Saginaw, MI

This post is part of a series that will explore what prominent thinkers can teach us about today’s public multiversity, the modern university with its many colleges, departments, and other administrative units that play multiple functions and roles in our society.

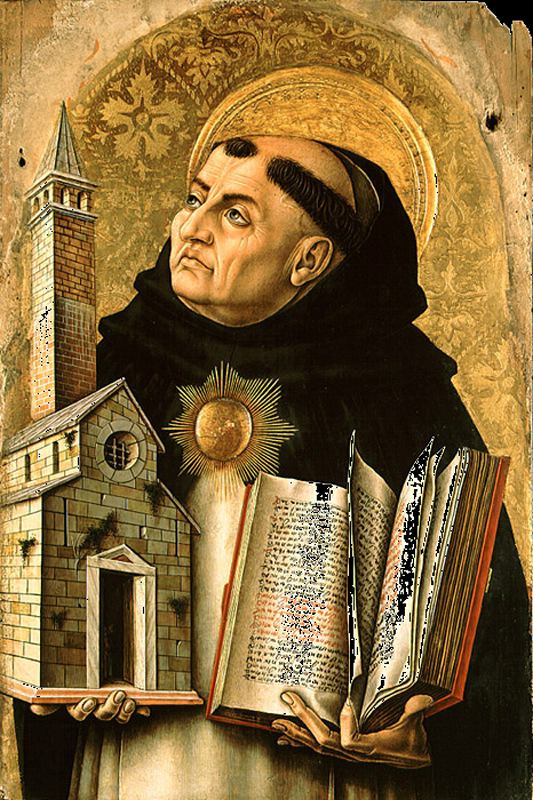

Thus far we have looked at three prominent thinkers who have offered us some ways to reform the multiversity so it can become an institution that pursues truth: Plato’s idea of periagoge, Aristotle’s concept of phronesis, and Augustine’s understanding of amare. When we reach Aquinas, we find that the medieval university has managed to preserve the classical understanding of education, or what we would call today the “liberal arts,” with its organization of the trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). But, as begun by Augustine and subsequently institutionalized throughout the Middle Ages, the liberal arts have been inserted into a new theoretical framework of reduction atrium ad theologiam: the reduction of the arts to theology. As I had mentioned in the last post, this rationale still persists today in a select few religious colleges and universities, but would be impossible for the contemporary multiversity to accept as a guiding principle or paradigm.

But if we subtract theology from Aquinas’ thought, what does he contribute to the public multiversity? Strangely, the philosophical crisis of Aquinas’ time is strikingly similar to our own in a period of increasing interconnectedness, globalization, and alleged cosmopolitanism. The rediscovery and Latin translation of Aristotle’s works during the first half of the thirteenth century ushered in a new paradigm about human life that was complete, coherent, and contrary to Christian teaching. The virtuous life of the Aristotelian philosopher owed nothing to the revelation of Christ, just as the virtuous life of Confucius, Mohammad, or Buddha owes nothing to western civilization. Are we then set on a course for a clash of civilizations, an end of history, or something entirely else? How should we navigate this new age of rising civilizations different from our own? And what place and role does the multiversity have in it?

Aquinas confronts this challenge by adapting aspects of Christian theology to Aristotelianism. Contrary to Augustine’s idea that only a single wisdom exists, Aquinas writes of two wisdoms with reason being one and divine revelation being the other: the former is aimed at the universe that did not require a later intervention of God; the latter shows us the perfection that is possible when God does. This synthesis of reason and divine revelation – or, for those given to esotericism, the tension between these two – allows Aquinas to incorporate the wisdom of Aristotle with the truth of Christ. But this synthesis is not a flawless one, as differences do remain between Christianity and Aristotelianism: the magnanimous person is not the same as the meek Christian; the object in the life of contemplation is not same as in Christian devotion.

However, by providing a place for reason, Aquinas clears a common ground for discussion between Christians and nonbelievers in the examination about the intelligibility and structure of the natural order. Although this investigation is limited in that it does not touch upon divine revelation, it does provide an avenue where truth can be pursued. At today’s multiversity, reason still rules but it can provide a space to explore divine revelation, depending upon the nature of the activity. For an academic examination of divine revelation, whether in the classroom or in scholarship, faculty should follow the rules of reason, while, for informal programs like student organizations, its members, along with its faculty advisor if so desiring, should be permitted to proselytize and practice their religiously-informed beliefs if they wish.

This arrangement in the public multiversity is not a compromise between reason and divine revelation but a synthesis of these two: the former governs the academics and the latter allows optional student practice. Students are permitted to pursue truth in both reason and faith, if they are so inclined Thus, the multiversity should permit student organizations that are religious in nature to discriminate against those who do not share their beliefs, for to compel someone to accept something they do not believe in a voluntary organization does not promote the pursuit of truth in any form. Now, of course, there are some limits to the practices and beliefs of these organizations. For instance, a student club that promotes suicide bombing should be excluded from the multiversity, in the event the NSA doesn’t get to them first. But these decisions are determined by reason, specifically by practical wisdom, and need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis from an administrator establishing the correct conditions for truth to be pursued.

The multiversity’s synthesis of reason and divine revelation therefore is different from Aquinas’, with philosophy ultimately replacing theology but still preserving a place for it. In spite of these differences, the spirit of Aquinas’ synthesis can reverberate throughout the multiversity in its search of truth among different groups of people. Unfortunately, this search sometimes manifests itself into mandatory workshops of Maoist self-criticism that aims to produce sentiments of smugness and superiority, i.e., acknowledging one’s guilt or victimhood as a badge of honor rather than trying to find a common truth for all people. But today is not the time to indulge in therapeutic self-confessionals, as we live in an age of globalization with the rise non-western civilizations as competitors and possibly foes. We need to have the multiversity find ways of cooperation rather than conflict, and Aquinas’ synthesis provides such a pathway as well as a principle for the multiversity to organize itself.

For without a principle of order, the multiversity is not capable of achieving wisdom for its students, faculty, and administrators. Unmoored, the multiversity is cast adrift into the endless sea of roles and functions without knowing why or whether it is doing them well. With the principle of synthesis, the multiversity is able to consider the fundamental human alternatives that exist and invites all to partake in a common exploration about which ones constitute truth without a priori excluding any of them, as would be the case with the medieval university. To use our reason to understand “the other” and to observe what other religious practices may teach us is the synthesis that the multiversity can possess. Aquinas’ synthesis therefore is neither a call back to an arcadia that never existed nor to project a utopia that never will but to be attentive to our present condition where reason and divine revelation both remain with us today.

Lee Trepanier is a Professor of Political Science at Saginaw Valley State University. More information about him can be found at http://svsu.academia.edu/LeeTrepanier.