Leonard Cohen occupies an unusual position in popular music history. He is routinely neglected by those “Best of the 60’s” nostalgia-fests you see on VH1, CNN, or PBS, yet when he emerges from seclusion once or twice a decade, he lights up the critical landscape like a comet blazing across the sky. You can just about picture the tastemakers slapping their foreheads, saying, “Oh yeah, Leonard Cohen! One of the greats. How did I forget him?”

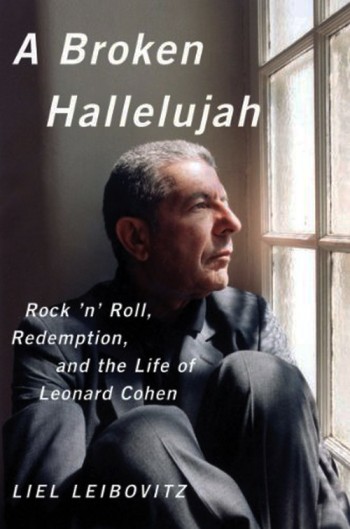

To be sure, Cohen’s profile has risen in recent times, due in part to the proliferation of cover versions of his song “Hallelujah”—which seems to have become a sort of go-to anthem for millennials struggling to express their incohate religious longings—on shows shows like The Voice and American Idol, but in the main he remains a songwriter’s songwriter. There are a number of probable reasons for this, first and foremost Cohen’s sepulchral voice; one could make the argument that it is actually a richer instrument than that of his chief rival, Bob Dylan, but his dour intonations coupled with equally dour subject matter tend to make his work a harder sell. Then there is the fact that, in terms of both content and style, Cohen has remained stubbornly out of step with the prevailing culture of his times. Dylan, too, has stood aloof from fads and politics since at least 1966, but prior to that he was considered the “spokesman of his generation” due to his uncanny ability to channel the zeitgeist. Cohen was never a spokesman for anything, apart from a certain strain of doomed romanticism. One of the many highlights of Liel Leibovitz’s fascinating new book A Broken Hallelujah: Rock ‘n’ Roll, Redemption, and the Life of Leonard Cohen is the assertion that Cohen never quite “clicked” with an audience until he performed for a group of psychiatric patients at England’s Henderson Hospital in 1970. This was Cohen’s “Folsom Prison” moment. As he explained: “The experience of a lot of people in mental hospitals would especially qualify them to be a receptive audience for my work.”

Leibovitz’s book makes clear that there have only been sporadic moments of true connection between Leonard Cohen and his audience. After the Henderson performance there was a series of impromptu gigs for Israeli soldiers on the front lines of the Yom Kippur War (Cohen had impulsively flown to Israel at the start of that conflict and was spotted in a cafe by some soldiers who whisked him off to entertain the troops) and finally there was Cohen’s triumphant 2008 “comeback” tour, which only came about because his longtime manager stole most of his money and he needed to do something to recoup the loss. For much of the rest of his career, the musician and erstwhile novelist has drifted along in pursuit of an inscrutable muse, in the thrall of an idiosyncratic religious ecstasy. He attracts us not because of his empathy but because of his otherness.

Leibovitz states at the outset that his book is “not a biography” of Leonard Cohen, at least not in the traditional sense, and he’s not kidding. We learn almost nothing about the women who inspired Cohen’s most timeless songs—Marrianne and Suzanne are mentioned only in passing—and little explanation is given as to why and how the young and seemingly impoverished poet ended up on the Greek island of Hydra, writing full time with no apparent need of a day job (my online research reveals this to have been achieved with the help of an inheritance). Instead, Leibovitz sets his lofty sights on mapping the evolution of a soul. In this endeavor, he mostly succeeds. He correctly situates Cohen within the mystical, kabbalistic tradition of Judaism, and writes perceptively of the young artist’s struggles against the heavily secularized Judaism of his Montreal upbringing. Leibovitz commands what appears to be an encyclopedic knowledge of Jewish thought—both ancient and modern—and his unpacking of this knowledge in the service of Cohen’s spiritual evolution is deeply illuminating. In Leibovitz’s telling, Cohen’s vocation is essentially a religious one—an assertion that will no doubt surprise some of Cohen’s more casual listeners. But Leibovitz makes a compelling case for the fundamentally religious nature of Cohen’s work. “[Cohen] is attuned to the divine,” he writes, “whatever the divine might be, not with the thinker’s complications or the zealot’s obstructions, but with the unburdened heart of a believer.” Some may find this religious aspect difficult to square with Cohen’s other noted preoccupation (sex). But Cohen himself explains this rather succinctly: Taking The Song of Songs as his model, he says, “Real spirituality has its feet in the mud and its heart in heaven.”

Leibovitz does sometimes get carried away. Of Cohen’s novel Beautiful Losers, he writes, “Cohen wasn’t juxtaposing nipples and saints for literary effect, as he’d done earlier in his career. He was doing it because he now knew that both were essential components of the world, both vessels of pure emotion, deserving of close study and devotion.” Compare this sentence with Cohen’s explanation of the same idea above. The former is grounded and commonsensical, the latter is vapid and unintentionally humorous, like something Will Farrell might intone during a Saturday Night Live spoof on bad academic writing.

Fortunately, Leibovitz is, by and large, a very capable writer. The book’s chief fault is that it feels padded in its second half. Promotional materials for A Broken Hallelujah trumpet the fact that its author was “granted access to Cohen’s private papers,” but those papers seem to have pertained exclusively to Cohen’s early career as a poet and novelist. Once Cohen journeys to New York to begin his music career in the mid-1960s, the door closes on our voyeuristic access to the contents of his psyche.

In that first half of the book, however, we are treated to an intimate view of a young writer’s ambitions and struggles—of his desire not just to find his own voice, but to play a part in the establishment of a uniquely Canadian literary voice free of any envy toward its southern neighbor. “What it boils down to is that we’re afraid of making fools of ourselves politically and artistically,” Cohen told Canadian journalists in 1964.

That’s exactly what we must do … produce with the courage to fail, and shed this phony sophistry, this dream of urbanity that isn’t ours. In this country, we’re scared of being labeled hicks, yet no one cares: They don’t care in London, they don’t care in New York. I don’t go along with the sophisticated attitude that ridicules all talk of a new Canadian flag and the rest of the Canadiana that we’re immersed in each and every day. Unless we explore our own possibilities—these things we consider corny—then we will lose something valuable.

It is somewhat disappointing, given the fervor of this statement, that Cohen largely abandoned his regional preoccupations when he took up songwriting. Canada remained a part of his artistic consciousness, but it never again resided in the forefront as it had during his literary career. Perhaps this was inevitable: Canadian literary critics had delivered a mixed appraisal of this work, and he may have wondered why he continued to bother. Perhaps, too, his understanding of the Canadian soul evolved. He later said, in apparent contradiction of his sentiments above, that, “We are free from the blood myth, the soil myth, so we could start over somewhere else. We could purchase a set of uninhabited islands in the Caribbean. Or we could disperse throughout the cosmos and establish a mental Canada in which we communicate through fax machines.” That seems a clever and playful statement until you re-read it and realize that it doesn’t mean a damn thing. Maybe his loyalties shifted to Israel, a country that appreciated and celebrated his work without reservation. At any rate, Leibovitz doesn’t have much to say on Cohen’s shift away from the regional, which strikes me as a missed opportunity.

The second half of the book meanders interestingly, albeit unevenly, through Cohen’s music career, wandering off on long, almost entirely irrelevant tangents exploring the artistry of the Beatles, the Doors, Emerson Lake and Palmer, and other contemporaries of the ’60s and ’70s. Leibovitz’s incisive analysis of Bob Dylan is perhaps the only side road that has any bearing to the subject at hand, as Dylan and Cohen can be seen as almost perfect counter-balances to one another. The former’s work is verbose, freewheeling, ragged, spontaneous, and passionate, the latter’s restrained, polished, studied, and understated. Both are Jewish songwriters preoccupied with the Bible. They’re almost two sides of the same coin, and Leibovitz explicates this dynamic perfectly.

Leibovitz’s lack of interest in exterior events can make for some odd moments in the narrative. Dramatic episodes in Cohen’s life, when covered at all, come off strangely flat due to lack of context. For example, we learn late in the book that Kelley Lynch, Cohen’s “onetime lover” and longtime manager, made off with most of Cohen’s lifetime savings while the singer was sequestered at Mt. Baldy Zen Monastery in 1990s. This is just about the first we hear of Ms. Lynch, and it’s unfathomable to me how any writer—even the author of an “intellectual biography”—would fail to lay the groundwork for this pivotal event, neglecting to sketch the contours of Lynch’s and Cohen’s earlier relationship so that this moment of betrayal might carry some weight. Instead, Leibovitz just breezes through it, not really adjusting his volume or tone, seemingly impatient to get to Cohen’s triumphant comeback tour.

That visit to the Buddhist monastery is yet another missed opportunity. After the collapse of his engagement to the actress Rebecca De Mornay, Cohen took refuge at Mount Baldy for five years. Two years into that stay, he was formally ordained a monk in the Rinzai school and was given the name Jikan, meaning, appropriately, “silence.” People tend to make a big deal out of the fact that the Beatles went to India for three months, but Leonard Cohen retreated to his mountaintop for five years, spending much of that time in silent meditation. That would be a radical change for anyone, let alone a celebrity accustomed to public attention, yet the experience only merits a few paragraphs in A Broken Hallelujah. What’s more, Cohen’s eventual return to public life is treated as a sort of failure or abdication of his monastic ambitions. That strikes me as a decidedly Western, non-Buddhist way of viewing the situation. A Buddhist might say that he remained at the monastery for the time period that was appropriate for him, and left when it was appropriate for him to do so. Cohen himself has credited the experience with helping lift his lifelong depression, which sounds like an unqualified success to me.

Still, Leibovitz can hardly be faulted for not being as conversant in Buddhism as he is in Judaism. In the overall arc of Cohen’s life and work, the former is subservient to the latter. Yet, given the importance of Buddhist practice in Cohen’s later life, and the fact that this book focuses on his inner development, the subject certainly merits more space than it is given.

Leibovitz’s greatest contribution to the emerging field of “Cohen Studies” is his exploration of the concept of duende. Traditionally, this term has been used to describe a specific musical technique: “a stammer, a wavering emission of the voice,” in the words of Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. But Leibovitz, paraphrasing Goethe, expands the definition to encompass “that profound and nebulous sadness we all feel but can’t easily articulate.” It haunts the edges of most of our great art. Tom Petty has recently pointed out that George Harrison’s song “Here Comes the Sun” derives much of its power from a single line: “It’s been a long cold lonely winter.” This allusion to a dark period in the recent past lends added significance to the sun’s appearance. That’s the duende at work, and Cohen’s songs are full of it. Sometimes, as in Harrison’s song, it appears as a minor shading. In other cases, it is the primary component, the melancholy epiphany. Utilized properly, the duende effects a catharsis for the listener. Leonard Cohen is a master at that: he is the type of writer who can make sadness feel good, hence his success at creating an uplifting experience out of the performance of a bunch of suicidal laments to a room full of psychiatric patients. He has done this from the very beginning—first as poet, then as an author of fiction, and finally as a songwriter. He is one of the greats, even if his understated nature often relegates him to the shadows. And, despite its many oversights and limitations, I am grateful for Liel Leibovitz’s thoughtful attempt to divine the motivations of this thoroughly original soul. A Broken Hallelujah, in its best moments, represents a new approach to the art of biography.

Robert Dean Lurie is a writer and musician based in Tempe, Arizona. Raised in Minneapolis, MN, he spent subsequent years in Seattle, WA and Athens, GA. Thus he can lay claim to having stood on the sidelines of three of the most happening music scenes of the last 40 years. Now he wanders the desert. He is the author of “No Certainty Attached: Steve Kilbey and The Church” (Verse Chorus Press, 2009) and co-author (with Ray Fisher) of “The Edge: Life Lessons From a Martial Arts Master” (CreateSpace, 2013). His essays on arts and culture have appeared in National Review, Blurt Magazine, The American Conservative, Crux Literary Journal, Bootleg, and Chronicles.

I’m with Lenny… Everybody Knows (what we must do)… First we take Manhattan…

“Let’s sing another song, boys! This one has grown old and bit-ter.”

Quite helpful analysis of a complex and enigmatic figure. “Broken Hallelujah” sounds like a worthy read.

Comments are closed.