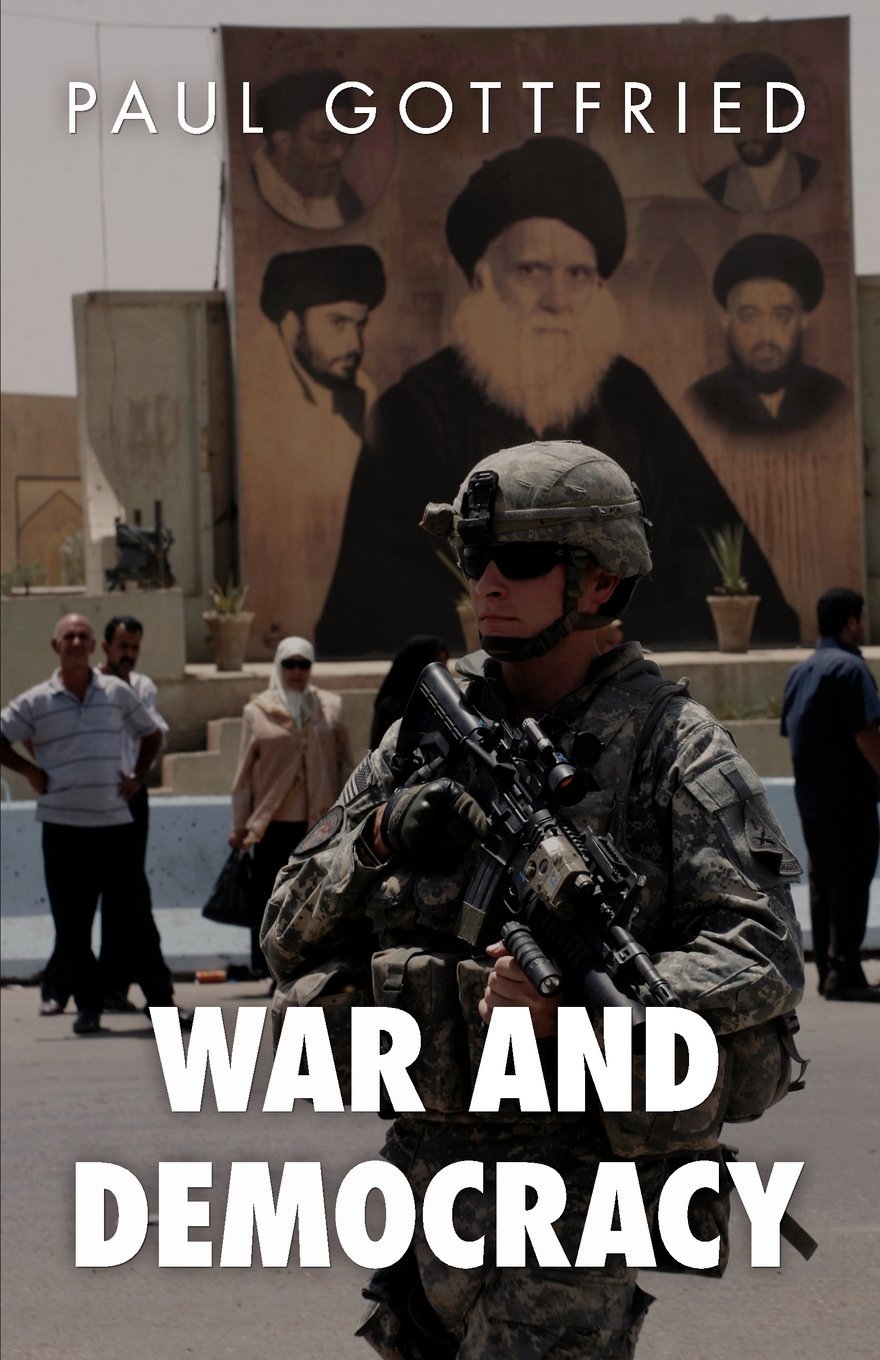

War and Democracy

by Paul Gottfried

Arktos Media Ltd

170 pp., $21.00

In this slender volume Paul Gottfried addresses everything from the influence of ancient Greek thought on Oswald Spengler, to the influence of Zionism on US foreign policy, to the influence of leftist theorist Herbert Marcuse on Gottfried himself. Quite aside from its therapeutic value in a world excruciatingly saturated by chatter, War And Democracy is educational: Gottfried’s wide range of intellectual interests ensures that the attentive reader will learn quite a bit about the West, past and present.

The diversity of topics notwithstanding, there is nonetheless unity to be found, insofar as most of the essays relate at least tangentially to the book’s title. Whether Gottfried is contemplating the Molnar–Benoist debate over Christianity’s relationship to messianic secularism, or pondering diplomat George Kennan’s fascination with the Kriesau Circle and July 20 Plot, there is always in the background a grim underlying theme: “[T]he US is moving along the same trajectory as Western and Central Europe, away from a bourgeois or older Western civilization, toward some form of post-Christian, postmodern culture presided over by a vast administrative apparatus.” Coming as it does from a man familiar with the work of James Burnham – the political philosopher whose 1941 The Managerial Revolution helped inspire Orwell’s 1984 – this pessimistic conclusion is no surprise.

And this conclusion is difficult to refute, especially given that many on the so-called Right today are even more eager for the new world order than are their ostensible adversaries. As Gottfried is one of the reactionary founding fathers of what is sometimes called “paleoconservatism”, he naturally gives attention to the ascendancy of these faux-conservatives. The rise and eventual hegemony of “neoconservatism” over the conservative establishment, implies Gottfried, is best seen in the ironic context of the Cold War coalition against Bolshevism: “In the 70’s and 80’s, the American Left swarmed with despisers of the U.S., which was then engaged in a global struggle against the Soviets and their proxies. The Right by default became America-boosters, in whose ranks coexisted both traditional anti-Communists and neo-Jacobins. But it was the neo-Jacobins who by the end of the Cold War were able to define the moral substance of the struggle against the Soviets as a global democratic crusade tied to a particular state representing a political creed.” This “global democratic crusade” marches on, bearing an eerie resemblance to “the Communist goal of bringing about world harmony through worldwide socialist revolution.”

Gottfried coolly scrutinizes the “rogue notion” that America is called to democratize the world. Like other critics of the modern ideé fixe such as Chilton Williamson and the aforementioned Alain de Benoist, Gottfried raises the question of what politicians actually mean when they employ the god-word democracy. As often as not, American pundits who accuse their foreign and domestic enemies of being “undemocratic” have but a feeble grasp on what such an accusation might mean. In particular, Gottfried dryly observes, the new breed of Republican intellectual offers “a definition of democracy that is far from rigorous.”

Everything we should value – free markets, pluralism, periodic elections, easy access to citizenship – are essential for the received concept of democracy. Such a conceptual hodgepodge indicates a lack of familiarity with one of Aristotle’s key distinctions in Metaphysics (Book Five) between what is essential and what is accidental in a particular being. There is nothing intrinsic to popular government that requires a free market or that protects private property against political confiscation. Pre- and non-democratic governments existed almost universally until the twentieth century, and both arrangements in the Western world protected private property and supported capital formation.

[Also left out of this] celebratory picture [is] what is ideologically inconvenient: that Western democracies have now developed gargantuan public sectors, are turning into supranational bureaucracies, tax their subjects up to half or more of their earnings, undertake massive social engineering, throw dissenters into jail or ruin them professionally for politically incorrect remarks, and, in short, behave less and less like constitutional regimes.

We are intellectually careless when we assume democracy has a necessary connection with, say, consumer capitalism and constitutional order, or with inclusiveness and tolerance. The point is not how one may regard any of these things – or democracy itself – but that Americans increasingly seem like figures in some darkly humorous Platonic dialogue, carrying on a ferocious political tug-of-war for ideals they have hardly bothered to think about, much less define. As often as not self-proclaimed democrats have more respect for their own pet abstract idea of “the people” than for any actual people. Perhaps it would be better for Western rulers to frankly discard cant about popular government, instead of disingenuously employing it as a rubber stamp for decisions imposed by Eurocrats or federal judges?

Unflinchingly, Gottfried ties a plethora of other sensitive, complex subjects into his central theme. How the word fascist is, like democracy, ahistorically and mindlessly misused, and why neoconservatives’ fanatical promotion of universalist pluralism is incompatible with their commitment to Israel’s survival. For a sane man the modern West is not a pretty picture, and the warning of War And Democracy is well encapsulated by words from Gottfried’s introduction: Quem Deus vult perdere prius dementat.

I am on Easter break; I have read many of Dr. Gottfried’s works. This one is a must for this next week. It will be counted as a FPR Easter gift to me, with the FPR being an agent of Providence.

“[T]he US is moving along the same trajectory as Western and Central Europe, away from a bourgeois or older Western civilization, toward some form of post-Christian, postmodern culture presided over by a vast administrative apparatus.”

At what point is it safe to say the US is no longer moving toward such a culture, but has in fact actually arrived at it?

I ordered the book, and I have already read it. Provoking and so because of the content and the style of the essays.

I ordered as well — got it the other day, but have only skimmed it here and there. Gottfried’s ‘Liberalism’ trilogy is very much worth reading and re-reading.

Comments are closed.