In “The Gift of Good Land,” Wendell Berry notes, with a tinge of regret, the largely heroic nature of the stories recorded in the Bible. “It may, in some ways, be easier to be Samson,” Berry writes, “than to be a good husband or wife day after day for fifty years.” Church tradition generally continues this emphasis on the exceptional, with martyrs like Saint Valentine and pioneers like Saint Patrick who take the gospel across stormy seas getting top billing. (As those two demonstrate, such ecclesial notice can, at times, lead to broader, if imperfect, culture recognition as well). Occasionally, though, the Church’s spotlight shines on those who live lives marked by faithful ordinariness. May 15th, the Feast of St. Isidore the Farmer, celebrating a married man rooted in the land who is said to have died at his place of birth, is one such example.

I had never heard of St. Isidore before moving into a 102 year old farmhouse last fall. The home, built by my great-grandparents, had served as a kind of family museum for decades, and exclusively as such in this century after the last resident, a great aunt, moved out in 1997. As a child, I can remember the excitement that accompanied the trip up the stairs to the attic and its wonderland of treasures. As an adult, I have come to walk those stairs again after a decade of lawyering inside the Washington, D.C. Beltway, looking to write while revitalizing some thinning Texas roots.

Apart from the wise addition of a bathroom and a more unfortunate 1970s kitchen remodel, the little house’s look and many of its contents are largely unchanged from the days when my late grandfather was a boy. Then, as now, the decorative style bespeaks pious German Catholic. Many of the Christs, Madonnas, angels, saints, popes, and priests have found new homes, but plenty still remain where they have been for generations. St. Isidore, however, is actually a new addition to the walls.

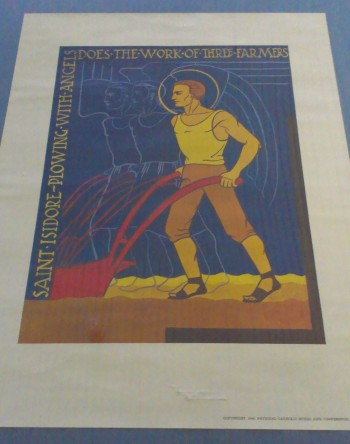

Not much got thrown away by my Great-Grandmother Annie, including the 1912 receipt for the lumber that supports the roof over my head and a tube mailer from the National Catholic Rural Life Conference that I uncovered in my quest to clean and organize the many remnants of the past. Inside was a pristine poster of St. Isidore dated 1944, its style reminiscent of New Deal murals.

The associated text reads, “St. Isidore plowing with angels does the work of three farmers,” a reference to the most common story about him. The basic tale is that Isidore, born in 1070 worked for one Juan de Vargas of Madrid, Spain, managing a field of land for a yearly wage. Isidore was known to be a man of prayer, frequently visiting local churches before the work day began. Indeed, by some accounts, he was still at prayer long after the work day had begun, a habit that led to some grumbling among others employed by the same landowner. Yet, when Juan de Vargas inquired into the matter, he saw Isidore plowing with two others beside him, beings that disappeared from sight when Juan approached. As with many of the medieval saints, the line between history and legend is often blurry. Isidore, who is also associated with other miraculous events emphasizing his generosity towards the poor and his care of animals, was held up by the Catholic Church as model of piety and noble work and formally canonized in 1622. His similarly devout wife, Maria Torribia, was a faithful companion and known as a holy hermit after her husband’s death. She was beatified in 1697. Such officially recognized peasant couples are rare in the realms of Catholic devotion, indeed Isidore and Maria may be the sum total. Not surprisingly, they are known as the patrons of farmers and laborers. In the predominantly Catholic agricultural community where I now live, the old local papers lying around the farmhouse record an active Society of St. Isidore chapter that goes back years.

As the product of a Catholic/Protestant marriage who rather early left the Roman way and now would best be labeled an evangelical Anglican, I try to properly appreciate the communion of saints despite being turned off by the excesses associated with the cults of the saints. As for Isidore and Maria, some traditions have the couple permanently abstaining from sexual relations, even living apart, after the death of their only son. At first blush, this strikes me as the sort of story driven more by an ascetic agenda than a fidelity to actual history. A lengthy 19th century Spanish source makes no mention of such abstinence and separation but instead has Isidore dying surrounded by his wife and family.

And though I believe in miracles, I don’t know what to make of the accounts of droughts being broken in response to the parading of Isidore’s corpse or Maria’s severed head. These are the things that can drive some Protestants to completely ignore the examples of faithfulness highlighted by the Vatican, but I really am not looking to start a skirmish over the idea of sainthood.

Instead, I think Isidore and Maria—faithful tillers of the soil—offer acres of potential common ground. As the same National Catholic Rural Life Conference that mailed the poster to my great-grandmother 70 years ago now says on its website: “The virtues found in the lives of Isidore and Maria—commitment to family, love for the land, service to the poor and a deep spirituality—are qualities that still can be found in rural America.” That seems like excuse enough for a feast among those of us who, regardless of our religious backgrounds, want to see that sentiment remain true. So raise a glass of local brew and put some grass-fed beef and home grown veggies on the grill, it’s time to celebrate St. Isi’s Day!

John Murdock is currently working on a book about Christian creation stewardship. He regularly writes at First Things and blogs at republicantreehugger.blogspot.com.

Great start! Keep writing here…

I enjoyed reading about a new found treasure at our great-grandmother’s house. Thanks for sharing!

Comments are closed.