Louisville, Kentucky. I am thinking about the rhetoric of this almost-war, as the Obama Administration has paused (at least for now) in its push toward conflict with Syria.

While Mr. Obama’s hesitancy and change of mind has put his fundamental weakness on international display, still, from my perspective our failure to strike has been a mercy—and not only because it is very uncertain that our intervention there will improve life for the Syrians or their neighbors. Not to mention ourselves.

Here in the States, Mr. Obama’s decision to go to Congress for a supporting vote, after making it clear the week before that he would do no such thing, undermined his contention that he had no legal need to bother with the House and Senate. As a practical political matter, Mr. Obama blinked. This may mean there has been some strengthening of the argument that Congress should retain, jealously, its right to declare war, as stated in the Constitution.

Rhetorically, however, Mr. Obama has not given up his asserted Executive prerogative to declare war if he chooses. Here’s what he said in a September 4, 2013, news conference with the prime minister of Sweden:

“And I would not have taken this before Congress just as a symbolic gesture. I think it’s very important that Congress say that we mean what we say. And I think we will be stronger as a country in our response if the President and Congress does it together. As Commander-in-Chief, I always preserve the right and the responsibility to act on behalf of America’s national security. I do not believe that I was required to take this to Congress. But I did not take this to Congress just because it’s an empty exercise; I think it’s important to have Congress’s support on it.”

He is correct to say he should have Congressional buy-in for what is a necessarily violent and expensive decision. But while Mr. Obama grants Congress the right (even the obligation) to support his decision, he does not admit that Congress has the right to quash that decision—even though the power of Yes means little if there is no corollary possibility of No.

Mr. Obama’s adherents have made similar arguments about Executive prerogative. One good example is a recent column in the Wall Street Journal by Brookings Institution fellow (and longtime Democrat) William Galston. Giving one of several answers to his own question of how the President could justify his right to go it alone on such a matter as starting a war with another country, Mr. Galston wrote:

“And he could insist that if he failed to act in Syria just because Congress said he should not, he would pass on to his successor a diminished presidency that would upset the nation’s basic constitutional balance.” (Emphasis added.)

Friends of mine have argued for years that the Constitution is a dead letter, and “originalists” or “textualists” have my sympathy when they bemoan its legal irrelevance. But I have to agree that the more liberal interpreters are right to say that our Constitution is a living document. Every nation’s government is remade by succeeding generations. Our laws hold our past in their language, but in our current reading of them we express our belief of what the law should be. Like our liberty, good legal standards can only be kept by dint of will and vigilance. Hence we have the Constitution that we, in aggregate, seem to want.

Here is the Constitution we had. The pertinent language is from Section 8:

“The Congress shall have Power…

To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offenses against the Law of Nations;

To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

To raise and support Armies…”

None of this is hard to understand; none of its diction is ancient, with the exception of the term “letters of marque” (an official commission granting the holder the right to what would otherwise be called piracy). The Constitution is written throughout in what is still lucid English. But that does not mean that men such as Mr. Galston or Mr. Obama (and plenty of Republicans, too) have hesitated to translate its straightforward, 18th-century English into the murky, mutable shadow script of executive power-grabbing and penumbra, where words are deemed to mean precisely what they do not say.

The logic of an overweening Executive takes us back to one of the other bad arguments for this intervention: that our honor, through Mr. Obama’s honor, is a stake. The “thin red line” Mr. Obama referred to in an August 2012 press conference was a promise this entire country was told it needed to keep. Set aside for a moment the fact that Mr. Obama has himself denied that those words obligated him and his country alone (“the world set a red line”). Set aside the other fact that in that 2012 press conference he promised a strong reaction but stopped short of promising air strikes.

The rhetoric of those remarks took on a life of its own, and while it is likely true that a President’s promise, unkept, looks weak internationally, surely this is a perfect example of the ridiculousness of a single man holding three hundred and thirteen million of his fellow citizens captive to a threat he made by himself.

A Congressional declaration of war should always be necessary because such a momentous decision should never rest on the shoulders of one person. It is too much power and painful responsibility, that one man should be able to embroil thousands directly, and millions indirectly, in a fight that will always be easier to start than to finish.

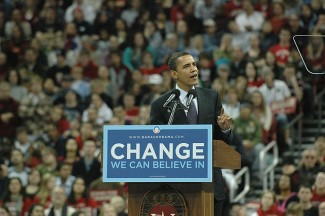

Photo credit: Lost Albatross

Part of the problem is the modern tendency by Congress to fund a massive standing army. And, as they say, where you have a hammer every problem in the world begins to look like a nail.

In a world where the United States faces no external existential threats, Congress could make a rational decision to limit the US military to an essential core that cannot conduct war without additional appropriations. The world would be better for it.

I think Wilton hit it on the head. As long as congress funds an army and a navy, the Commander in Chief will conceive of his ability to order that army and navy wherever he thinks it needs to be rather expansively.

Refusing to fund military expenditures has always been the most effective means congress had for keeping control of what the president could commit to.

There are some rather old precedents though. With a very limited military establishment, President Polk was able to provoke a sufficient clash with Mexican forces that enough congressmen felt obliged to “support our troops” that he was able to launch a full scale war. One wonders how much Mexican immigration we would have today if the Mexican economy had been able to develop the resources of California, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico…

Abraham Lincoln took measure to respond to the rebellion of 1861 for months before congress met and retroactively ratified what he had done. Arguably, he had no choice, doing nothing would have been a decision in itself.

Its hard to say how much of a military we could do without in the present world, without being in danger of actual threats from nations that did maintain large standing armies. We wouldn’t have the time we had in World War II to build up our forces. Possibly congress could severely limit the number of foreign duty stations funded, keep a lot of troops in ready reserve in the continental US, Alaska and Hawaii with rotations abroad, and limit the funding for fuel to keep more than a certain number of naval vessels in foreign waters… but its not clear how well that would work either.

Of the 280 foreign military operations the US has carried out over its history (that’s Yale historian Harry Stout’s number, as of 2009), precisely five have involved official declarations of war. Another thirteen have been authorized by Congress. The rest just happened by executive order.

No president has ever been threatened with impeachment because he ignored Congress (not even Richard Nixon after Congress repealed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1971). Never has the House of Representatives voted to defund an army involved in a foreign war (it’s required to reappropriate funds every two years).

Nor has there been any substantive movement whatsoever to amend the Constitution to restrain the executive’s war making prerogatives. Not even the 1973 War Powers Resolution attempted to remove his power to initiate conflict.

What this means is there has been no “presidential power grab.” Congress and the American people have acquiesced in this system since John Adams waged the Quasi War and Thomas Jefferson attacked the Bey of Tripoli.

Like it or not, Obama’s assertion of presidential power stands on a firm foundation of precedent. If you want to alter our system, it’s going to take more than a blog post.

More here:

http://ricks.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2013/09/25/all_power_to_the_constitution_what_tom_meant_to_say_about_amb_powers_speech

Oh, now isn’t that special, Mr. Galston claiming a lack of constitutional balance if the Executive is not able to countermand the Constitution and declare vague references to national security in order to conduct war-like activities not officially declared war.

Parsing the Constitution is a National Past Time.

Having just completed Kaplan’s book “The Revenge of Geography” and its final chapter, one wonders at our idiocy regarding Mexico as well as our continuing idiocy regarding Iran. We are a Super Power that continues to flail about and act in an inchoate manner.

Lastly, a Chief Executive who does not act Presidential should not complain about the problems of dealing with his opponents. This President is a prime example of the Peter Principle. His opponents are simply paid off retainers to a Federal Suicide.

American government was once fleet and mobile. It is now a tied hog, ready for the slaughter.

Comments are closed.