I don’t often disagree with my old friend Michael Austin, partly because he’s much smarter and much better read than I, and partly because he’s so thoroughly and non-ideologically committed to a moderate, pragmatic liberalism that it’s hard to get upset with any position he takes. But I’m going to take issue with his column yesterday, which criticizes the, I think, perfectly harmless and socially positive holiday which President Obama–like every president for the past sixty-plus years–has declared today, the first day of May, to be: a National Day of Prayer.

Michael sees himself very much on Thomas Jefferson’s side, who famously refused to follow the pattern of George Washington and John Adams in designating specific days for purposes of prayer, thanksgiving, and remembrance. He thinks highly of an excised sentence from Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists of Connecticut, which reads that “I have refrained from prescribing even those occasional performances of devotion, practiced indeed by the Executive of another nation as the legal head of its church, but subject here, as religious exercises only to the voluntary regulations and discipline of each respective sect.” On his reading, what Jefferson is doing here (he feels wisely) is refusing to involve government in expressions of devotion which should (he agrees) flourish only in accordance the voluntary and diverse choices and actions of the members of various religious bodies themselves. In other words, by refusing to countenance the popular call for days of prayer, Jefferson was protecting “a genuine free market for religious ideas.” Michael identifies such a free market with the “secular republic” that we are, and hence dislikes anything which “put[s] the government’s thumb on a scale where it does not belong.”

As a pragmatic liberal who happily supports our local chapter of Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, this is a consistent line for Michael to take, and I respect him for it. But I don’t really respect his argument, because to celebrate a refusal to endorse collective devotional actions in the name of ensuring a pristine religious marketplace endorses a rather blinkered notion of what people who govern themselves can and ought to be able to do.

The degree of separation which Jefferson endorsed (and which Michael endorses) in the original version of the Danbury letter would mean that any kind of religious sentiment–or indeed any moral or metaphysical claim at all, not merely just obviously sectarian ones–would probably have to be declared incompatible with the business of government. So, the civic acknowledgement of Thanksgiving Day, Memorial Day, not to mention Christmas Day and so forth–all of which are quite obviously rooted in particular historical and social events and arguments and occasions which are utterly inseparable from their particular religious (mostly–but not entirely or always–Christian) contexts–all would have to go. Some would be fine with that; I wouldn’t. Why? For many reasons–but the one most relevant to Michael’s “marketplace of ideas” argument is that communities of people, even in “secular republics” like our own (and as one who believes that attempts to think through and democratically address the problems of self-government will always involve citizens “establishing” one kind of moral and religious preference or another through their own popular actions and legislation, I confess I’m dubious that label can really mean anything), don’t navigate through such markets solely by “free argument and debate,” as Jefferson said. They use myths as well.

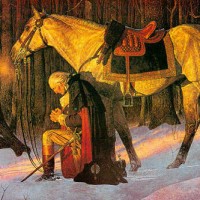

I have a print of the Arnold Friberg painting I stuck at the top of this post in my office; it was a gift from my dad. It represents a pious, devotional myth that almost certainly had no basis in historical reality whatsoever. If someone would like to use some implied message in that painting–that this nation emerged from the desperate times of the Revolution only because wise men petitioned the grace of God through prayer!–to enforce, through the collective freedoms and expectations they possess as American citizens, some sort of sectarian prayer requirement on all their fellows, I would oppose it: I’m enough of a liberal to be happy that formal, mandated school prayer was declared unconstitutional long before my kids entered the public schools. But there is a huge amount of grey area between outright theocracy, on the one hand, and discrediting the very idea that people–as members a democratic society–who ought to be allowed to organize, vote, debate, donate, march, govern, and thus define themselves, in their particular communities and contexts, in response to certain collective ideals and presumptions and hopes. And if it is the case that some of those collectively (whether nationally or only locally) expressed ideals and presumption and hopes–those myths, if you prefer–reflect elements of some particular, historically specific, religious preferences (as Thanksgiving and Christmas obvious do, and as the people who put together the National Day of Prayer task force–what with them putting a quotation from Romans 15:6 right on the front of their website–clearly did as well), is that a reason to condemn the whole enterprise? To retreat to a supposedly (but, I would argue, never truly) un-interfered with religious market?

Since accepting democracy means accepting the some sort of popularly expressed civil religion (as well as continuous arguments over such!) will always be kicking around, I say no: instead, let’s use of judgment here. That National Day of Prayer website is over the top, I agree–but is President Obama’s declaration also?

Today and every day, prayers will be said for comfort for those who mourn, healing for those who are sick, protection for those who are in harm’s way, and strength for those who lead. Today and every day, forgiveness and reconciliation will be sought through prayer. Across our country, Americans give thanks for our many blessings, including the freedom to pray as our consciences dictate….Let us remember all prisoners of conscience today, whatever their faiths or beliefs and wherever they are held. Let us continue to take every action within our power to secure their release. And let us carry forward our Nation’s tradition of religious liberty, which protects Americans’ rights to pray and to practice our faiths as we see fit….I invite the citizens of our Nation to give thanks, in accordance with their own faiths and consciences, for our many freedoms and blessings, and I join all people of faith in asking for God’s continued guidance, mercy, and protection as we seek a more just world.

Like the painting of Washington at prayer, you could look at those words and call it pious nonsense, verbiage that has no real moral weight, a cynical work of verbal art which only serves to placate a religious majority (though now, perhaps only a bare one) that likes to see their way of thinking and evaluating and living validated. And maybe it is. But it is also the product of elected representatives who believe–or who at least once believed, and to this day still do not disbelieve strongly enough to challenge this particular civic tradition–in a myth: a myth of a community seeking justice, praying for wisdom, and expressing thanks. A nice democratic myth, that is: better and more defensible, I think, than some hypothetical pure marketplace of privatized ideas and hopes and beliefs, anyway.

The Obama quote that you cite is so generic and inoffensive that it cannot be said to represent any kind of community consensus whatsoever — aside from tolerance for all religions. Even a non-theist, a Buddhist who has no concept of god, makes use of practices involving prayers or aspirations for the benefit of others. The Obama declaration does not even have a reference to god or gods.

The First Amendment’s establishment clause guards against two evils: (i) the persecution of minority religions not established as state prescribed religions, and (ii) the corruption of the established religion as it becomes an instrument of state power. The tyrant Henry the Eighth’s corruption of an established Church of England is simply the most prominent example of the latter evil.

It is hard to get either much excited or greatly offended by a National Day of Prayer that is so non-specific that it doesn’t include or exclude any religion.

Well that was interesting, thanks. I did go in a different direction, reading – this part “Let us remember all prisoners of conscience today, whatever their faiths or beliefs and wherever they are held. Let us continue to take every action within our power to secure their release.” made me think of Snowden, actually. And the strange case of Robert MacLean.

So I am sitting here thinking about the contrast between the prayer and the policies of the last couple of administrations – some of the whistleblower cases have endured for years now. And thinking of that I guess I’d say this day could be a container for the myth of some civic ideal; it could also conceal a darker idea, that the current price of religious freedom is an uncritical devotion to the public entity.

I have a hard time escaping the sense that these whistleblower trials serve some of the same functions as the excommunications of old; scapegoating and sacred violence. All of which hints of a civic religion to me. Baser in my eyes than what you described.

That’s looking at word and deed, and off topic a bit. I did wait some to post.

Comments are closed.