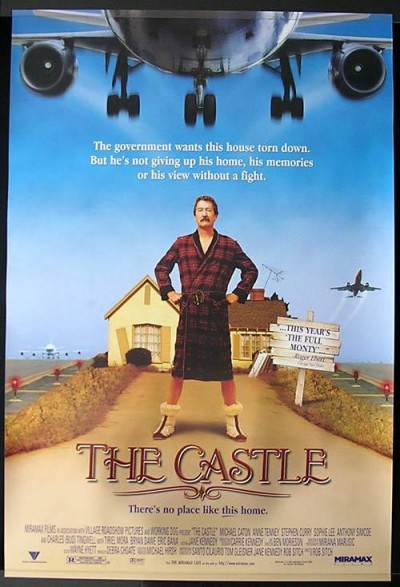

Hidden Springs Lane. After too long, I finally got around to watching The Castle (1997), a film recommended by FPR’s Jeff Polet. It’s a film you probably haven’t heard of let alone seen. It’s an Australian comedy that tells the story of a working class family who live in a humble home beside the Melbourne International Airport, which, as the narrator Dale Kerrigan points out, “will be very convenient if they ever have to fly one day.” In addition to the airport and low flying airplanes, the house is almost directly beneath a huge power line, which, Dale muses “might put some people off, but not Dad. He reckons power lines are a reminder of man’s ability to generate electricity. He’s always saying great things like that. That’s why we love him so much.” The backyard, incidentally, was filled in prior to construction of the house, but there’s nothing to worry about. “Do you know anything about lead?”

Despite the obvious drawbacks of this particular piece of real-estate, the family is almost as devoted to it as they are to each other. The pater familias is Darryl Kerrigan, who drives a tow-truck and adores his wife, Sal, whose culinary creations—from meatloaf to icing on a sponge cake—never fail to amaze him. The Kerrigans have three sons: Dale, the youngest, who digs holes; Steve, who buys used items (from pulpits to jousting sticks) and who his Dad calls “an ideas man”; and Wayne who, although he is serving time in prison for armed robbery, is dearly loved and missed by the family. The Kerrigan’s one daughter Tracy is, Dale reports without a trace of jealousy, Darryl’s favorite. She has recently married a Greek kick-boxing accountant played by Eric Bana (this is his first film).

All is well at 3 Highview Cresent until one day the Kerrigans receive a notice that their house, and several others on their street, is being “compulsorily acquired.” As Darryl knowingly explains it to his family, this means they’re going to acquire it compulsorily. They soon learn that the land their homes occupy is needed for a planned expansion of the airport. Everyone is fair offered market prices (of course the market value of a house beside a major airport is not good), but not surprisingly, no one wants to leave.

Darryl Kerrigan emerges as the champion of this small band of neighbors who attempt to hold on to their homes. At first, Kerrigan is dumbfounded that his home can be taken without his consent. At an initial hearing, he serves as his own attorney, and though his arguments make perfect sense to him, they don’t make any reference to the law. When the judge asks for his case, Kerrigan makes a simple appeal to justice.

“You just can’t walk in and take a man’s house.”

The judge, a bit confused, asks if Kerrigan is disputing the amount of compensation. Kerrigan replies:

“I’m not interested in compensation. I’m saying that you can’t kick me out.”

The judge, seemingly unaccustomed to such a direct approach then asks Kerrigan for his argument.

Darryl: “That’s it. That’s my argument. You can’t kick me out.”

Judge: “And on what law do you base that argument?”

Darryl: “The law of bloody common sense!”

Kerrigan is warned by the judge, who then suggests that Kerrigan has offered no evidence to refute the right of the airport authority to take his property.

Darryl: “No evidence? (pauses to gather his thoughts). It’s not a house, it’s a home. A man’s home is his castle…You can’t just walk in and steal our homes.”

Judge: (exasperated) “You will be compensated.”

Darryl: (frustrated) “I don’t want to be compensated. You can’t buy what I’ve got.

And therein lies the crux of the conflict: a law based on the assumption that all things have a fair market price and that the loss incurred by being forced out can be compensated with cash. Kerrigan knows better, and it is the singular charm of this film that it makes the audience grasp how the love of this working class bloke and his family have made a rather shabby and non-descript house a home worthy of love.

Kerrigan’s solo attempt fails to save the family home, so he enlists the help of a small-time attorney, Dennis Denuto—the same lawyer who unsuccessfully defended Kerrigan’s son Wayne. At an appeals hearing in a constitutional court, Denuto, who is painfully out of his depth, cannot indicate a particular section of the constitution that is being violated; however, he helplessly claims that “it’s just the vibe of the thing.” Clearly such an argument isn’t going to fly, but to avoid any spoilers, let me simply say that things get more complicated as we learn that a powerful corporation is behind the airport authority, and as Denuto explains: “These people are used to getting their way.”

The Castle—sort of an Aussie mash-up of Napoleon Dynamite, It’s a Wonderful Life, and Perry Mason—is a charming, quirky film that reminds us of the simple, though profound, goodness of home, that the best things in life cannot be purchased or sold, and that power and justice are not always on the same side. It definitely merits a place on FPR’s List of Films. What other films deserve a spot?

Hoosiers!

Bill,

I agree. Hoosiers needs to be on the short list.

Places In the Heart

The Straight Story (David Lynch)

The Road Home (Zhang Yimou)

The Trip to Bountiful (Peter Masterson)

The Burmese Harp (Kon Ichikawa)

Also the documentary about Sacred Harp singing, “Awake My Soul.”

Babette’s Feast

As an Australian, I can testify to the powerful hold this film has on the national psyche. Several phrases have entered our everyday vocabulary. One is quoted above – ‘It’s the vibe,’ another is ‘Oh, the serenity,’ and, if you are given a particularly fantastic present, the giver will be absolutely gratified to hear, ‘Well, that’s going straight to the pool room!’, Oh, and another one, when someone is charging too much for something we instruct each other, ‘Tell him he’s dreaming!’ I can’t think of any other movie that is so extensively quoted in daily life, and understood by everyone.

@RobG, The “Awake My Soul” that Mumford and Sons recorded?

no — same title, different song. I’m fairly sure that the Mumfords’ song of that title is an original song written by them.

Copperhead.

The Royal Tenenbaums

Lars and the Real Girl

Tender Mercies

Breaking Away

Comments are closed.