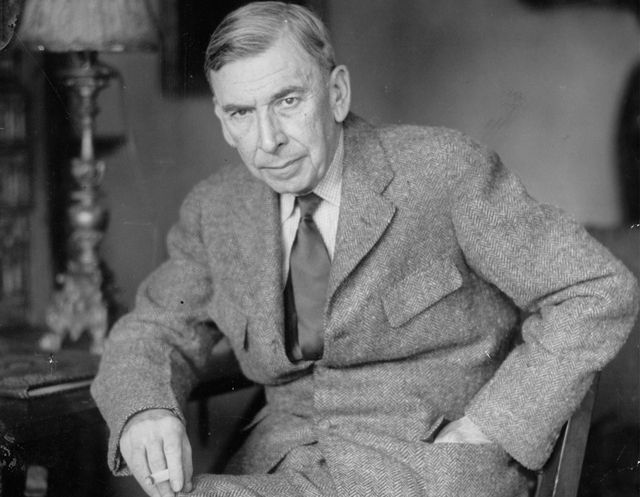

In this excerpt from America Moved: Booth Tarkington’s Memoirs of Time and Place, 1869–1928, Tarkington reflects on the changes he observed in America following the end of the Great War.

Not many of the soldiers who came back to the welcome at home returned wholly unchanged; but the prevalent change, after a first restlessness had passed, seemed clearly defined in a sharp and sturdy patriotism: what they have fought for men will not meekly allow to be tampered with, and as the Grand Army of the Republic and the Loyal Legion became the oaken heart of the nation’s patriotism after the Civil War, so does this newer Legion become that after the Great War. But in numbers of the young men who had fought there were other changes; and for some of them the shock to their lives had shaken all the old fundamentals they had formerly accepted: they questioned everything and especially they questioned whatever seemed to them dogmatic. They questioned the historic conclusions upon which they had been brought up — particularly historic ironclad conclusions that certain things were right and certain other things were wrong and in this questioning and challenging they were not alone. All youth, everywhere, had begun to question and challenge; and many new prophets offered plausibly to lead them against the old.

This was a disturbed and questioning world, indeed, at the end of the Great War; it was like the sea covered with heaving wreckage and seething after the hurricane; fierce winds blew sporadically where the heaviest storm had passed and there were gulfs still in wild turmoil. After the Russian Revolution had made that enormous country a republic, the comparatively small but perfectly organic Bolshevik party had adroitly and violently disposed of the revolutionary leaders and had restored Absolutism with Lenin and themselves in place of the Czar. Their method of “appeal to the people” was essentially the immemorial appeal of any political party platform, or, for that matter, of any dictator’s pronunciamento: “We’re doing this all for you.” And the Bolsheviks did promptly “pass a farmers’ relief bill,” vastly increasing the number of property owners in “communist Russia.” Naturally, everywhere else, the poorest people, and those who were out of work or who had a hard time to make both ends meet on low wages, the troubled and discontented all over the world felt a great deal of sympathetic excitement.

In the defeated countries this excitement became a contagion; there were riots that became temporary revolutions, and even in America there was uneasiness; many substantial citizens were disquieted, not trusting the intelligence of the “masses.” Agitators, orators, and pamphleteers did what they could to bring the populace to more or less radical socialist ways of thinking, and for a time they seemed to be having a rather dangerous amount of success. Most of them were foreign born or of foreign parentage; they were theorists who had contracted abroad the habit of being resentfully “against the government,” or they had inherited that habit from their parents; and in some instances the habit had become actually a profession, the practitioners of which had no other means of livelihood. But almost every one of them was passionately sincere in the pathetic belief that his own socialistic prescription was the universally healing medicine for ailing humanity — even if the greater part of humanity had to die of the remedy.

They made converts, especially among the young of that disquieted and questioning time. For it is true that if a person is a socialist at twenty his heart is right and that if he is one at forty his head is wrong, even though his heart may still be right. The academic kind of socialism, of course, is but a laudable Christian sentiment for universal brotherhood; it cannot be translated into a working system, however, until men universally are governed from within themselves by brotherly feeling; it is a feeling that cannot be imposed from without, either by legislation or revolution. Moreover, “state ownership,” in this country particularly, proves to be in reality control by politicians, “smothering bureaucracy,” not economical, and a loss of that individual liberty congenial to “the land of the free.” The socialist’s attack upon the “capitalistic system” is often only a generous and confused mind’s indignation with nature itself for not making mankind angelic at the outset; though sometimes it hints of an origin in what lately our youth are so fond of calling the “biological” — an ancient urge still surviving many ages after bees and ants branched off as communists; something still appears to survive in man, sporadically exciting the wish to become only a cell in a single organism of uniform cells. The urge is impotent; socialism is communistic at its base, and communism as a reality actually attempted is the most mocking of all delusions, being merely a change in the names used to designate bosses. It does not really matter whether the man in the limousine is called “millionaire” or “commissar” if he has the same actual power under either title, and he necessarily has unless there is chaos. The Russian collapse, before it was realized that the word “capitalistic” really meant “human,” approached chaos for a time and produced one small but reasonable party — the extreme leftward feather of the left wing, the party of chaos or Perpetual Revolution. Lenin recognized it when he told the “very poorest” to attack those who were somewhat less poor and seize their goods. After that, of course, there would again be some who were the “very poorest,” and they in turn must attack and seize. Never could there be equilibrium, and the nearest approach to actual communism must be reached only by incessant revolts. And as the revolts would have to continue until everybody was killed, this party did indeed offer a consistent, logical programme; they were the only thoroughgoing realists among the whole body of communists.

Many of our American young people and others who were older in years, having been agitated and troubled in thought by the war, caught at socialistic straws for the world’s salvation and turned hopeful faces toward Russia. Socialism, usually of a benevolent, rather vague kind, began to be a vehemence among groups not too humble minded to resist being defined as “young intellectuals”—a type as well as a definition seeming to spring in this country from that time. Not a few of them had their own idea (seldom derived from the dictionary and frequently not from Karl Marx) of what socialism meant, though they were nearly all familiar with such phrases as “everything for use and nothing for profit”; and they enjoyed a pleasant kind of superiority not unnatural to youth. Particularly this superiority is congenial to youthful socialism, which from a height characteristically pities the stupid and uncomprehending world far below. The complexities of life seem simple to the kind of thinking that perceives no great difficulty in the way of altering instinct by statute; it is, however, somewhat disturbing to imagine the size and necessary wisdom of a bureaucracy capable of putting into practice by force an ideal thus expressed: “From everyone as much work as, by the decision of a government official, he ought to do; and to everyone whatever the government official decides that everyone needs.” And yet to those who believe that it is possible to eliminate nature by legislation no insurmountable obstacles appear to stand in the way of “from everyone according to his strength; to everyone according to his need.” For this is the angelic will-o’-the-wisp they follow and offer to capture and fix as the desk light of millions of government clerks. Nevertheless, the youthful socialism that followed the war was born of sympathy for the under dog and of the effort to think how redemption could be brought to a troubled world; and as an emotion it was genuine and generous.

As thought, it was a symptom of change; it was a part of the new questioning, the new doubts of the value of all established things. The characteristic questionings of every new generation as it begins to think a little for itself were not quietly simmering as aforetime. The minds of this generation of young people had been startled and shocked by the most colossal and terrific war the world had known. No wonder they began to question the old order since, so far as they could see, it appeared to bear the responsibility for all that madness of destruction.

*****

As our army disbanded and the tensity of the country relaxed, there seemed to be a period of uneasy anticlimax; the saloon was gone; Prohibition had come with the war; “equal suffrage” was certain, and presently women would vote; there was a pause during which men seemed to be asking in tired voices, yet anxiously, “Well — what now?” Then, slowly at first and after a trying depression, business attempted to be “resumed as usual”; the young soldiers, not often easily or with great immediate satisfaction to themselves, began to get back into their former occupations, or to find new ones, or to continue interrupted educations. Most of them suffered from restlessness; changed themselves, they came back into a changed world that was still confusedly changing.

Moreover, during service under arms military discipline had taken the place of the former accepted guides to conduct, and as on furlough “all rules were off” for the gayer or wilder spirits, so, when military discipline was permanently removed, those former rules it had supplanted were not immediately resumed in all their pristine force. That force, indeed, was shaken by doubts, not only in the minds of many of the returned young soldiers, but in those of the girls who had been kind to them when they went away to war and now welcomed them home. For girls were changed, too; thousands of them had crossed the dangerous seas and made themselves part of the war; other thousands had prepared themselves to follow; and all the rest had done “war work” of one kind or another. Some of the work girls had done was rough as well as perilous; some of it was heartbreaking; some of it was shocking. “Feminine delicacy” and chaperonage had become almost extinct ideas—temporarily almost extinct at least—and when revived later they were found to be greatly enfeebled.

That uneasy pause of depression and confused readjusting was a long one; it lasted longer than the time we had spent in war; but finally it began to pass, and the country entered upon a period that was like what the old spectacular drama programmes loved to call the “Grand Transformation Scene.” The blaze of glory, so to speak, in which this present epoch was to culminate sent forth preliminary showers of sparks.

During the war, babies had been born as usual, and, after the Peace, when ships were no longer needed for carrying soldiers and war supplies, immigration once more began to be multitudinous. In the meantime there had been no building; but all these new people needed housing, and the government having finally decided to become economical after its vast war spending, money lost its timidity. Building began again.

Once begun, it became almost overnight of a furious energy, and never before was seen such building up and tearing down. Our Midland city, after the pause in its heaving up and spreading out, now heaved and spread incredibly, as did all other strongly living cities. It began to pile itself higher and higher in the middle, and its boundaries moved like the boundaries of a rising spring flood. It overran its suburbs, leaving them compacted with the town, and then immediately reached out far beyond them. A new house would appear upon a country road; the country road would transform itself into an asphalt street with a brick drug store at the corner of a meadow; bungalows and theatrical-looking cottages would swiftly cover the open spaces of green; a farm would turn itself hastily into a suburb and then at once join solidly to the city. What was in spring a quiet lane through fields and woods was in autumn a constantly lengthening street with trolley-cars gonging and new house-owners hurriedly putting up wooden garages in their freshly sodded “side yards.”

Deeper in the city, more old houses came down, until those that were left became pathetic and ridiculous among the buzzing automobile “sales buildings” and tall apartment houses. They were begrimed, crowded, deafened with city noises, and seemed to know that the day of demolition was already set, yet they struggled to maintain some appearance of dignity as they breathed their last among the fumes of the gasoline that had doomed them. And in the sooty “back yards” of some of them there still stood, as a final irony, the reproachful spacious shapes of brick stables long since empty.

To the old citizen, passing by, these expiring mansions spoke wistfully of ancient merry times within such solid walls as the frantic new and costlier buildings could not afford. There had been music at night on these cramped and dirty lawns, under trees that were gone long ago; there had been laughter and good cheer and dancing on the other side of those dingy, carved walnut front doors; white hands had waved, long ago, from friendly windows that were gaunt and hollow windows now; sleek young horses had trotted eagerly out of the white-painted iron driveway-gates long dusty in the junk shops; and even the ghosts of the happy little dogs that had barked so gaily at the horses must now be choked in the city smoke.

With respect, the thoughts in this essay seem to have sprung like Athena entirely from the author’s head — exhibiting a range of reflexive ideas. It has no grounding in history.

Just as a starting point, if you are going to discuss socialism in America, you need to go back at least as far as the Pullman strike of 1894 and you need to discuss the Settlement movement and Eugene Debs.

Jim Wilton,

I thought it was an interesting essay as WWI was a time of great conformity even if the aftermath was a time of radicalism. But you have reminded me why I mostly like to read history – history grounded in specific things that people said or did to others, at specific times and places.

One question for the OP is why this is tagged as World War II. If it wasn’t accidental, it would be nice to know what connection he is making.

So good to see the news of the publication of America Moved! About time that material was available in print.

The book details don’t specify the source material. I presume it includes “As I See Myself” and “The World Does Move.” Any others?

John — the war in question is in fact World War I, as you suspected.

And Greg, yes, the source material for America Moved is (1) “As I Seem to Me,” which covers Tarkington’s early life (1869-1899, more or less) and was originally serialized in The Saturday Evening Post in 1941, and (2) “The World Does Move,” which mainly covers Tarkington’s experiences from 1895 to 1928 or so.

The publication details are given on the book’s Acknowledgments page, fyi, and I am happy to provide more detail if you want it. Thanks for your interest!

“With respect, the thoughts in this essay seem to have sprung like Athena entirely from the author’s head — exhibiting a range of reflexive ideas. It has no grounding in history.”

But this is a memoir. Are you saying that his memory’s bad, his interp. of the various events is bad, or both? If he lived through it, and wrote what he experienced, how can it have “no grounding in history”?

Comments are closed.