Rock Island, IL

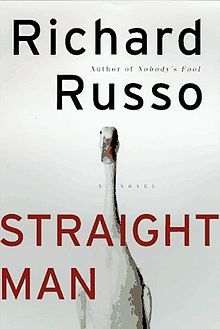

When Straight Man came out in 1997 there was some talk, at least in my circles, that one of its main plot devices—Professor Hank Devereaux’s threat to kill a goose a day until he gets a budget from the administration of his second-rate university—was a bit of a stretch, that Richard Russo, later the winner of a Pulitzer Prize, had gone too far, that he’d asked too much of his readers in the way of credulity. No chairman of any academic department would do such a thing, not even the chairman of an English department. This campus novel, this academic send-up, had descended into farce.

But the truth is that it hadn’t. And not only wasn’t it a farce; it might not even have been a send-up.

That same year I heard about a tenured senior professor who, having learned that a family of raccoons had moved into a campus construction project—the one in which this particular professor was going to enjoy new digs—brought a shotgun with him to campus one day and discharged it: that is, he fired a gun not only within the city limits; he fired it on campus. Forget what the law says about this. If you shoot a raccoon on a college campus, some sociologist somewhere is going to be offended on behalf of all raccoons everywhere, and the moral outrage will be impressive.

I once heard about a dull tenured professor who stood up to leave the lunch table at which he had been holding forth. Several of his colleagues, not otherwise given to prayer, had been praying to die over their chicken kiev. This professor’s pants, not having received the memo concerning his departure, failed to stand up with him. Fortunately for him his interlocutors had been rendered comatose by his soporific conversation and hardly noticed. And because his pants were not directly employed in the unending task of self-congratulation, I’m not altogether sure he noticed either, though a food-service worker survived to tell about it.

I myself was once asked to review a book for a student newspaper. The woman who wrote the book that I was asked to review had, in writing it, found herself incapable of parroting oft-voiced and uncritically accepted academic orthodoxies. I reviewed the book favorably, whereupon—and this was during my probationary years—a whole meeting was called to discuss what was to be done about me. The faculty members invited to this meeting were … how to put this … only of the non-urinal-using kind—unless there are physiological tricks and restroom acrobatics of which I am unaware.

My point is that there probably isn’t anything so outrageous that it doesn’t belong in a campus novel, and this includes the threat to kill a goose a day until the chairman of the English department gets his budget. When the novel opens Hank has a swollen nose. It has been punctured by the wire of a spiral notebook that a female colleague has bludgeoned him with during a committee meeting. If you think this plot device is an abridgement too far, remind me some day to tell you about the time a woman punched me in a graduate seminar.

I waited until the paperback version of Straight Man came out before I bought and read the book, and then I read it quickly, fearing that, laughing too hard, I might die falling out of my chair or off my couch and then, being dead, be deprived of the pleasure of finishing the book.

Soon after that I loaned my copy to someone, I forget to whom, and never saw it again. Thus is goodness ever repaid. But then about six years ago I was at a library sale one Saturday, waiting for my kids to get their week’s supply of books, and I spotted a copy of Straight Man. It had been checked out fourteen times in seven years and not once in the ensuing three, which means it merited discarding. (Libraries are no longer repositories of books; they are “information retrieval centers.”) I parted with my dollar, took a clean and unmarked first edition home, and spent the weekend re-reading this hilarious novel. And this time I gave myself wide berth: the queen bed I read it on would contain me and my laughter and forestall yet again any death-by-mirth.

I have read, with pleasure, all but two of Russo’s books. (The remainders, both among his earlier efforts, are in the queue.) One, Empire Falls, routinely makes it onto the syllabus for my seminar on the Catholic novel. I have an astute colleague who likes Russo’s work but who calls him a “baggy” writer, and I find myself obliged to concede the point. But when the dialogue and the jokes are good, when the narrative pace is leisurely and the style uninhibited, as in Russo they are, I’m as patient a reader as you’ll find. Baggy? Be as baggy as you want, Rick. I’m in for the long haul. Promise. Just show me my foibles and make me laugh. (Also show me what shit-heads other people are.)

And so when that hiatus in the academic calendar came around again this year—I mean the one during which we give lip service to gratitude but are, on the whole, insufficiently grateful—I picked up Straight Man and with insufficient gratitude read it for a third time.

Few novels survive three readings. For me Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory has never slipped a notch, not even after more than a dozen readings, and that’s saying something. Nor has Waugh’s much-maligned masterpiece, Brideshead Revisited, moved so much as half an inch south. (Critics who adore champagne complain of Brideshead’s “champagne prose”—and they do so in prose so dull and abysmal a man might beg for death by Dickens and diet Coke. These dullards should be condemned to swill Busch beer in hotel rooms under prints of the Laughing Cavalier, reading books that parrot the permitted sentiments they nod in agreement with before nodding off into the sleep of intellectual death.)

If I confess Straight Man slid a little the third time through, its bagginess emerging just a tad, I must also insist I’m no more done re-reading this book than I’m done re-reading the other books in the lineage to which this one belongs, among them Lucky Jim, The Lecturer’s Tale, Eating People is Wrong, Changing Places, Staggerford, Small World—the list is long and the books delightful, Straight Man somewhere near the top of the list, and not because it’s deep but because it’s funny. And funny isn’t easy, as John Mortimer—another funny writer—once said. (He said it of Muriel Spark, who was wickedly funny—and apparently a bit wicked as well.)

By the time Russo got around to writing Straight Man he had written enough fiction to know that this novel couldn’t be about academics only, and so he gave us Mr. Purty, the local landlord who is as prone to malapropisms as English professors are to inelegant expression. He also gave us Missy Blaylock, the local TV reporter, who opines that her breasts, buoyant in Tony Coniglia’s hot tub, are too good for the local market, just as every academic in Russo’s second-rate university is too good to be an academic in a second-rate university.* (Tony Coniglia is a biologist given to fornication and metaphysical speculation, and Missy Blaylock’s two best features conduce to one of professor Coniglia’s two chief interests.) And then there’s Hank’s daughter, who isn’t bookish at all, and there’s her clumsy adulterous husband, who needs a talking-to—and who gets one.

Hank’s wife is one of the best phantom presences you’ll hardly ever see.

And there’s Hank’s father, the academic superstar, who as a husband and a father—who, indeed, as a human being—is a complete failure, because not unlike a lot of academics he fails to understand that hypermobility is lethal, that prestige is chimerical, that tumescence is fleeting, and that life isn’t lived between the covers of books.

I assume that some readers have read this book and some have not, and I’m attempting here to appeal to both: read it if you haven’t; re-read it if you have. Its author seems to think that over a lifetime we’re maybe capable of slight moral improvement—if we’re lucky or attentive—but that we’d all be better off if only we were capable of laughing at ourselves and at those around us and, perhaps above all, at the vanity of human wishes—assuming we can recognize the vanity of human wishes.

In an interview conducted for Empire Falls Russo called Straight Man “a lark.” He meant that to some extent the book wrote itself, that it came more easily to him than did his preceding books and the one immediately following. Straight Man was, as it were, given to him. My own view is that it isn’t his best book, though it is probably his funniest—and they’re all funny in one way or another. What he’s doing throughout is looking at a situation in which tempers are high because the stakes are so low. The situation he’s looking at happens to be called Higher Education, but it might also be called The Human Predicament. We all think more of what we might think less of. The final scene of the novel suggests that academics are especially stupid (which, in my view, they are). But that, I take it, is but another well-deployed plot device—like Hank’s phantom kidney stone, which provides a fair number of the novel’s yucks. If there were something worth fighting for in Higher Education, we might see a serious treatment of it. At Hank’s university there isn’t any such thing worth fighting for, unless it’s Hank’s secretary, who’s a better writer than the faculty members she works for—and also a better person.

That is to say: what’s worth fighting for takes place outside the university. It takes place outside the alleged real world and inside the real real world.

Not that a serious treatment of the academy isn’t out there. I can think of one fine—one really fine—example. I expect that many of us Under The Big Top would love it if the three-ring acts we’re involved in were in fact real and worth caring about. Until such a time as they are, we do well to buy a bag of popcorn and laugh at the circus show.

_________

* “We have believed, all of us, like Scuffy the Tugboat, that we were made for better things. If anyone had told us twenty years ago that we would spend our academic careers at West Central Pennsylvania University in Railton, we’d have laughed” (132).

“(Libraries are no longer repositories of books; they are “information retrieval centers.”)”

I rarely read fiction, not even the newspapers, but I frequently take advantage of libraries that have discarded their proper role in society. Their discards end up being sold at reasonable prices by Amazon booksellers, and end up on my own bookshelf.

Straight Man is my favorite book, and your post precisely captured why it’s a keeper. Thanks for reminding me to reread it (I also “loaned and lost”).

“Baggy” sounds like surplus or outsized verbiage. That’s the opposite of Russo’s writing. I’d call it lean or taut or understated.

Just yesterday one of Russo’s ‘taut’ lines popped into my mind. I was stuck in a jury room with 11 constantly-talking extroverts. Russo: “These men did not possess library voices.”

(Might not be exact quote; I think it’s from Risk Pool.)

This is one of my favorite books. I first heard about this book on the road trip for Dr. Nolan’s memorial. I picked up a copy that weekend and read it. All I could hear was your voice. Recently, I “re-read” it via an Audible subscription. Even with an actual voice reading it to me, I still only heard you. I mean that as a high compliment.

I pursue a similar strategy to that of John Gorentz: I tell our library what books I want them to buy with my portion of the available funds for the year, knowing that they’ll just stick them on the “free” cart in a few years, at which point I can keep them and loan them out to my students. Long way around, but that’s what you get with the information retrieval center….

Comments are closed.