Rock Island, IL

Looking back in the 1830s at the Maypole event of 1628, about which both William Bradford (Of Plymouth Plantation) and Thomas Morton (New English Canaan) wrote, Hawthorne said, “There is an admirable foundation for a philosophic romance.”

And such a romance did Hawthorne produce, which he titled “The Maypole of Merrymount.” It is a fictional account of the clash between the separatist settlers at Plymouth and the less religiously minded traders gathered first about Captain Wollaston and then Morton himself in a prosperous and fast-growing colony that the separatists both disapproved of and feared.

In Hawthorne’s tale the narrator tells us that the future complexion of New England is at stake: jollity and gloom contend for a kingdom. By the end of the allegory (as Hawthorne also called it), systematic gaiety gives way to gloom, as, apparently, it always will: the Anglican revelers at the maypole come to grief at the hands of the strict separatists.

We are accustomed to granting Hawthorne his philosophic romances and to chuckling at Morton’s parody and maybe to yawning at Bradford’s “history.” But there is just cause to see an allegory in Bradford’s account as well—more, perhaps, than in Hawthorne’s, though for reasons very different from Hawthorne’s.

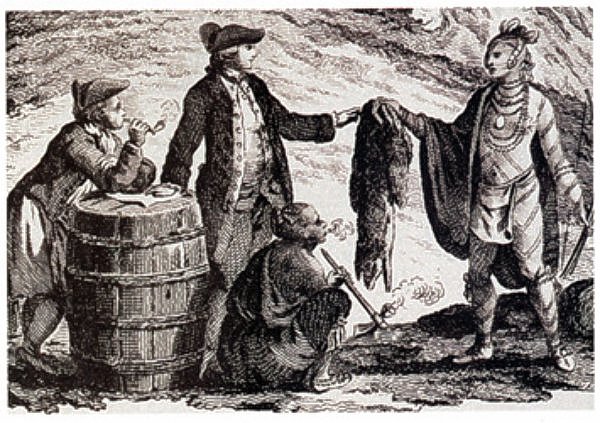

One of Bradford’s complaints against Morton is that to maintain his “riotous prodigality and profuse excess”—that is, “hearing what gain the French and fishermen made by trading pieces, powder, and shot to the Indians”—he armed the already nimble-bodied and quicksighted Indians with guns,

so as when they saw the execution that a piece would do, and the benefit that might come by the same, they became mad (as it were) after them and would not stick to give any price they could attain to for them; accounting their bows and arrows but baubles in comparison of them.

There is an allegory of sorts here that, had Hawthorne been interested in it, would have made his own rendering of the account a very different tale indeed. In a few short words Bradford provides all the main features that make up the story of industrial goods: someone who stands to benefit from hawking a new thing convinces someone else that he needs it; once that someone else sees what it can do he becomes mad to have it at any price. And, finally, once in possession of it, he looks contemptuously at the old thing, accounting it a mere bauble.

The only thing missing here is the commentary: the new thing not only replaces the old thing; it destroys the knowledge, ways, and means that go along with using it. That is, it replaces old goods and skills. And in the end, depending on how much and how quickly it can do what it does, it may replace people as well.

I noticed recently that a certain hawker of cell phones has unabashedly incorporated the contempt of which Bradford wrote into an new ad campaign: a person in the ad, if I remember correctly, says to another person that “2007 just called and it wants its old cell phone back.”

And I can remember a twelve-year-old neighbor boy standing in my house twenty-five years ago or so looking with the scripted contempt (the boy was a quick study) upon the Mac Classic that I wrote my Ph.D. thesis on. “Why don’t you get rid of that thing?” the kid snarled. “It’s ancient.”

I—who still have a pair of boots purchased in 1980!

Wendell Berry, in The Unsettling of America, quotes at length from Bernard DeVoto’s The Course of Empire to illustrate the very same point Bradford was trying to make. “The first belt-knife given by a European to an Indian was a portent as great as the cloud that mushroomed over Hiroshima. . . . Instantly the man of 6000 B.C. was bound fast to a way of life that had developed seven and a half millennia beyond his own. He began to live better and he began to die.”

The main trade goods, Berry says, were “tools, cloth, weapons, ornaments, novelties, and alcohol.” Their sudden availability changed everything: handicrafts, the methods of hunting and waging war, marriage customs, the work traditionally performed by women, standards of wealth, and mobility.

DeVoto says, “In the sum it was cataclysmic. A culture was forced to change much faster than change could be adjusted to. All corruptions of culture produce breakdowns of morale, of communal integrity, and of personality, and this force was as strong as any other in the white man’s subjugation of the red man.”

Berry’s point is to show that this revolution “did not stop with the subjugation of the Indians, but went on to impose substantially the same catastrophe upon the small farms and the farm communities, upon the shops of small local tradesmen of all sorts, upon the workshops of independent craftsmen, and upon the households of citizens.”

This revolution, Berry says, is still at it, and the economy is still essentially that of the fur trade, “still based on the same general kinds of commercial items: technology, weapons, ornaments, novelties, and drugs.”

The one great difference is that by now the revolution has deprived the mass of consumers of any independent access to the staples of life: clothing, shelter, food, even water. . . . Commercial conquest is far more thorough and final than military defeat. The Indian became a redskin, not by loss in battle but by accepting a dependence on traders that made necessities of industrial goods. This is not merely history. It is a parable.

The example of Hawthorne suggests that history is never merely history. The only question is, what details do you select from that history to tell what kind of parable?

Melville detected a certain “blackness” in Hawthorne stemming from a sense of innate depravity and original sin from which, Melville said, no deeply thinking person is every wholly free. Anyone who would account for evil in the world would have to posit the “T” of TULIP to strike the uneven balance.

It was perhaps this “blackness” in Hawthorne that accounts for the triumph of gloom over gaiety in his version of the Maypole event. But although Bradford’s account of Morton’s gun trade might lead another romancer to write a different version, I wouldn’t recommend he scrap the depravity. Man is a damned mess much in need of grace, as Norman Maclean once said. If history teaches us anything it teaches us that.

Interestingly enough, Bradford ends his account of the year 1632 by noting that as the people of Plymouth Plantation grew “in their outward estates, by reason of the flowing of many people into the country” and the rising price of corn and cattle “by which many were much enriched,” there was little to hold the community together:

They could not otherwise keep their cattle, and having oxen grown they must have land for plowing and tillage. And no man now thought he could live except he had cattle and a great deal of ground to keep them, all striving to increase their stocks. By which means they were scattered all over the Bay quickly[,] and the town in which they lived compactly till now was left very thin and in a short time almost desolate.

This is not merely history. It is a parable.

https://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2013/03/history-is-bunk/ History is bunk revised?

Revised from deep within the cloud of amnesia.

[…] Did all our consumerism start with the Indian trade? Jason Peters describes how industrial goods can displace a culture in “History as ParableR… […]

“TULIP” was something I had to look up; I’d never heard of it before. The concept of double predestination was the only thing I’d really remembered from the time we spent studying Calvin.

I have nothing to add, really, other than that I found the article to be very interesting and Berry’s points (as well as Maclean’s quote) to be true. Man’s nature (particularly in regard to his need for grace) has not and will never change. I suppose that men have been fascinated and taken in by novelty in every age as well, though it seems we’re certainly worse in that regard than our grandfathers were.

Comments are closed.