss of a particular region’s ability to handle its own affairs and define its own character, within the bounds set by the nation’s first and second charters. “Handle its own affairs” and “define its own character”? How quaint those hopes sound to us now, in this age of massively centralizing, technology-driven forces and a federal government so gargantuan (in relation to the sum total of state governments) that you’d need a scale arm 30 million miles long just to start the balancing action. Nevertheless, widely distributed property ownership was Jefferson’s hope, and even more amazingly he didn’t stop there. On the contrary, he conceived of a way to institutionalize decentralized political power by granting townships and small family farms key, officially sanctioned, ward-like roles in the apparatus of government.

“Lay off every county into small districts of five or six miles square, called hundreds,” Jefferson wrote in Notes on the State of Virginia in 1784. One year later, upon the passage of the 1785 Land Act (with its provision that one section per township should be reserved for educational purposes), that idea became law, and thirty years later, after the legislative, executive and judicial branches of the federal government had all grown in power relative to more localized government, Jefferson expounded on the political dimension to the section-and-range idea in order to remind himself and others of its importance, should lawmakers seriously want to take remedial action. Writing in 1814 to one Joseph Cabell about the state of Virginia, Jefferson confided that he had “long contemplated a division into hundreds, or wards, as the fundamental measure securing good government,” and two years later, in 1816, while writing to the same correspondent and then others, he provided details. “Let the national government be entrusted with the defense of the nation and its foreign and federal relations; the state governments with the civil rights, laws, police and administration of what concerns the state generally; the counties with the local concerns; and each ward directs the interests within itself.” What would those interests be, exactly? Writing to fellow Virginian Sam Kercheval, Jefferson explained that township-directed interests ideally included choosing, installing, and supporting an entire array of services currently under the direction of more distant authorities—to wit, justices, constables, a military company schools for educating the young, a patrol, road maintenance crews, and care for the sick and the poor. In short, townships ought (in Jefferson’s estimation) to function as mini-republics. “It is by dividing and subdividing… republics from the great national one down through all its subordinations, until it ends in the administration of every man’s farm by himself…that all will be done for the best,” Jefferson explained. The key? “Distributing to everyone exactly the function he is competent to” and “placing under every one what his own eye may superintend.” That way, each citizen becomes “an acting member of the government” rather than just a voter who shuffles representatives in and out of office, and the nation as a whole becomes practically invulnerable to attack—both from without and from within.

It was a bold move, to think of dispersing power to such a degree, and it resonated well with ideas crafted long before the Age of Enlightenment. There was, first of all, a Greek aspect to Jefferson’s plan for a grid of small, independently owned farms. Pre-Athenian, polis-based Greece featured a pattern of small, equally sized and therefore equally influential land parcels (read “sections”) which were owned (and defended) by the same yeoman farmers who tended the figs, leeks, olives, and grapes growing on them, and when new land was appropriated by polis-era Greeks (claimed from wilderness-status) it tended to be divided up into small, eleven-acre rectangles in such a way as to form a grid, thereby reinforcing egalitarianism to the same degree that Jefferson’s grid eventually did. Secondly, Jefferson’s thought about a “gradation of responsibilities” strikingly anticipates the deeply rooted and therefore time-honored Catholic principle of subsidiarity, according to which ownership (and therefore responsibility) is ideally distributed to the maximum possible extent, in order to assure the integrity of the social fabric. Jefferson himself, of course, preferred to think simply in Anglo-Saxon terms. Witness his fondness for the term, “hundred,” as a label for the amount of land comprised by the townships he planned, while serving as Virginia’s delegate to Congress. In pre-Norman, which is to say pre-baronial England, a “hundred” was the primary jurisdictional division. It was a German import meaning “100 households,” and though this unit of measurement derived mainly from qualitative considerations like agricultural production and military strength and self-sufficiency, there was also a quantitative aspect, for hundreds permitted subdivision. In densely populated regions, for example, there were “half-hundreds,’ “tithings” (10 households), and “hides” (enough land to support one family and no others). There were other Anglo-Saxon terms for land—one thinks right away of “hurst” (wooded hill), “den” (pasture), “worth” (homestead), and “burn” (stream)—but Jefferson was intrigued mainly by “hides” and “hundreds,” for he was intrigued by the way an Anglo-Saxon “hundred” punned with a square measuring 10 km by 10 km, and he had his eye on the political liberty that could accrue, should property be widely distributed and local institutions prosper as much as they evidently had in England, when lands were surveyed for the Domesday book in 1086.

The problem with Jefferson’s plan for ward republics—and this problem looms now as an almost tragic flaw given that plan’s increasing relevance—was that he tied his agrarian principle to a system of ownership that undercut and ran counter to the world he was trying to create.

Have you ever looked out the window of a jet cruising at 35,000 feet above, say, the Texas panhandle, and noticed the pattern made by pivot irrigation systems that are used to grow alfalfa? The ground, at that point in a transcontinental flight, looks like a board game consisting of precisely contiguous squares, each of them featuring a circle or semi-circle that perfectly grazes each of the square’s sides. One half hour later you fly over Albuquerque, and this time you notice that the pattern formed by major streets and even bulldozed tracks on the desert floor outside city limits seem to be cut from the same pattern that determined the placement of wells at the center of pivot irrigation systems. Can this sort of regularity just be coincidence? To an airborne traveler whose eyes have been opened, patterns on the ground in the Midwest, the deep South, and the far West seem almost to indicate the existence in this country of some sort of ideal or immaculate rectilinear grid that governs the placement of nearly every road, city block, and agricultural field outside of Kentucky, Tennessee, and the coastal Atlantic states. Well, that is exactly what we have. Thanks in large part to Jefferson’s successful advocacy for section-and-range technology we Americans are oriented to a grid that organizes our built landscape so effectively that it winds up organizing, as well, the ways in which we identify, sell, tax, and even imagine real estate.

If you walk into a recorder’s office in Illinois tomorrow and ask for the location of a certain tract, all you need to know are its section, range, and township numbers, relative to the ruling meridian and baseline axes in that geographical region. You say “southwest quarter of section 10, fifth range east of the 3rd principal meridian, 4th township north of the baseline” and you’re done. That might sound complicated, but if you break the code you see that it is in fact simple, and in the days before computers the power conferred by that simplicity seemed miraculous. Ask a homesteader who staked a claim in Nebraska in the 1850s. Thanks to the reliability of the Public Land Survey System instituted by the 1785 Land Act, Nebraskan farmers who staked a claim in advance of a survey team tended to be right, when they spotted the probable locations of section lines, and hence they were able to shop around, as it were, for the instantly sellable “quarter section” that would best fit their needs. But the chief advantage of the Public Land Survey System was not so much that it enabled people to anticipate the future and so get a jump on other, less ambitious competitors. Rather, it was that it enabled a person to act decisively as a seller and a buyer. Thanks to section-and-range logic, western Americans knew what they were buying when they bought a given piece of land, and therefore sales could happen swiftly, without fear. That’s what the Whiskey Rebels learned, when they put down roots in eastern Ohio after fleeing Washington’s Watermelon Army, and given that the survey “machine” making section lines possible roughly kept pace with the development it facilitated, pioneers who came after were able to confirm those rebels’ surprising experience, again and again and again.

One of Jefferson’s primary objectives, in pushing for section-and-range logic, had been to reduce land-sale fraud, and when Congress went ahead and abandoned the metes-and-bounds system with its quit-rents, that objective was in large part realized. At the same time, the adoption of fee-simple ownership made it possible for small farmers to buy land as effectively as land speculators, and consequently a relatively large portion of farmers west of Tennessee and Kentucky wound up owning land. (In the southern Appalachians, where section-and-range technology was absent, almost 75% of the land was sharecropped.) Moreover, Lincoln’s 1862 Homestead Act, which enabled small farmers with zero capital to stake a Lockean claim on a quarter section, depended heavily on the survey system designed in accordance with Jefferson’s vision. However, the abandonment of the metes-and-bounds system also came at a cost, for that turn made possible the commodification of land at the same time that it reduced fraud and facilitated widely distributed ownership. Owing to a reliance on universally applicable, unvarying units of measurement, standardized parcel shapes, and fee-simple ownership, section-and-range logic was the perfect vehicle for conceiving and then treating land as a commodity, and therefore when the system became law it introduced into the mind of the farmer a kind of alienation or abstraction that was not unlike absentee ownership in that it facilitated a use-and-discard attitude toward land rather than a custodial one. Worse yet, the institution of section-and-range logic neatly undercut even the possibility of townships that functioned like Anglo-Saxon “hundreds,” for fee-simple ownership was by definition anti-feudal.

The distinctly, even dedicatedly anti-feudal character to fee-simple ownership is apparent in two ways. First, it involves the replacement of feudal notions of worth with modern ones. When people surveyed land and assessed its worth, in the medieval era, their units of measurement were labor, yield, and quality, not meters or grams. A land’s worth was the number of people, animals, and crops it could support, and you calculated that worth by determining whether it consisted of meadow, wasteland, or ploughland, if it was open, and whether it produced fence posts, firewood, or masts, if it was wooded. In order to make a sale you of course had to use a measuring device that recorded volume or area or physical weight, but that device was typically altered to account for differences in quality. Scale weights were adjusted, paces lengthened or shrank, and bushels grew larger or smaller, depending on what was being sold. Well, the introduction of modern methods of ensuring fairness upended all that. After the switch to constant and universally applicable measures like “pint” and “section”, quality started getting defined on the basis of a varying price, and as a result it became 1) easier to agree on who was cheating who, and 2) harder to think in terms of fertility and the long-term common good, in addition to personal gain. So, that is one way in which fee-simple ownership is inherently anti-feudal. The other distinctly modern aspect to fee-simple land ownership is the way it disables feudal notions of obligations relating to land occupancy. Just as peasants and nobles both had rights to use a given piece of property (nobody flat-out owned land, in the modern sense), so too they both were obligated to respect each other’s rights, in respect to that property, and that meant using property in such a way that the property would still be there, in relatively good working order, for other users’ purposes. Property, in short, meant “fief,” or mini-kingdom. By living on it, everyone paid “fealty” to the common good that this fief, in effect, was. Needless to say, this made ownership in the modern sense complicated. It was as though every piece of property had an endless series of conservation or agricultural easements attached to it, and this made buying and selling difficult. Hence the gradual appearance, in the late Middle Ages, of legal instruments called “quit-rents” which enabled aspiring landowners to buy their way out of encumbrances like medieval easements. The wave of the future was “de-fealtization,” and when the option of literally fee-simple land ownership came along as a way to avoid even quit-rents—see, especially, the 1785 shift from metes-and-bounds logic to section-and-range logic—that dismantling of medieval convention was complete. Starting in 1785, it was possible for land ownership to have zero obligations attached to it. The land was yours to use as you, the purchaser, saw fit.

In other words, Jefferson’s plan for the re-creation of “hundreds” was doomed from the moment he set down his pen. The plan was couched in Enlightenment terms that undermined the Anglo-Saxon vision he was trying to uphold, and therefore his project was, in effect, destined to fail.

Ought we to be surprised?

Not at all.

We are the rattlesnake nation, the nation that says don’t-tread-on-me. Defiance is written into our genetic code, and that particular stance—indeed, the very word itself—means “de-fealtization.” Look it up. To defy is to “throw down the glove,” or release from fealty.

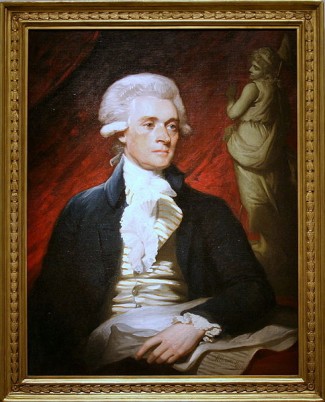

Oil on canvas painting of Thomas Jefferson by Mather Brown

Re: until someone comes up with a less loaded code name, we will have to make do with asterisks and qualifiers.

Um, “federalism”?

“States Rights” is hokey anyway, and would be even in guys in bed sheets had not made it their mantra. States do NOT have rights, neither under Constitution, nor in first principles. Citizens have rights, governments have delegated powers.

Groups and the governments that represent them can have rights as well as duties.

Very interesting discussion. Do you have suggestions for further reading with regard to the history that undergirds your discussion about land, fiefs, fealty, etc.

FWIW, I am not a political theorist, but wrt “state’s rights” I believe that citizens are citizens first of the United States, and that various civil-individual rights derive from that, and shouldn’t be subject to arbitrary and capricious treatment that varies by the state in which one resides.

(Note that a discussion of some recapture of “fief” responsibilities in land ownership through zoning is discussed in the book _Planning the Capitalist City_ and what the author calls the “Property contradiction” and the “Democracy contradiction.” A land owner wants to do what he wants with his property, but injudicious action by others can reduce the value of his own property. So state action–zoning and building regulation–is required. At the same time, this brings public scrutiny and involvement in what previously were private decisions, which they don’t want.)

Historically, citizens were citizens of the states first. Sovereignty lay with the states, not with the federal union.

No, sovereignty was shared (hence “federalism”). Only the federal government could conclude treaties or declare war, for example.

Richard — you asked, a couple comments back, for suggestions regarding further reading. In addition to not-yet-discredited, still enormously helpful mid-20th century works like Henri Pirenne’s Economic and Social History of Medieval Europe and Marc Bloch’s Feudal Society, Vols. I & II, there is a relatively recent book by Witold Kula called Measures and Men, which is a history of the shift from medieval to modern ways of measuring. As for studies that discuss the significance of the 1785 Land Act in these wider sorts of contexts, I would recommend Andro Linklater’s very fine Measuring America (Penguin, 2003). Linklater’s subtitle reads as follows: “How the United States Was Shaped by the Greatest Land Sale in History”.

“sovereignty was shared (hence “federalism”). Only the federal government could conclude treaties or declare war, for example.”

The states were states before there was a federal government. That’s why they were called states.

Individual persons do not have any more rights than do individual bees, individual ants or individual wolves; persons, like their fellow creatures are born into a net or a web of relationships and commensurate responsibilities. Persons, in this context, do indeed have duties, responsibilities and obligations to God, to family, to Church and to the commonwealths and associations of kith and kin.

Sovereignty rests with God alone. No person, no state and no nation is in the order of being “sovereign.” They do hold a certain authority in stewardship, but authority held in stewardship is not sovereignty.

The general government of these states united was created by the states through the instrument of the Constitution which itself is a creature of the states. The creature can never be superior to the creator, even when the creator is written with a small “c.”

In the vernacular of the 18th century, a state was considered, this consideration having been established with the Treaty of Westphalia, a “sovereign.” Sovereigns sent delegates to a congress. Sovereigns did not send delegates to a parliament; hence, our Congress was and should be a gathering of sovereigns, i.e. the states.

At state in the 18th century American sense was not the government thereof – the executive, legislative and judiciary or the bureaucracy – that was the government or polity of the state. The state was the customs, habits, traditions and customs of a people with a unique history on a given territory. The people as mere individuals or in the aggregate were not sovereign. Their sovereign voice at it related to governance was when delegates met in convention to consider such matters as a state constitution, a federal constitution or accession or secession.

There is absolutely no reason why a given state could not go into convention for the purpose of considering the division of itself into ward republics. Now, for a given state that may or may not be a good idea, depending on the circumstances. But it could be done, save for the fact that the general government of the United States has since 1865 become a Hobbesian state, an abstract corporation with a monopoly on coercion and with the ability to define the limits of its own power.

If we can ever emancipate ourselves from the Enlightenment with Rousseau’s autonomous individual, with Locke’s abstract rights, and Hobbes abstract corporation, we might begin to think more clearly about these issues. I have spent twenty-years emancipating myself from them; but the little demons keep popping up in my own understandings, like some many tares in the good wheat.

Mr. Hoyt, you covered the problems in the legal culture regarding land apportionment and ownership, and how it affected the development of states (and communities) at an early time. Would you agree though that the impact of this legal understanding on the development of true communities was rather slight, at least at the beginning, and did not cause problems until later when certain people and groups were able to acquire more property simply because of wealth?

Re: The states were states before there was a federal government.

No, the states were colonies of Great Britain, and as such did not possess sovereignty at all. Hence that little business called The American Revolution. And when they entered into a compact to rebel against Great Britain they ceded some of their putative sovereignty to the federal government they were creating. The Constitution which replaced the original jury-rigged arrangement spells this out in greater detail, and very explicitly establishes that the federal government is supreme over the states, though the states retain some reserved powers.

JonF,

You give the version of the narrative nurtured by Hamilton, Marshall, Story, and Lincoln, the version which has become “the” narrative of the consolidated and centralized state which Lincoln created in the crucible of war. The facts of the time refute the Lincoln narrative in legions of details. I look forward to iron sharpening iron as we discuss this important matter.

“The Constitution which replaced the original jury-rigged arrangement spells this out in greater detail, and very explicitly establishes that the federal government is supreme over the states, though the states retain some reserved powers.”

How does the whole antedate and create the parts which constitute it?

pb — Sorry for the delay in responding. I hit the deck a couple days ago when I heard iron sharpening iron, but seeing as how there’s a kind of quiet I’ll just say that section-and-range technology undoubtedly helped to ensure a wide distribution of land ownership, in this country, relative to overall popualtion numbers. The problem is that the technology also served as a vehicle for commodifying our most significant outward sign of communitarian life, and disentangling land ownership from obligations to serve the common good.

Mr. Hoyt, what do you think then of the claim that “liberal” understandings of property/property rights had more of an impact on the political and social development of the United States than the supposed liberal basis of Constitution (or the Declaration of Independence).

Mr. Hoyt,

Proverbs 27:17 “Iron sharpeneth iron; so a man sharpeneth the countenance of his friend.”

No need to hit the deck. Just a friendly word from Holy Writ and meant in that context when it was penned in paraphrase.

Your point on section-range technology makes a point.

Touche.

“Historically, citizens were citizens of the states first. Sovereignty lay with the states, not with the federal union.”

pb, please read The Federalist Papers sometime. One purpose of entering into a constitutional compact creating a federal government and delegating to it certain enumerated and implied powers, was that, unlike the old Confederation, the federal government should act upon, and be acted upon by, the individual citizenry among the several states. The states would retain powers not delegated, but would no longer by the intermediary between the federal government and the citizenry.

It is also true that before the states became sovereign states, they were the subject and dependent colonies of the British Empire. They became sovereign states only by virtue of their common and united effort. Without federal unity, they might well have lost many attributes of sovereignty, becoming the playthings of competing empires, as the elective Polish crown became the object of the bribes of more powerful European neighbors.

Finally, the Fourteenth Amendment definitively established that the citizens of each state are Citizens of the United States. A constitutional amendment is by definition constitutional. Even states may not deny the liberties of citizens of the United States. It is quite as possible for a state government to become tyrannical as a federal government.

The Federalist Papers are not the tool for understanding the Constitution, unlike the ratification conventions.

Well, the rise of the Home Owners Association has certainly brought back feudalism to America’s suburbs. And cities are beginning to act like HOAs, and people are starting to think of themselves as having a property right in the zoning plan of the city. Feudalism is back!

Comments are closed.