A perennial question in this season: which version of Dickens’ Christmas Carol to watch?

Somehow I can’t seem to muster much interest in any of them but one. After viewing the 1951 version with Alastair Sim, I have never wanted to sully my imagination with any other attempts.

Part of my admiration for this version lies in the extraordinary way Sim first establishes the harsh, almost badgering personality of Scrooge, then gradually undermines and transforms it with moods of fear, defiance, and despair before reaching a final exalted state. Given Dickens’ dubious feelings about enthusiastic Christianity, Scrooge’s progression in the book could be seen as a kind of parody of a conversion, subtracting the truly supernatural and substituting a group of spirits from the Ethical Society.

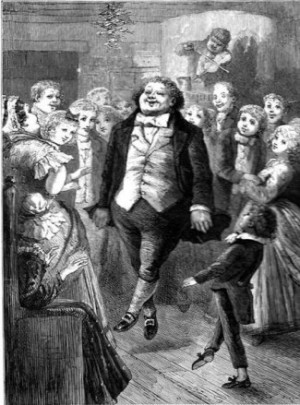

Yet Sim makes the episodes of the nightmare and his resulting change of heart quite convincing due to his bravura performance. I think he succeeds because his acting captures what Chesterton calls the beauty and the real blessing of the story—not the repentance of Scrooge, but “the great furnace of real happiness that glows through Scrooge and everything round him; that great furnace, the heart of Dickens.” Upon awakening to realize his life has been spared, Sim’s Scrooge simply goes out of his head with joy, leaving all he encounters stunned at his newfound and wonderfully ridiculous bonhomie. It’s amusing to see how a kind of spiritual inebriation comes over him.

I recently realized a striking difference between the story and this film version. The role of Mr. Fezziwig has been expanded by the addition of several scenes depicting the fate of his firm at the hands of a Mr. Jorkin (a character invented for the film) who represents, so help me, the Bain Capital way of doing business. “Control the cash box and you control the world,” Jorkin sententiously counsels the young Scrooge.

Jorkin urges the old-fashioned and benevolent Mr. Fezziwig to sell his business: “It’s the age of the machine, the factory and the vested interest.” The latter resists, arguing, “It’s not just for money alone that one spends a lifetime building up a business, Mr. Jorkin. It’s to preserve a way of life that one knew and loved.” In the end, Fezziwig relents and Scrooge goes to work for Jorkin, where his new associate is one Jacob Morley, a chap on a similar path toward those vested interests.

The Christmas Spirit who calls up the wonderful scene of Fezziwig’s Christmas party remarks provocatively to Scrooge: “A small matter…to make these silly folks so full of gratitude,” adding that the party cost no more than three or four pounds. “Is that so much that he deserves this praise?”On my reading, Scrooge’s reply (this scene is in the book as well as the film) contains the seeds of a “servant leadership” approach to managing employees:

“It isn’t that, Spirit. He has the power to render us happy or unhappy; to make our service light or burdensome; a pleasure or a toil. Say that his power lies in words and looks; in things so slight and insignificant that it is impossible to count ‘em up: what then? The happiness he gives is quite as great as if it cost a fortune.”

Unlike Dickens’ story, the film gives us a final exit for Fezziwig as we see him watching in pained resignation from a distance while the sign bearing his name finally comes down to make way for Mr. Jorkin’s new one. The younger (and as yet unreconstructed) Scrooge spies him and hesitates, as though deciding whether to greet his former benefactor. He then turns and enters his new offices without acknowledging Fezziwig.

I would argue that we have here a rare case of the film improving upon the book. As to whether or not the Christmas visions would or would not convert Scrooge, Chesterton remarked, they convert us, as “they were evoked by that truly exalted order of angels who are correctly called High Spirits.” In that same merry mood, Merry Christmas, all.

Hands down, I’d say the best movie version was the one TNT did in 1999 or so. It followed Dickens’s original plot meticulously, for the most part, and it did a realistic background on London during the relevant period, including the songs sung by the Cratchit children.

The reference above to Jorkin is interesting. The Milwaukee Rep stage production has something similar, except it is one Jacob Marley who tried to buy out Fezziwig, and then offers Ebenezer Scrooge his card. But, Milwaukee Rep’s stage presentation of the break up of young Scrooge and his fiancee is strained and bitter, whereas, once again, TNT’s movie version really covers it in subtle and moving realism, as something slips away from young Scrooge rather than being banally thrown away.

Thank you, Mr. Crim. This site–like most concerned with cultural phenomena–needs more such perspicacious and enthusiastic commentary on movies–or novels, plays, even TV shows, I suppose (never watch the latter–I’d rather eat worms), for that matter. Current affairs are, alas, current, while works of art (bad as well as good, alas) are relatively permanent.

I never understood the point of this story; how does Scrooge’s life improve? The Ghost of the Future shows him his gravestone-does this mean that Scrooge is dying because he keeps all his money and that if he starts to give lots of money away, he won’t die? Why are we meant to feel bad that people aren’t around our corpses when we die-do you think we can still hear at that point? Or that you’ll be surrounded by people in a box in the ground?

A great contrarian comment, Fred–practically worthy of Diogenes!

“It is required of every man that the spirit within him should go abroad among his fellow man, and if it goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death.”

Its not about what Scrooge can hear while lying in his grave. It’s about how he lives up to that point, and what he is ready to experience afterward.

“Required of every man” by what? How do you know this? As far as I can tell, this is a mildly interesting story with emotional manipulation.

Fred, I suppose the same could be said of Hamlet, seen from a certain angle. That is, said by those whom the poet Yeats once described as “atheists who whistle in the haunted corridor.”

Comments are closed.