One may notice in this election cycle a certain amount of talk about statesmanship – primarily because each of the candidates is thought to lack it. The latest issue of the Economist refers to “unstatesmanlike” remarks made by Romney. Cornel West says of his “dear brother” President Obama: “I thought that he was going to be a statesman like Lincoln and Roosevelt. It turns out he’s a politician like Bill Clinton.” I choose these examples not in deference to their acumen, but because in each case the judgment comes from a source one expects to be in fundamental sympathy with the candidate criticized.

Both criticisms imply that we measure a presidential candidate against an implicit standard of statesmanship, and we all know that this is something greater than a politician. In other words, when we speak of someone as a statesman, or as failing to be a statesman, we already associate with the meaning of the word “statesman” the possession of certain excellences, or in other words, virtues. Statesman is not a job description; using it implies recognition that someone has the character and understanding to exercise certain virtues in political affairs.

So what then are the virtues of a statesman? On questions of virtue, especially in political life, it’s generally wise to start from consideration of Aristotle’s Ethics.

If we look to the virtues Aristotle discusses, we find that they are not all equal. Three of the virtues in particular are presented as comprehensive, involving possession of all the other virtues. They are greatness of soul, practical wisdom, and justice. Greatness of soul means judging rightly that you are capable of doing great things and worthy of the greatest responsibilities, which can only be the case if you have complete virtue. Practical wisdom requires having the virtues that enable you to desire the right end in every kind of decision and choice, in addition to the understanding of how best to attain those ends not only for yourself but for a community for which you exercise responsibilities. Aristotle describes justice as complete moral virtue in our dealings with others. If we look at the great statesmen throughout history, we find that most of them are especially noteworthy for at least one of these comprehensive virtues, and the most admirable ones succeed in the rare accomplishment of combining all three.

Again, if we look at the presidential candidates, we can see that they want to be perceived as possessing these virtues. In 2008, Obama’s image of being above partisan bickering seemed to imply a certain greatness of soul; his avowed intention to face up to our real problems and tell Americans difficult truths about the challenges ahead suggested that he would be guided by practical wisdom; and of course he claimed to want to build a better future for all Americans, partly by redressing monstrously extreme income inequities, a claim about justice.

In last week’s debate, Obama asked: Why won’t Romney tell you how he’s going to do what he says he’ll do? The suggestion was that either Romney doesn’t know and so lacks practical wisdom, or he’s afraid to say, because his intentions are unjust. In response to Romney’s attack on Obamacare he remarked: “I’ve become fond of the term Obamacare” – a way of saying, “I’m above feeling insulted by my enemies, and can even see their term of scorn as a monument to my name and my accomplishments,” and thus making a claim to greatness of soul

For his part, Romney tried to show that the president’s choices and priorities have been unwise compared to his own plans. He presented himself as a champion of justice when he argued that deficit and budget reduction is not just an economic question but a moral one of our responsibilities to future generations (possibly the moment in which he most sounded like a true statesman). But greatness of soul is a problematic virtue for Romney, since he’s often accused of plutocratic elitism; he can talk about confidence based on his experience as a governor and a businessman, but it would be dangerous for him to appear to believe in his personal superiority over the average schmoe.

And in this last example we see a typical characteristic of the place of statesmanlike virtues in a democracy. There is a tension in how we look at the possessor of these virtues. We can only respect someone who has them, but we can’t endure the thought of the natural claim to superiority that they imply.

We’re conflicted about practical wisdom. The American people want someone with the practical wisdom to solve national problems. But they also want to live in a fantasy world in which they can have everything they want now and not have to reckon with any future consequences. Anyone wise enough to recognize the impossibility of giving them what they want and honest enough to say so cannot get elected.

We’re conflicted about greatness of soul. The American people want someone with the backbone and self-confidence to act decisively according to what he knows needs to be done, rather than someone blown about in the wind of opinion polls. But they also want someone who will do the will of the people, which is apparently expressed in those same opinion polls. They want someone they can respect, who would therefore have to be better than the average person, but they would be offended by someone who appears to think he’s better than the average person.

We’re conflicted about justice. The American people want someone honest and fair, not corrupted by special interests, someone perfectly ethical in his dealings with others. But they also want to elect the candidate who supports the positions of their party. Aside from the fact that a party is a faction with interests opposed to the interests of the other party, it’s also typically the case that justice, even if it makes you loved by the common people, arouses the envy of other political men, who can’t get the favors or cooperation they expect from you and are made to look petty and self-interested in comparison to you. So a party is already at least partially unjust, and it is also nearly impossible for a just man to become a party leader.

So, on the one hand, in admiring these highest virtues, we’re recognizing a natural standard of human excellence, and a natural requirement for exceptional excellence in a good ruler. But in disliking the possessors of these virtues, we show our democratic prejudices in favor of equality and averageness, our inability to endure claims of superiority and our unwillingness to be ruled by the judgment of another about what’s good for us. We despise our politics because it has no true statesmen, and we love our political system because it prevents statesmen from acting like statesmen.

Though the deck seems to be stacked against the possibility of statesmanship generally in our politics, we usually find that the greatest statesmen arise in the moments of most evident crisis. If we look at some of the more conspicuous examples of statesmen who have achieved the rare feat of combining the three highest virtues, they all fit this case. Fabius Maximus defended Rome from Hannibal, and made himself a model for men like Cato. Phocion judiciously steered a much-declined Athens through the troubling times of the growing power of Philip of Macedon. One thinks also of Churchill, and in America such figures as Washington, Adams, Madison and Lincoln. The evident crisis rallied the polity around the necessary men.

It is increasingly clear that we are wading deeper into crisis. If that crisis – being financial and systemic rather than an outright security crisis – could be effectively addressed in any way from the nation’s capitol, four years ago seemed the opportune moment. Obama was not particularly dependent on or beholden to his wretched party, and seemed ready to adopt some more sensible and practical positions than he would otherwise have to. He gave sufficiently suggestive impressions (and had a slender enough record to give few counter-impressions) that he might possess the necessary virtues to excuse Cornel West’s wishful thinking. The race issue worked in his favor not only to turn out voters, but to give him license to exercise such virtues as a statesman: his election was such a historic feel-good victory for American democracy that he might be forgiven for turning out to be actually great and acting accordingly. But he wasn’t that man; pace West, he has not even been nearly a Clinton-level politician.

To be sure, much of the disappointment with Obama has come from impossible expectations raised by a campaign whose implicit message was “Project all your political fantasies on this man” – resulting in possibly the most therapeutic election in American history. But some of that deep and just disappointment stems from the inadequacy of the man to a high but natural measure, rendering him unable to rise to the rare opportunity to be the statesman Americans wish for with (at least in part) the better angels of their nature. Perhaps something of real importance might have been done from the center; I leave that for others to debate. It was not done, and the window of opportunity, if there was and still is one, is surely narrowing.

If you expect the writers at the Economist to be in “fundamental sympathy” with Romney (rather than Obama), I think you’re the only one.

I can’t say I’m particularly interested in arguing over the position of the Economist. Anyone who cares can read the 20 page spread in the current issue on the election. I was speaking in a general shorthand primarily about tax and regulatory policies and the size of government, on all of which they favor the principles that seem to guide Romney’s ill-defined plans. They are duly critical of his lack of detail, unrealistic prognostications, etc. Obviously on social issues they would favor Obama’s moral libertarianism; but then Mitt is one of the least moralistic Republican presidential candidates in a good while.

To be “therapeutic”, the election of President Obama would have had to have resulted in bonafide improvement to the health of the Republic. At this juncture, it can only be deemed, at best, a placebo, at worst, an application of leeches.

Whatever the case may be, do not count upon either party providing any form of Statesmanship. Washington D.C. is entirely too mercenary for that now. It is a new Barbary State. Unfortunately, it preys, unlike most prudent pirates, upon its very own.

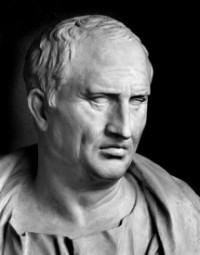

I think the larger problem with Obama is that he articulated in his campaign a relatively cautious approach to health care reform which would have reduced the public/private collusion, and articulated a position of scaling back the intrusiveness of government on private individuals and families in the war on terror, but once elected reversed course, invested significant political capital in a servile state plan of health care reform, and then expanded those same intrusions through executive means. He has been a statesman perhaps worthy of many of the things that Cicero said about Mark Antony (aside, of course, from Cicero’s tirade against Mark Antony’s imprudent relationship with another man).

Comments are closed.