I am ambivalent about Thanksgiving. Giving thanks is not a problem though I am sure I could show more gratitude especially when stuck behind some driver in the passing lane who doesn’t know how highways work. I am one of those Protestants who still prays before meals (and who considers crossing himself so that fellow diners don’t think this guy with his head bowed is looking at his smart phone). I am even one of those Protestants who considers the Christian life, as the Heidelberg Catechism puts it (are Peters and Polet getting nostalgic?), to be one where gratitude characterizes “the whole of our conduct.”

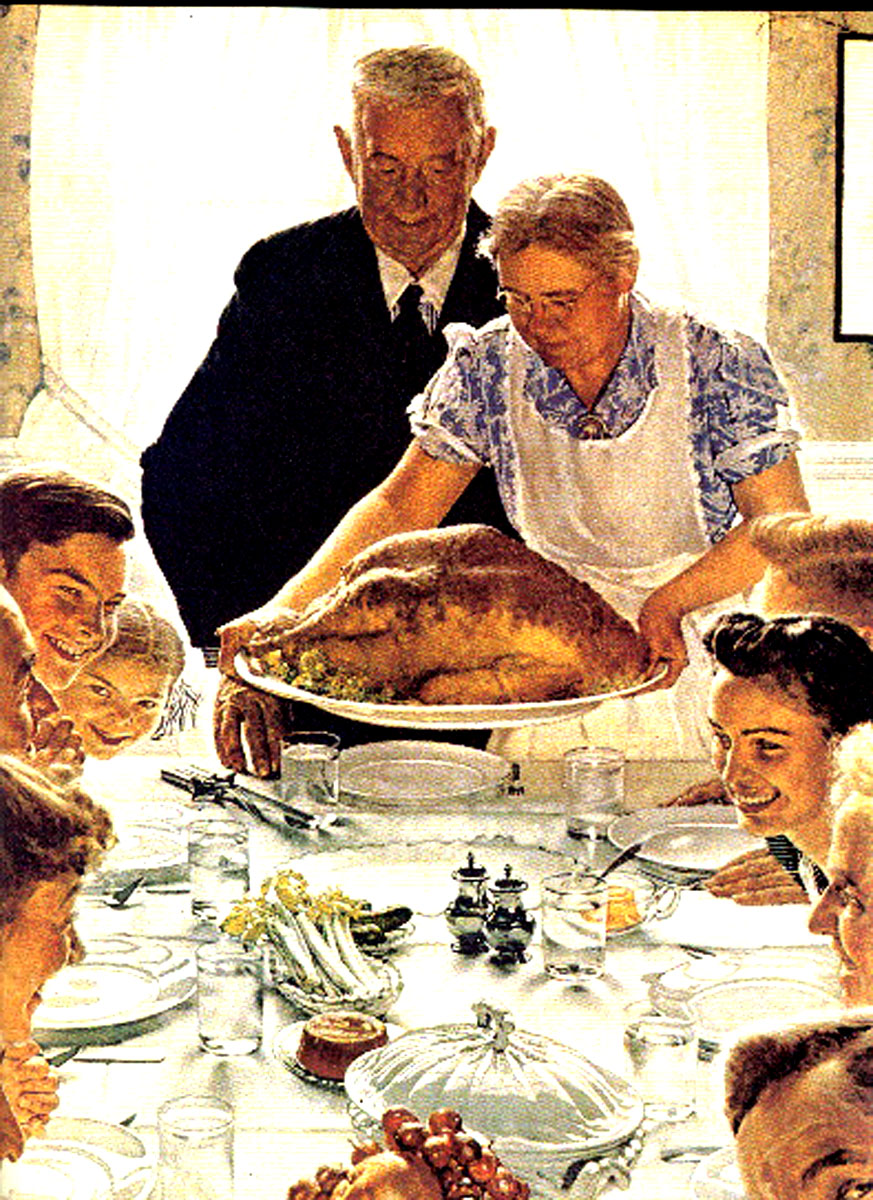

I am also an American who considers the Thanksgiving Holiday the best feast day of the year. It is an excuse to overindulge on carbs, enjoy a four-day weekend, and not have to buy or wrap gifts. And if you are the head chef in the home, the meal is one of the most challenging if only because it requires a degree of organization and timing that no other menu does. How do you get nine different hot dishes to the table still hot? And if you’re the one who sets the table, how do you find room for those nine dishes?

But how does a nation express gratitude? How do citizens ritualize it? To whom do Americans express thanks?

Thanksgiving has religious origins that give even conservative Protestants pause if only because the English Protestants who more or less launched the holiday taught a covenant theology that imagined God to have a special relationship with England that resembled the one the Israelites enjoyed in the Old Testament. (This English Protestant background also accounts for Canadian Thanksgiving.) Further reason for Protestant ambivalence is that pesky problem of how the English colonists treated native Americans. Thanksgiving may be a way to commemorate a time when European and native American shared a meal, but that memory only brings up other more troubling ones.

But when it comes to Thanksgiving as a national holiday the logic is no more compelling. In 1789 George Washington employed a day of thanks to bolster support for the Constitution. In 1863 Abraham Lincoln standardized the day and stamped it with Civil War associations, a time to thank God for blessings and to express “humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience.” By 1939, government and war were distant memories compared to the economy which prompted FDR to move Thanksgiving up a week so that shoppers would have more time to spend on Christmas.

Now Thanksgiving becomes something of a presidential hot potato. For Bush the day was still one upon which to thank God for his blessings, though how Americans who didn’t believe in God were supposed to spend the day was not clear. For Obama, Thanksgiving has become a time to thank God and each other for Americans’ many blessings.

Of course, getting a day off and roasting a turkey is hardly oppressive compared to the way that millions of humans have suffered for their convictions. One of the movies that my wife and I like to watch on Thanksgiving is Barry Levinson’s “Avalon,” a film about three generations of Jewish Americans in Baltimore who used Thanksgiving to gather and tell family stories about coming to America. It is a remarkably sad movie because it shows not the decline of Thanksgiving but the unraveling of a family as entertainment, consumption, and careers cut the thick ties that immigrants built to navigate their way in a strange land. Thanksgiving, a foreign holiday and menu for Jewish Americans, was not a burden. It was and remains a holiday that Americans can fill with meaning as freely as they decide whether to stuff the turkey or make dressing.

As a Front Porcher, the plasticity of Thanksgiving may actually be a plus. Let families, houses of worship or President Obama’s community centers create their Thanksgiving moments as they wish. A standardized national day of memory and meaning is neither localist nor a ritual our fragmented society can well observe. Even so, the Protestant in me wonders if Thanksgiving is worth having if its meaning varies to the point of being meaningless.

[…] by Roman Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, and agnostics). Over at Front Porch Republic I develop this […]

[…] I enjoy a break from responsibilities and look forward to a festive meal and time with friends, I enter yet another holiday with great ambivalence. With classes behind and grades in, Christmas is indeed one of the most […]

Comments are closed.