Three articles recently caught my eye, all of which having to do with scholars’ fame, only two having to do with their libraries.

The bookless one involved a professor of history at the University of York who blamed the victims — that is, the students who refused to enroll for his second-year course in medieval history. According to Inside Higher Education:

[Guy Halsall] responded to an underattended second-year lecture by telling students they were failing to make the most of the “obscene amounts of money” that “mummy and daddy” were paying for their education.

For that money, he said, “you get the chance to hear (probably) the most significant historian of early medieval Europe under the age of 60 anywhere in the world give 16 lectures on his current research.” He added that “people pay said lecturer large sums of money and fly him around the world to talk to their students, or to give keynote lectures at conferences.”

Halsall eventually apologized, but likely with his ego well intact.

But what will become of professor Halsall’s library when he leaves this mortal coil? That was not Hamlet’s question but after reading a librarian and book seller on the disposal of scholars’ books, it is one that likely haunts any academic who aspires to some kind of intellectual immortality. Andrew D. Scrimgeour, dean of libraries at Drew University, describes the process of becoming acquainted with the literary remains of a deceased scholar:

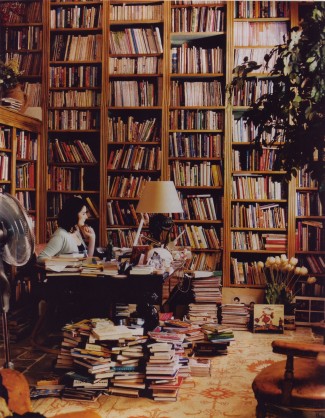

I have been here many times before. Not to this particular library but to others like it. Some have been on college campuses, others in private homes. Some have sprawled through many rooms, including the bathroom; others were confined to a single space. One had no windows; another overlooked a lake. Most were crowded. All were dusty.

Each was the domain of a scholar. Each was the accumulation of a lifetime of intellectual achievement. Each reflected a well-defined precinct of specialization. But what they also had in common was that each of their owners had died. And by declaration of their wills, or by the discernment of their families, I had been called to claim or consider the bereft books for my university library.

Scrimgeour notes that the arrangement of books, personal affects, and images reveals more than a private detective might decipher:

What first catches my eye on this day is the calendar on the desk — a small scenic calendar from Vermont Life. It displays October 2004. (Professor White died on Oct. 31, 2004.) It’s as if time froze in this space on the eve of All Saints’ Day. Two volumes of Calvin’s “Institutes of the Christian Religion” hold pride of place in the middle of the desk — one open and face down, undoubtedly the last book he was reading. Bach’s chorale preludes are in the CD player, and my first act is to fill the library with the music White loved and often played on the spinet piano in the adjacent room. Before disturbing anything, I photograph the room from several angles, ensuring that his desk and books are captured for the archival record. . . .

The placement of individual books, as well as the adjacencies of groups, intrigues me. Are they subject categories, chronological gatherings, project clusters, a map of intellectual terrain or evidence of the constraints of space and shelving? Which books are closest to the desk or kept on the desk? Which are consigned to the bottom and top shelves or the closet? Books sequestered in the shadows behind others suggest clandestine reading and hidden pleasures. Sometimes, though, they are simply gifts hidden away for a coming event — a birthday, graduation or anniversary — a greeting card, yet unsigned, often their companion.

Scrimgeour does not stand back to consider the constraints of mortality or what literary evidence may reveal about a scholar’s failed or frustrated aspirations. He mainly wonders about the effects of electronic publishing on the personal and tactile world of a scholar’s library and the disposition of its titles:

. . . what has taken years to create, I dismantle in a matter of hours or days. All too soon, walls of colorful volumes are reduced to a cube of brown cartons resting on a pallet, without a hint of the academic landscape they once shaped. The room itself becomes stark, the bookcases empty, the sweet autumn musty scent of the older books gone, only photographs, stapler, memorabilia and much dust remaining. . . .

I wonder what the experience of future librarians will be as electronic books increasingly dislodge those that can be touched, smelled and boxed. Will private collections in the digital environment add value to university libraries, or will they be constrained by complex copyright laws? Will they convey a unique ethos, capable of stirring admiration, even sadness and rituals of respect, from the librarians sent to gather them?

For the moment, the collections to which I am called still consist of paper, ink, glue, covers and jackets.

Leave it to a bookseller to talk about the value of a scholar’s library and how fast it diminishes after death, almost as quick as a new car loses value when driven off the lot. Hugh Gilmore, who writes a regular column (“The Enemies of Reading”) for the Chestnut Hill Local and buys and sells rare books, described last month his experience of disposing the library of one of his professors at Temple University. He normally would have made the visit to the academic’s home office simply to see what the family wished and determine the books’ value. But this time when he learned that a professor he had esteemed was the owner of the books he was to inspect, he changed from entrepreneur to intimidated sleuth:

Since the “lit crit” would be, with a very few exceptions, of little commercial value, were any of the literary works first editions and possibly valuable? I began pulling books by famous writers. Evelyn Waugh, Grahame Greene, Henry Green, W.H. Auden, Ronald Searle, P.G. Wodehouse, for example.

If the outer condition (covers and/or dust jackets) was in good shape, I’d open a book to check its edition. It’s an entire other education to know how to do this, but one frequent, simple way is to see if the title page and copyright dates agree. Some publishers make it easy by saying “First printing.” Not many publishers are so obliging though.

Some of the books I pull are firsts. Most are not. Even with the firsts, however, there is a problem: on the first blank page, in a large hand, is an inked notation like this: “Robert Llewellyn, Blackwell’s, April 1951, $2.00.” Every book. An ownership signature, unless the person was famous, knocks the price of a first edition in half. Is this book, therefore, worth carrying down three flights of steps and down the ramp to the van at the curb? Will it sell in today’s market?

I need to take home about four or five boxes of books as samples to research the Internet market values for them. I go down and ask the family. They say yes, I may do that. I re-ascend and fill four boxes with samples of the various kinds of books.

Two hours had passed by then. I have my samples. I’m now looking for rarities – obscure things that elude the casual, untrained eye. But a nagging feeling is slowing me down. A feeling I need to acknowledge.

It was time to deal with the elephant in the room: Where you are, Hugh?

“I’m in my professor’s house.”

“Where in your professor’s house?”

“In his sanctum sanctorum.” His holy of holies.

“Let’s not forget that, Hugh.”

So … yes … I pulled The professor’s chair back from his cluttered desk and sat in it. I got up again. I’d sat on a large Random House Dictionary covered by a thin cushion. Was I really taller than he? He seemed such a god. I sat again.

I thought, I am in Professor Llewellyn’s personal home library. I am now sitting in Professor Llewellyn’s chair. I am facing Professor Llewellyn’s desk. I’ve come here to take Professor Llewellyn’s precious books away from his precious study. I feel like a bad boy.

I don’t know what he thinks of someone like me – I mean “I” – free-ranging among his books. Or what he thinks of me, if he’s looking down from above. Aren’t there laws against having students break into professors’ houses to disturb the order of their private universes?

I’m looking at Professor Llewellyn’s wall calendar and above it, the pictures of famous writers he’d tacked up. This desk is frozen in time, I imagine, since he died five years ago. There are unopened packages of books on the floor.

I am in awe. I feel I have I have no right to be here. I have so much respect for Professor Llewellyn. The last time I saw him I was 22-years-old and fresh from the streets of a blue-collar mill town, Colwyn, where I’d never see the likes of him before. I feel his presence. I feel rude.

Not to be missed in this account is the cold calculation of literary criticism’s value. Gilmore underscored the point in a sequel:

This selfsame topic of literary criticism, at which I tried to excel as a lit major in college, but which bored and confused most students, is of interest to very few people on this planet. People struggle to read fiction at all nowadays and, outside of classroom compulsion, almost never buy criticism, certainly not for reading pleasure. There is very little demand for it.

And with the descent of the library’s value thanks to its books about literature, so came Gilmore’s realization that an inspiring lecture and brilliant professor’s literary possessions have little life beyond the one of their owner:

A library is a one-of-a-kind assemblage, a mirror of its creator’s concerns through the days of his or her life. The most ideal thing one could do would be to pack it up and transport it whole somewhere it would be appreciated. J. Pierpont Morgan and a few others (including, in another medium, Albert C. Barnes) managed that, but they bequeathed genuine rarities.

Most people, including Professor Llewellyn, assemble a combination of reference and pleasure books that is often so personally eccentric it would not fit anyone else’s life. In fact, to push the point a bit: Whoever receives another’s library loses the pleasure of assembling his or her own.

Ah, but Professor Llewellyn’s library was also a professional one, as it turned out. I’d venture that at least 90 percent of the books were either English literature or works analytical of the same. Couldn’t the collection be shipped as a whole to an institution?

From the 1940s through the 1980s that sort of thing did happen.

The famed Philadelphia bookseller George Allen once had an emergent college order his entire catalog of Classic Roman and Greek books. And for a while, new institutions, often foreign, bought large libraries whole. But in this post-Internet world those days seem to be over. Far more often, books move in the other direction as libraries deaccess books to accommodate the incoming flood of electronic databases, e-books and “alternative” media.

Professor Llewellyn’s library would have to be dispersed. The “Big Bang,” as I call it: The books come in one at a time over the years and achieve a certain mass until (to borrow from Yeats) “the center cannot hold,” and they explode back into the world of people who care about books. (My “Big Bang” analogy falls down here since that world is shrinking.)

If the professor had accumulated only literary first editions by important writers, or had built a library of books about the Civil War, or steam engines, or motorcycles, or early American trade catalogs, or 18th century hand-colored floriculture or several other topics that remain hot, the library would be easier to move. But he hadn’t. He’d owned later printings of literature – usually worth much less than a new paperback of the same – and tons (literally) of literary criticism.

Readers can well imagine that if professor Halsall, back at the University of York, is as famous as he says, his library might remain intact and find an academic home where a librarian will devote an entire room to the books that informed such a great man. But the rest of us pikers will face a fate much like Gilmore’s former professor — a collection of books that function for the span of a career but are also limited by the interests and duties of that work. Above all, those books will not be rare enough to do more than provide — at best — a week of dining for an academic’s surviving spouse. T. S. Eliot’s library may still survive, Sharon Elliott — emeritus professor of English literature at Mount Zion University — her library will not. Here’s how Gilmore put it:

Of course, if Professor Bob had accumulated 6,000 volumes of first-edition Hemingways and Faulkners and Dickens and Jane Austens and so on, preferably in fine condition, and signed … I’d have found a way to handle the entire library myself. But he hadn’t, he’d formed a working library that represented a time capsule of literary criticism and history and analysis during the all-too-brief 80-or-so years he lived on earth. The library was a testament to his sparking intellect, deep powers of concentration, willingness to work hard, and sheer love of learning.

If a former student can write that about my books when I am gone, it will show that someone actually took my class, learned something, and valued the instruction. Not a bad way to go even if a few rungs down from where we thought we were heading coming out of graduate school.

Hart, my friend, a writer’s worth is measured by the number of comments he gets, and he gets comments by writing about guns or civil unions or leprechaun girlfriends, not about libraries. Please try again, and this time make it meaningless.

JP, what if I had dropped a few f-bombs?

Well then of course during the winter months the angle of the sun is low; the doors and windows shut and so the dust motes are clearly seen as they drift up from the carpet whenever it happens you are struck by a sentence and look up from the book.

What I thought here “If a former student can write that about my books when I am gone, it will show that someone actually took my class, learned something, and valued the instruction.” was that what this essay is about is in part the quite literal or concrete transmission of culture from one generation to the next.

And I suppose, thinking of the people I looked up to, that, outside of a few volumes, what is being passed down is an expectation that one will build one’s own library, that such a thing has value – the literal, concrete expression of these: ” deep powers of concentration, willingness to work hard, and sheer love of learning.” Not a bad way to go at all.

Or, Peters, might we discuss the fricassee of some free range delectable? Anything for immediate results is best. bourbon always works but I understand that it is in short supply now. Exactly what the hell kind of culture would allow its bourbon supply to range into dangerous territory?

Walsh,

Literacy, when taken to professional levels is deemed an eccentricity by this era, as well as many previous eras. Our hero worship, as Tocqueville observed, revolves around physicality and action. …”everyman considers himself an artist”…or words to that effect while the artistic output diminishes in quality.

Too bad affirmative action does not include the promotion of people who actually like to think…and think against the grain. The Republic once possessed this trait, it has been ground to dust now. Opinion now masquerades as thought, mobbing down the street like a pack of dogs trailing a Garbage Truck.

Sabin,I find that disappointing. Solace this week came in the form of seed catalogs in the mail and, despite the bitter cold lately, unmistakable lengthening of the day. Put another way, I turned everything off and spent some time outside.

Comments are closed.