Despite constant speculation about public libraries’ “relevan[ce] in the digital age,” and serious budget cuts caused by the recent recession, the American public library is not in crisis. Local governments have made no effort to drop libraries as a basic municipal service. According to the Institute of Museum and Library Services’ most recent “Public Libraries Survey,” the total number of public libraries in America has been growing, not declining.

But libraries do have a problem, in that it has become less and less clear what precise public service they exist to provide. Is it cultural enrichment, recreation or information? Most discussions about libraries’ future tend to focus on how they should adapt to technological developments such as the e-book and scholars’ growing reliance on the internet to do most research. These technological questions are secondary. In order to judge how technology may enhance or detract from their core purpose, libraries must first decide what that purpose is.

That’s no easy task, but one way to begin thinking about what libraries are for is to consider whether they should be more like museums or community centers. In recent decades, libraries have become increasingly indistinguishable from the latter. Librarians promote their events, free public internet access, job search assistance for the unemployed and public meeting space, much more than they do their circulating and research collections and quiet study space. These all qualify as “public services,” but it’s by no means clear that libraries should perform them. By all means, let’s combine functions in the name of cost savings and enhanced efficiency. But not if the functions in question are incompatible. Librarians are not trained to be social workers. Community centers are not conducive to quiet study. They tolerate loitering and bustle. Many libraries now designate special sections of the building for “quiet study,” as if the entire library should not be for quiet study.

Museums provide the public with opportunities for enrichment, meaning education without any directly practical application. Libraries now betray little evidence of a concern with enrichment. Take acquisitions, which are determined largely by what’s popular and/or heavily promoted by publishing houses. As the director of the White Plains, NY library recently explained on publishersweekly.com, most librarians place first priority on “books that will offer a good return on investment, and keep our customers happy and coming back.” That clearly goes double for films (all ten of the largest library systems in America carry copies of Deuce Bigalow Male Gigolo 1 and/or 2), to say nothing of video games and toys.

Of course, the idea that libraries should entertain the public is not new. Many early library proponents in the mid-19th century believed that the public needed wholesome alternatives to the saloon. There was also a thought that newspapers and low-brow potboilers could eventually redirect the common man into more edifying pursuits.

To inform the public is another purpose often attributed to libraries. At many graduate schools, “information science” has replaced “library science” as the standard degree pursued by aspiring librarians. Large city libraries serve as official repositories for federal government publications, and even the most modest libraries in small communities hold local history and genealogical materials. In the 90s, conventional wisdom held that the public would require assistance in navigating the Internet, and that librarians should meet this need. Of course, Google has since rendered this idea quaint. Over time, the amount of information available on the Internet has increased, as has the ease in sorting through it all. (In Enrichment, a valuable history of the American public library, Lowell Martin argues that serving as the go-to source for information on politics, business and other vital matters has always been more of a dream of librarians than a reality.)

How did we get here? When did it become widely assumed that libraries had to drastically dumb themselves down and/or stop being libraries to ensure their survival? Did librarians drive the change? Or was it library boards and city governments exhorting librarians to care more about “customer service,” just like public transportation agencies regularly are? Technological developments may have played a role, but, more likely, a shift in attitudes about what it means to serve the public drove these changes in libraries’ sense of purpose.

The task ahead for library policy should be to revive the traditional debate about “recreation or enrichment” which will require two things. First, libraries and their advocates should obsess less over what to do about e-books, online databases and suchlike. As n+1’s Charles Petersen notes in his excellent two-part series about the New York Public Library (NYPL)’s “Central Library Plan,” the future of technology is uncertain and libraries have been wrong before. The NYPL opened its Science Business and Industry Library branch less than 20 years ago but now plans to sell it off, as the CD-ROM technology around which the branch was designed has since become obsolete. To ensure optimal use of limited public resources, libraries should be late adapters, not early adapters.

Second, libraries should think of themselves as more like museums and less like community centers. The pendulum has swung too far: whereas libraries’ identity used to be defined by a lively debate over whether they should provide edification or diversion to the public, they are now too content to amuse. Like museums, it has long been the good fortune of libraries to enjoy consistent and broad public support despite the fact that only a minority actually visits them. True, libraries are taxpayer-supported and museums are private charities, but no one seems to object to taxpayer support for parks, whose purpose has much more in common with museums than police, fire and school departments. The library may not qualify among the more “essential” services of local government, but we are clearly committed to it and can clearly do better.

Stephen D. Eide is a Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute’s Center for State and Local Leadership and Editor of the blog publicsectorinc.org.

Stephen,

A thoughtful essay, with some good ideas–you’re surely correct that libraries shouldn’t waste so much time and money working for technological relevance. But I think you’re misunderstanding the importance of “community centers,” and for that matter just what such a thing can be. (You talk about “entertainment,” but my primary experience with our local public library’s community outreach programs have been all about “enrichment,” whether it be hosting book groups or providing candidate forums during election years.) The fact that you say “no one seems to object to taxpayer support for parks, whose purpose has much more in common with museums than police, fire and school departments,” really strikes me as curious–surely parks are far more like community centers, giving local groups a space for fun and celebration and public displays, than are are like museums, aren’t they?

Libraries provide the opportunity to learn what I want to learn in a capital driven country. Or else I pay someone money. If no one ever uses it, that it is there and offers the opportunity of self-betterment is a definitively necessary service in what is called a land of opportunity. At least in my town that also means that none is so poor that they cannot access the Internet. I have serious prospects of increased poverty but will at worst be only a bike ride from Front Porch as well as Solzhenitzyn or Charles Williams.

Public Libraries are the most civilized thing we do in this “Money doesn’t talk, it swears” plutocracy (a form of government and a religion.)

Mr. Fox,

Thanks for your comments. Just to clarify one thing: this is not an argument that community centers or parks are undeserving of public support. The question is what is their function, and what is the function of a library, and are these functions close enough to merit being combined in the same place and run by the same staff?

Public administrators concerned about making government cheaper and more efficient want to combine as many functions as possible. I am generally sympathetic to this approach. I believe, for example, that many communities should combine their police and fire departments. But, in the case of libraries, I’m less sold. To begin with, efficiency arguments about libraries are often made by people who do not themselves use libraries. And I also have a sense that librarians lack for pride in their profession and have become too eager to adapt to build up support for themselves in the community and protect their budgets.

Book groups I don’t object to but I’m actually not sure about the candidates’ forums. Yes, they easily qualify as “enrichment,” but enrichment can occur outside the library as well. Why not, then, political meetings of any kind? In Worcester, MA, there was a controversy a couple years ago about whether a white supremacist group should have the right to use the library’s meeting space. It was, for me at least, a “teachable moment” about the dubiousness of libraries’ commitment to providing public meeting space.

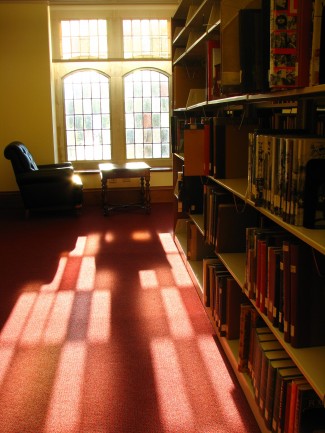

Here’s one way to put the question: say you’re on a local board charged with reviewing architects’ plans for a new library. Your funds are not limitless. What do you go with: a handsome reading room, suitable for quiet study and research, or space for events and meetings. The trend in library architecture has clearly been away from the former and towards the latter, but I’d vote for the reading room.

Mr. Eide–Since everything you mention as a function of the public library has been going on since before my 30-plus-year career as a librarian (primarily in library journalism) began, I wouldn’t count on anything changing soon. Librarians themselves by and large accept all those functions and look for more to assume, usually debating among themselves the appropriateness to their profession of each new function from the moment it is proposed and ever after. Perhaps the one thing they continue to stoutly resist is babysitting, both of temporarily abandoned, ill-mannered children and obnoxiously insane or inebriated adults. Perhaps the one function they don’t want to lose is “information service”, aka “reference service”, though most acknowledge that the Internet has greatly decreased demand for it. A sizable number have, for the past two decades, at least, focused on “reader’s advisory” service instead, so that they will be able to help patrons in following their reading interests. The rub there is that to provide such service they have to know or learn about discrete kinds and fields of literature and entertainment/art. Fortunately, that’s a pleasure for most librarians (the ones who find it not their cup go into administration, I suppose, and earn more than their public-service colleagues) and often makes unpretentious and congenial experts of them.

Speaking entirely personally, I shall be satisfied with my public library (actually, libraries, since I live in the Twin Cities, with branches of the St. Paul and the Hennepin County public libraries within walking and 15-minute-driving distance, respectively) as long as they keep in circulation the older, often out-of-print books I’m interested in. So as far as architecture goes, I’m more interested in plenty of shelving space than in big reading rooms.

Mr. Eide,

Thanks for your response (and my apologies for the informality of my own!). We probably don’t disagree much, but still, I see a difference in emphasis here. You seem rather focused on the idea that librarians themselves have forgotten (or been obliged by budget pressures to make themselves forget) their core purpose of “enrichment,” and thus have acquiesced to the omni-present top-down demands for multi-use efficiency. I don’t doubt that such is often the case. But I wonder if you aren’t speaking with perhaps unwarranted confidence that the sort of distinctions which concerned librarians have to (and ought to) make will be as clear as a choice between a reading room (how “handsome”? how much money will go into the stuffed armchairs? will there be wireless internet access?) and “space for events and meetings.” I really think the lines are more finely drawn than all that. Remember that the dispute you mention in Massachusetts, if it didn’t come up at the local library, would have come up at the local community center as well. It seems to me that democracy in a pluralistic society is going to be messy wherever it takes place, and making use of library spaces in displaying and enabling that messiness won’t, I think, hurt the integrity of the library’s mission at all (not so long, at least, as the bare-bones information and access services which Ray Olson mentions continue to be provided…if a library got to the point where community opportunities and entertainment were really interfering with those baseline expectations, than I’d see your point more clearly).

You’ve got it all wrong. The main purpose of a library is to be a repository for local history and genealogy resources, and a place to use them. In some towns a historical society tries to fill that role in a separate building, but usually their archives have quite limited hours. A good library is one where I can come from out-of-town and be directed to the Michigan Room (or Indiana Room, or whatever they call it in other states). The stuff that takes place in the rest of the building is filler, fluff – OK as long as the main function is supported.

Oh, and as for combining the roles of police and fire fighting – I’m against it. It gives people the impression that policing comes under the heading of public safety, which notion leads straight (albeit slowly) to totalitarianism.

Hmm. Interesting. I thought the primary purpose of libraries was to encourage reading by the provision of books and reading space, because society realizes literacy is essential to being a good citizen and not everyone has money to buy their own storehouse of books. A central repository helps a community’s members read.

Everything else, including internet access and other community events, though valuable and in need of public funding (public internet cafes, etc.), is tertiary to this primary purpose.

In my opinion you have “buried the lead” by stating at the very end of your well-written piece, “True, libraries are taxpayer-supported and museums are private charities…” As the director of a small library in a town of just over 1,300, I am charged with expending the tax revenue allocated to the library by elected town officials to develop a collection of materials for residents to read, view and hear. I refer to my library users as “patrons” because through the payment of their taxes, that is what they are.

I take a great deal of pride in being able to provide my library patrons with excellent service and I believe it would be irresponsible of me to spend their money on books that circulation history shows they do not want to read. While I might personally lament the fact that the Twilight- Breaking Dawn, Part 2 DVD will circulate at least five times more than Hilary Mantel’s Bringing Up the Bodies (2012 Man Booker Prize winner), it is not my place to pass judgment on my patron’s preferences.

Libraries exist to provide free and equal access to information, be it in a book or on the Internet, because, “A democracy presupposes an informed citizenry (http://www.ala.org/offices/oif/statementspols/corevaluesstatement/corevalues).” That means free and equal access to both James Patterson and Allan Bloom. You will not find many who argue that Bloom does a lot more for educating the citizenry than does Patterson. Nor will you find many librarians who, faced with rising book costs and shrinking budgets, would not buy Patterson first and perhaps never replace their tattered copy of “The Closing of the American Mind (a best-seller in 1987!).”

So, perhaps it is not libraries that are being drastically dumbed down but the taxpaying public they serve? A subject for your next post?

With great respect,

Mindy Flater

Comments are closed.