Part III in an ongoing series, Localism and the Universal Church. Read Part I, and Part II.

Berwyn, PA. In the last installment of this series, I contended that an abstract conception of human nature has helped lead modern persons to misjudge themselves and, consequently, to fail to live in conformity with their natures, especially in regard to the concrete conditions of place and community. My argument did not hold up the concrete as an alternative to the abstract, as if embracing the former while rejecting the latter would resolve the lonely drift of mankind. Rather, it proposed that our peculiar abstract understanding is vitiated by a poor grasp of what the abstract actually is. And so, I shall now offer an account of abstraction rightly conceived as I work toward presenting a vision of the Catholic Church as truly universal, and of that universality as vouchsafing the integrity of the particular, the concrete, the local that constitutes human life. How is it, I am trying to discover, that, without betraying the true catholicity of Catholicism, without in any way denying that all men are called to be saved in the Mystical Body of Christ, Hilaire Belloc could dare to say, “The Faith is Europe, and Europe is the Faith . . . The Church is Europe: and Europe is the Church”? To put it another way, why should the Truth itself have had to have taken on flesh? Why was that Truth,which calls everyone, itself — not by chance, or historical contingency, but by interior necessity — brought so quickly to the heart of the Hellenistic world in order to receive articulation?

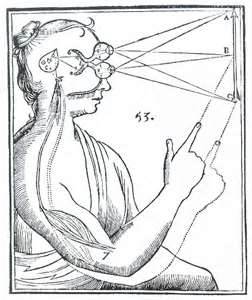

To make a beginning. The abstract and the concrete are not opposites any more than the idea of a cow is the opposite of an actual cow. If they were, then how would one think of a cow? “Well, let us see, if the idea of a cow is opposite to a real cow, then I have only to figure out which animal is also really opposite to a cow . . . yes, of course, a pig . . . and so if I think of the idea of a pig, I shall in fact be thinking of a real cow.” This would surely be to translate a theory of optics into that of intellection and with disastrous results!

An abstraction is simply an idea prescinded from a real being for the purposes of making some aspect of its reality more readily intelligible to our faculty of discursive reason. Although we do not encounter all our ideas in our sense experience of concrete reality, it is only through concrete reality that we do come to encounter and know ideas. Our senses bring us color, sound, and touch, but hidden within them all, far out of range of the senses themselves, is being and the idea of being, and this insensible treasure is the very foundation of reality and of all knowledge.

Although our knowledge rises above the concrete (sense) to enjoy an analytic freedom (to think being), the realization of knowledge in the mind is analogous to the realization of a thing in sense experience: hence, when we truly know something, we not only understand it discursively, we see it with intellectual vision (we see color with the eye, but being with the intellect). So different is the stumbling of the discursive from the simplicity of vision that the one who recognizes this difference readily understands (even if he dissents from) the Platonic tradition of calling all knowledge an act of recollecting some forgotten vision from the plane of eternal ideas. Thus concrete sense experience gives us an analogous standard for our knowledge of the abstract intellective, and cannot be simply dismissed as an inferior shadow.

But there is more. If we come to know all things through our experience of the concrete, we also develop our way of thinking about those things not on our own, and not merely by “mother wit,” some native asocial power of reason. Rather, it is as real rational animals living with other rational animals that we are educated. We depend upon our real communities to implant in us images of the Good long before we can understand them; we rely on them to provide us the paths of reasoning that make thinking well possible; and, because the mind is slow even though, as rational, it is capable of knowing the highest truth, we continuously stand upon the shoulders of our contemporaries and ancestors alike. What we are capable of knowing but could not discover on our own, what we can understand but could not have figured out: such truths constitute the most fragile legacy of mankind; they are lost, and rediscovered, clumsily dismissed and clumsily reconceived.

To dream as Descartes did of a “perfectly planned” city of reason produced by the mind of one individual is to idealize an impossibility, and so to misunderstand the nature of reason. A perfectly planned rational gas station might spring from the mind, maybe. But for all the rest, we must rely with fear and trembling on an inheritance from ages past. As readers of his Discourse on Method will recall, he deprecated the elaborate palaces built on sand, and the crooked streets swelling to vast cities that was the Scholastic tradition of perennial philosophy. But precisely those features that Descartes found most suspect in intellectual traditions—the ongoing debates and disagreements, the sense of deference to past formulations, and the only reluctant innovation for fear of losing the keystone supporting a sublime edifice—are what makes them most compelling and plausible. They signify collective labor and sustained scrutiny; the variability of perceptions when we are straining our intellectual vision toward that light beyond us which we most deeply require; they signify as well an overcoming of the limitations of one lifetime and one mind made possible, on earth, only by cobbling together lives and minds alike across generations. Surely the typical modern person is right that the end of knowledge is the Truth Itself and not any particular expression of it. But if that is the end, it is only in the realm of particular expressions rooted in a shared language and natural community that one may journey toward it. And, finally, it is only in that same language, however homely, that one may finally know it.

This claim is, after its fashion, empirically verifiable. For, experience shows us that it is those who live most comfortably within the inheritance of a tradition and the bounds of a natural community that are the most intellectually ambitious, seeking to know the Truth Itself and settling for nothing less. Such persons prove quite ready to turn from the claims of the body, precisely because the body itself is already well settled. They are more likely to think beyond the immediate concerns of their particular tradition, because their tradition itself has come into being to make possible what transcends it: the contemplation of God. A lack of restlessness makes possible this intellectual ascent, and such intellectual ascent bestows new peace. Perhaps the reader will resent my holding up the old men and women scattered in the pews at daily Mass as the very image of intellectual fulfillment. But I do think they, with bowed heads and gnarled hands clutching a black rosary, are indeed the emblem of what we all seek.

Once one has been alienated from tradition and community, as was to large extent Descartes, one falls back upon the more limited resources of the individual reason and tends to settle for the study of lesser truths—those ready and waiting to be number-crunched by a lonely discursive soul. One may expect to see, in any great “society” of isolated individuals, a myriad toiling away at finite tasks that yield readily testable results that, in turn, can produce material benefits, such as the increase of the individual’s control over his immediate environment or an increase in bodily health. Such rationalistic short term exercises are the natural horizon for those who have lost the inherited resources necessary for the mind to ascend beyond the temporal. And one should expect them to breed results—advances, progress!—for, what else is the intellect enslaved to restlessness to do but be materially productive? If one cannot trust that one’s ideas will find immortality in the mind of a communal tradition, one comes to trust only such ideas as can be reified, locked securely in dead matter.

The Traditionalist rebuke of modernity or the Enlightenment project thus has a great point in its favor. But it too readily seeks to oppose the claims of modernity rather than explaining why modern persons do not really understand themselves. In proposing abstraction as an evil, traditionalists, such as Joseph de Maistre, fail to appreciate that one of the great goods traditions makes possible is the fruitful use of abstract reasoning. In opposing a reductive rationalism, they fail to see that human beings, as rational animals, could hardly remain long convinced of arguments that go against reason. (Hence, they will sometimes seek to define man as a “religious animal” rather than a rational one, without appreciating that he can only be the former when he fulfills his nature as the latter).

But the argument for fidelity to inherited tradition and natural community is consummately rational. For, inherited tradition and natural reason are the conditions of possibility for a properly functioning human reason. That does not absolutely mean human beings may not know the Truth Itself without these things—for the Maker of All Things has other gifts besides these. But for most of us, tradition and community make such knowledge possible and they make it fruitful, for they give us the rational tools, the language, to reflect upon it. The only thoroughly irrational position for the rational animal is to seek to ground all one knows only in what one has discovered unaided and ungifted from beyond oneself. And that, unfortunately, is the modern criterion of rational certitude.

The traditionalists of the Nineteenth Century tended to propose an explicitly slavish conception of human dependency on tradition; this very notion strikes me as evidence that they felt more painfully than they acknowledged the point of Enlightenment critiques of society as artificial and of tradition as imposed. I have suggested, to the contrary, that man as a rational animal is also man the political animal, and that life in community is natural precisely as the condition which makes possible the fulfillment of man’s rationality. This is not to say therefore the human being must be uncritically tradition-bound. Everything one says within a tradition that claims to be true ultimately refers to a truth beyond that tradition. Traditions grow and flourish unevenly as a result of their particular internal genius and in their response to proposed internal criticisms (though the ultimate origin of a criticism may be outside the tradition, the criticism itself would have to be made internally, in the language of the tradition, if it is to become intelligible). Consequently, every particular tradition is better or worse than every other tradition and we can often make compelling if provisional judgments between them.

I should reiterate that Truth’s stand infinitely beyond any particular tradition in no way relativizes traditions in the way the notion of “relative” is typically taken in our day. For a tradition is also effectively absolute insofar as it makes possible the human search for, and the articulation of, the truth. Knowledge of the truth does not relativize a tradition, either, for it is within a tradition that one stands in order to gaze upon truth and, no less importantly, to live in light of it. To instrumentalize the notion of tradition, as if it were a means to arriving at Truth and dispensable once one has arrived there—while a common liberal narrative—is much like saying one only needs ground until one gets to the edge of a cliff, and from there the air will do. For, if tradition is merely relative to the Truth, it is relative as the ground on which a watcher of the sky stands is relative to the planet he observes swim into its ken. Failure to grasp this has led liberal rationalism to dead-end, time and again, in one flabby version or another of atheistic mysticism.

Thus, traditionalists are correct in defending tradition per se as indispensible, but they tend to do so in terms that diminish the function of reason in human life. But to sin against tradition is also to sin against reason. And it is only because we have the capacity to abstract from concrete experience the notion of “tradition” that we can theorize how traditions work and affirm them as indispensible. We can affirm traditions as better or worse because we can judge them by means of abstraction. The only thing we cannot do is stand outside of any tradition if we hope to use our discursive reasoning fruitfully in the tasks of abstraction and judgment.

Here I arrive at a final criticism of most species of traditionalist thought. They tend to accept the modern critique of tradition as valid: traditions writ large are irrational and relative entities constitutive of a particular people’s way of life and thought. Human beings live better when firmly attached to a community and its traditions, they affirm. As such, traditionalists are making blanket, abstract defenses of tradition per se. They do not always defend simply one tradition at the expense of all others, and even when they do, they still affirm the abstraction “tradition” as a per se good, even though this affirmation seems to remain impervious to rational explanation.

If the weakness of traditionalists appears most obviously in this affirmation of tradition as a universal, abstract, but irrational good, so does the typical modern liberal, rationalist position reveal its weakness not in being abstract, but in being inadequately so. It dissolves concrete reality into the dust that will serve as the plaster for the new reality it would make by means of mathematical reasoning, but it seems oblivious to the fact that not mathematics but metaphysics is the most abstract of the sciences. In giving up the concrete, modern rationality loses interest in—or the ability to think—being. And, in surrendering being, it surrenders not so much individual truths subject to our manipulation, but the Being and Truth that stands above and beyond the capacity of the mind to count or the hand to control.

With rationalists, I affirm the necessity of arriving at universal truth by way of abstraction, and with the traditionalists, I affirm tradition as a per se good, and I do not hesitate to do so because I believe human beings per se require a particular natural community and a particular cultural and intellectual tradition in order fully to be themselves as political and rational animals. This is a universal claim—one arrived at by means of abstraction and reason, and one I believe to be binding on all human beings. If it is a true claim, that means it is a universal one as well, whence the force of its binding. The most compelling intellectual tradition will be that which can understand and affirm the function of natural community and inherited tradition without in the process either dissolving or idolizing those things. It will be the tradition that can affirm with confidence the essential role the local and the particular play in all aspects of human life, especially the cultivation of reason, precisely because such things are necessary to a fully rational, a fully human, a truly happy, life.

I hope to show that the Catholic Church contains within itself just such a tradition, and that that Church, because it is not reducible to a tradition, has been the surest means of helping human beings to fulfill their social and rational natures by dwelling in a Mystical Body that transcends all earthly society and exceeds without violating all discursive reason. Finally, I hope to show that this Mystical Body lends to the particular and the concrete, to inherited tradition and natural community, a dignity, indeed a sacral character, toward which natural human pieties incline but cannot of themselves obtain.

Mr. Wilson,

Thank you for this article. We are indeed embodied souls, not ghosts in a machine; however, we are all tempted to sunder ourselves into false dichotomies and to defend the side which we prejudice, thereby diminishing ourselves and estranging ourselves from the Incarnation and the sacramental. Among those tempting dichotomies are tradition and abstraction.

The rational is oftentimes like a Potemkin Facade , tidied up so as to create calm unanimity and order or perhaps awe. Behind the facade however, is the real meat of human existence where we happily wallow like cheerful omnivorous swine in a muddy hole of superstition, dreams, waking occupations and fear. This is why literature seems to favor the back alley, it is more scenic, if a tad prone to various attacks by sundry injuns, real or imagined.

Loved the Descartes bit. A “perfectly planned City of Reason” scares the bejeeesus outa me. All them Homunculus taxi drivers going about their arid business.

But then I have a bad attitude, I’m actually becalmed by Jackson Pollock’s “Convergence 1952”. Their is order and process in this messy abstraction.

Best to you as usual

“This claim is, after its fashion, empirically verifiable. For, experience shows us that it is those who live most comfortably within the inheritance of a tradition and the bounds of a natural community that are the most intellectually ambitious, seeking to know the Truth Itself and settling for nothing less.” While I suspect it is true that those who live within a tradition and in community are more likely to gain a wisdom that will elude the restless rationalist, the empirical verifiability of that claim is, well, unverified. Are those in remote Afghan villages, Roma families in Europe, Arab nomadic tribes, or Chinese villages more intellectually ambitious than contemporary urban cubicle workers? Less distracted and less given to the acedia of modernity, certainly, but that does not make them any more ambitious for truth than those who lack community. In the case of the Catholic Church, the sacraments provide “concrete” or material expressions of truths we otherwise would not see and feel, i.e., abstractions, and as you point out, the bread, wine, water and oil are not the opposites of the truths and grace they bring to us. They transcend particular local communities, and the Church always has to work carefully to maintain the truth of the Gospel and the Magisterium while adapting to local tradition. But that particular tradition has to adapt to the Truth as well.

[…] Part III “Abstraction Rightly Understood“ […]

Comments are closed.