Rock Island, IL

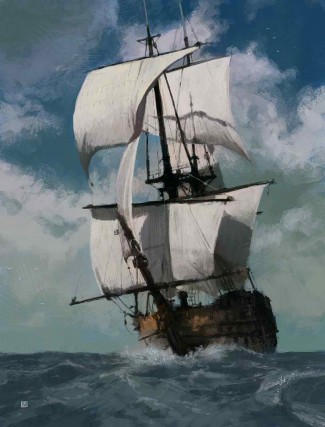

In Letters from Lake Como Romano Guardini asks us to consider a sailing vessel, which, “though it is of considerable weight, the masses of wood and linen, along with the force of the wind, combine so perfectly that it has become light.”

“We have here an ancient legacy of form,” he says. “Do you not see what a remarkable fact of culture is present when human beings become masters of wind and wave by fashioning wood and fitting it together and spanning linen sails?”

But “mastery” as Guardini uses it is not mastery as we usually think of it. He is not interested in the modern project of easing man’s estate and achieving what according to Bacon was truly lost in Eden: complete dominion over nature. Guardini neither flaunts modern credentials nor posits a state of nature such as Locke or Hobbes or Rousseau might recognize: “In nature ‘untouched,’ in the order in which animals live, we have no place.”

Our dwelling place, he says, is the state not of nature but of culture. “The human world is putting natural things and relations in a different sphere, that of what is thought, willed, posited, and created, and always in some way remote from nature—the sphere of the cultural.”

For Guardini, “to be human is to have mind and spirit at work,” and so for him the sailing vessel is infused with mind and spirit. Swimming or frolicking in the breakers may give us a certain “intoxication of kinship with nature,” but we were not made like fish to live in water. We live by artistry, and artistry always implies a remove from “nature ‘untouched'”: “in the finished sailing vessel, a certain distance from nature has already occurred. We have both withdrawn from nature and mastered it. Our relation to it is now cooler and more alien. Only in this way can any work of culture, of mind and spirit, be done.”

But this is no matter for lament.

“Yet do you not see how natural the work remains? The lines and proportions of the ship are still in profound harmony with the pressure of the wind and waves and the vital human measure. Those who control this ship are still very closely related to the wind and waves. They are breast to breast with their force. Eye and hand and whole body brace against them. We have here real culture—elevation above nature, yet decisive nearness to it. We are still in a vital way body, but we are shot through with mind and spirit. We master nature by the power of mind and spirit, but we ourselves remain natural.”

By contrast, says Guardini, the steam ship obliterates the decisive nearness. It is naught but elevation above nature. No one on such a ship is still in a vital way body. “A colossus of this type presses on through the sea regardless of wind and waves. . . . People on board eat and drink and sleep and dance. They live as if in houses and on city streets. Mark you, something decisive has been lost here.”

Guardini offers other examples by way of illustration, among them the mastery of fire in the hearth and the cultivation of the earth by the horse-drawn plow. In both cases there is real culture: mastery of and yet proximity to nature that neither the central furnace nor the tractor manages to retain.

There is no attempt in Letters from Lake Como to fix a line, only to say that with each change, with each “step-by-step development, improvement, and increase in size . . . a fluid line has been crossed that we cannot fix precisely but can only detect when we have long since passed over it—a line on the far side of which living closeness to nature has been lost.”

Let us not miss the point: Guardini is suggesting that mastery of nature need not mean we cannot also have full integration into it.

But at a certain point, somewhere beyond that fluid line, it means exactly that: no integration, only mastery—mastery over rather than mastery of, which is to say the Baconian dream: ocean liners, climate control, and the thirty-two-row air conditioned combine with surround sound and GPS.

The sailing vessel, which Guardini says preserves “an ancient legacy of form” shot through with mind and spirit, “the lines and proportions [of which] are still in profound harmony with the pressure of the wind and waves and the vital human measure”—this vessel, this bark, this thing that has proven to be so richly emblematic (think of Donne’s “A Hymn to Christ, At the Author’s Last Going Into Germany”) merits the attention Guardini gives it as both emblem and artifact. It reminds us that we do in fact have a choice in how much mastery we achieve—and in how much nearness we are willing to surrender. The evidence around us suggests that for too many of us the mastery should be unlimited and the nearness entirely surrendered.

Guardini lived long enough to witness the brute unintelligence of the bulldozer, though not the Eucalyptus Muncher of which I wrote in the early days of FPR. But the truth is that almost all of us—I include myself—are the beneficiaries or victims (take your pick) of such marvels as the table saw, the automatic dishwasher, and the golf cart (that chief of all abominations).

What we are not the beneficiaries of, near as I can tell, is a sustained intelligent discussion of form—form and its bearing on our relation to “nature ‘untouched,'” which the architects of modernity, spurning their Aristotle, assumed to be our default condition.

I don’t hear Letters from Lake Como on very many lips. I don’t see the book on very many syllabi. I don’t hear it discussed among those who ought to care deeply about form: artists and scientists alike.

Here is Wendell Berry on art and science and the problem of form: “Without propriety of scale, and the acceptance of limits which that implies, there can be no form—and here we reunite science and art. We live and prosper by form, which is the power of creatures and artifacts to be made whole within their proper limits. Without formal restraints, power necessarily becomes inordinate and destructive. That is why David Jones wrote in the midst of World War II that ‘man as artist hungers and thirsts after form.’ Inordinate size has of itself the power to exclude much knowledge.”

The thing about artistry—true artistry—is that it is characterized by the limits of form: a sonnet is limited by its rhyme scheme and syllabic count, a piece of music by (among other things) its time and key signatures, a portrait by its frame, a statue by the piece of marble it steps out of, a farm by its conditions and the skill of its husbandman. Not that the disregard for such limits hasn’t manifested itself in poetry, music, sculpture, painting, and farming—or in other arts. In all our arts we can find versions of the steamship.

Guardini’s sailing vessel should help us begin to think again about what Berry calls “propriety of scale.” But we are going to have to know the meanings of such words as “propriety” and “scale.” We would do well to know what “property” and “form” and “art” mean as well. But that will mean wading into the currents of “restraint” and “truth” and “beauty” and “goodness.” And where will that end?

Maybe in an artistry, shot through with mind and spirit, that achieves mastery of while preserving nearness to.

“In nature ‘untouched,’ in the order in which animals live, we have no place.” Burke would appreciate this sentiment. The rest of the article seems to imply the principle of standing athwart history yelling stop. Russell Kirk wrote that “Burke, and the better men among his disciples, knew that change in society is natural, inevitable, and beneficial.” How do we reconcile human scale, as described by Mark Mitchell, with the benefits of economy of scale? Do we shirk our moral obligations to society because we fear the dangers of (or dislike the direction of) progress? Is it not a duty of contemporary society to improve itself and to pass on the benefits to its children? Not just materially, but to also insure their prosperity and well being.

Wonderful essay. This reminds me of a reflection by Coleridge in his notebooks during his Mediterranean voyage where he lauds the unity in diversity between the myriad sails and rigging on a ship and their harmonious function as one body. I was surprised that he gave the ship living, organic qualities versus complaining about its “mechanical” nature.

Mr. Porter: I think the question is what constitutes progress. Economies of scale are all well and good if they are efficient and they produce things conducive to our flourishing. But as Prof. Peters says at some point you know you’ve crossed an invisible line. When a substantial portion of the food we produce is never eaten and goes to waste, when a large amount of time, money, and brain power is consumed trying to design advertising that intentionally manipulates people and manufactures desires, when pornography is used to sell Hardees hamburgers at 3pm while my six-year-old nephew watches, you know something has gone horribly wrong. That is when reflective people should stand athwart history and yell enough.

“Guardini is suggesting that mastery of nature need not mean we cannot also have full integration into it. But at a certain point, somewhere beyond that fluid line, it means exactly that: no integration, only mastery—mastery over rather than mastery of…”

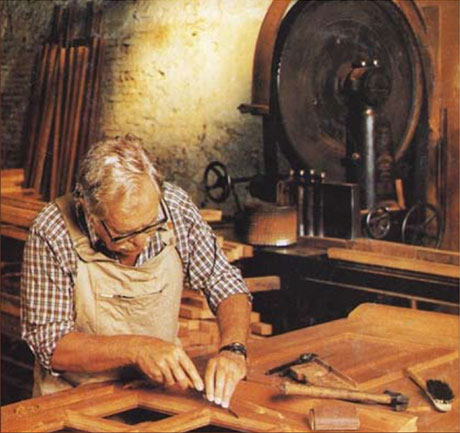

Yes, and that line exists in any craft. In woodworking, the traditional craft I know best (though I’m far from expert), we cross it at the point where our tools allow us to ignore the tree that produced the wood. If a tool permits the worker no longer to be aware of the grain, the species, the way the wood was dried and shrinks and breathes, it has enabled “mastery over” and not “mastery of.” I consent to using power tools for rough work where the benefits of that knowledge would be minimal and I’m better off conserving my energy for more precise tasks — ripping two-inch-thick boards, for example, though even then I’m aware that I’m losing knowledge of the material that might help me later.

Now, true, I’m a hobbyist; I don’t have to do this for a living, and I’m not constrained by the need to produce. The time I spend on that craft is an asset to me, not a cost. One could argue — as Mr. Porter suggests in his comment — that this makes that focus on craft impractical in the “real” world. But one could also argue that we actually need very little of what we think we need, and that what we gain by craft is greater than what we gain by what it produces — and more relevant to our well-being, if not to prosperity, which is something different, I think.

Good to see you back, Jason, if only for one essay!

One of the best arguments I’ve seen for the superiority of a well-designed golf course to nature undefiled.

Thank you, Jason, for this fine post. You (through Guardini) have given me fresh words for understanding the joy I experience when I sail my own boat, and you have sent me back to re-read at Guardini’s “Lake Como”. I hope I get to buy you a Scotch someday in repayment.

Thanks for this, Jason. A friend gave me a copy of the ‘Letters’ a few months back but I haven’t read them yet. I’ll have to remedy that. I also recently scored a copy of ‘End of the Modern World’ which seems to be somewhat scarce, at least at a decent price.

A friend of mine points out: it’s easy for like minds to agree (I do) with this essay and acknowledge that our modern life has overshot any propriety of scale, but that overshoot also may imply (it seems so to me) that 7 billion human souls (for that is what they are) can’t be sustained if we suddenly went back. And slow reversal implies centuries of smaller generations supporting larger aging generations, which comes with its own problems. So what ought be the way back? Seems like there will be vast pain on any path we take, or are forced to take.

@Jon, I wouldn’t be so sure about insisting that mastery over is necessary to feed the world. Lots of good evidence of the vast successes from mastery of in the production of food, however so little we may hear about it. Case in point: http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2013/feb/16/india-rice-farmers-revolution

“Our dwelling place is the state not of nature but of culture.”

True and this seems to be lost on the biological determinists of the Right as well. They claim to derive and establish marriage from sexual complementarity of the male and the female.

But animals do not marry. And how is it even possible to derive marriage vows of fidelity and wifely obedience from sexual complementarity, I can not imagine.

So, the Left is correct, in this at least that sexual complementarity by itself does not imply marriage.

The ancient Greeks didn’t have a word for what we consider today as being Art. They used the word ‘techne’ which meant roughly ‘the skill needed to get the job done.’ This seems to fit the idea behind the term ‘artistry’ used above.

But Modernism brought a different idea about what Art could be. Art didn’t have to be about skill or how perfectly something was made or painted. Art could be about an idea.

This is neither better or worse than the previous idea of what Art was. It’s different.

Happened to be reading Richard Weaver this morning, and he mentions this “mastery over,” referring to it as the “metaphysic of progress through aggression.” That’s as good a brief description of the thing as I’ve come across.

Also, Marion Montgomery has written a lot on this subject, calling it something along the lines of “the attempted triumph of will over nature by gnosis.”

Art being that which requires empathy with the subject, and technique being that which requires only skill. Art is that which is according to human scale (even Chartres or Notre Dame), and technique that which dwarfs humanity (as Boulder Dam). Albert Speer designed Germania to dwarf the human soul. Somehow, none of the buildings of antiquity managed to do that.

Alas, the battle between art and technology has been fought and won — by technology. Even something so intimate as sex has been dehumanized by the technology of porn.

And, capitalism, either of the individual entrepenuer or of the State, is busy with its technoloty of wealth, destroying the last obstacle to universal domination, the Family.

Alas, alas Babylon, we have not long to wait — there will be no “apres nous” before the deluge.

Comments are closed.