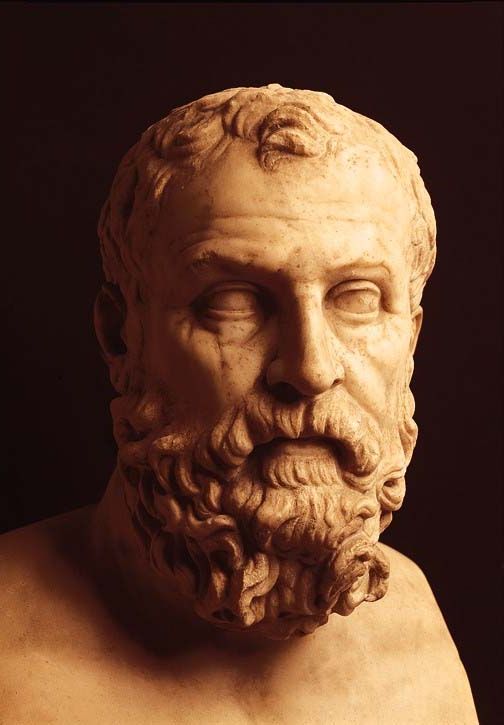

The Greeks were funny. We don’t usually think of them that way; we think of them as marbled patriarchs in togas, Really Important Men We Revere for Some Reason.

Admittedly, we don’t usually think of them at all these days; after inspiring writers, theologians and leaders for most of the last 25 centuries, they’ve almost disappeared from modern pop culture. Occasionally a television character name-drops Aristotle or Plato, demonstrating that they are the Brainy Character and can rattle off exposition. A modern schoolbook might include a tedious paragraph about a poet or philosopher, but such information is unlikely to compete with the latest video game for young people’s attention. Suggest to rap fans that they could listen to poetry, or to anguished teens that they read the Stoics, and you are likely to get nothing but horse laughter. Our cultural allergies run deep.

In fact, though, the ancients were fantastic; lusty, flirtatious, noble, self-destructive and dryly comic, witnesses to as much melodramatic intrigue as found in any fantasy epic or crime thriller today. The writing styles take some getting used to, granted, and the turgid translations often don’t help — so when I teach them to my ten-year-old, I compress the text down, Reader’s Digest-style, and we act out the characters. The other night, we read Plutarch’s biography of Solon, for example — the man most credited for inventing democracy in Athens – and acted out his defiance of the Athenian dictators.

With sticks for swords, we re-enacted the Athenians’ battle for the island of Salamis, and their humiliating defeat by the Megarians. After that, I explained, the lords of Athens created an information blackout, forbidding any Athenian from mentioning Salamis – they didn’t want to be embarrassed anymore.

“What, so everyone pretended like nothing was wrong?” my daughter said indignantly. “When everyone knew otherwise?” Yes, I said – just like today.

“Couldn’t they complain to the rulers if they didn’t like the laws?” she said. No, I told her, lords and emperors didn’t need to take responsibility for anything. They had taken a step toward democracy a generation before, I told her, when a man named Draco created their first set of laws – but they were the original draconian laws, where the penalty for everything was death. That news delighted my daughter, and soon we acted out a new scene of our impromptu play: Mr. Average Athenian litters on the street, meets Draco.

“Hey! That’s against the law!” she said as Draco. Oh, shoot, I said as the Athenian – can I pay a fine?

“No!” she said, as Draco. “The penalty is DEATH.”

That’s ridiculous! I said. “Complaining about it is DEATH,” she said.

Who hired you, buddy? I asked. “Asking who hired me is DEATH.”

As much fun as this was, the gravity of it began to sink in – Solon was ready to die. “What did he do?” my daughter asked.

He sat down and wrote an epic poem about the defeat at Salamis, I explained. He put on his hat, walked to the market, stood on a pedestal in front of everyone, and recited the entire story of the defeat. He might have even sung it, opera style.

“What happened to him?”

He persuaded a lot of Athenians that they should take back the island, I explained, and they pressured the rulers, who gave in — and Solon came up with a cunning plan to win this time. It was …

“Yes?” she asked.

I paused, not sure how to proceed. Well, I told her, you remember that part in Bugs Bunny where he dresses up like a woman, and his antagonist drops everything to come over and flirt with Bugs?

“Right?” she asked.

Well, I said, the Athenians did that.

There was a quiet pause. “You’re joking,” she said.

No, really, I said – according to Plutarch, they had their youngest, beardless soldiers dress up as girls and flirt with the Megarians, and when the Megarians jumped off their ships and ran onto the beach after them, the other Athenians leaped out with swords and yelled, “A-HA!” Or something to that effect.

After talking about the zaniness of these strategies for a while, I explained that Solon’s reputation continued to spread; he became so famous for his wisdom that he began attracting other great minds from nearby places. He became friends with Thales of Miletus, one of the first Greeks to come up with theories about how the world worked. He became friends with Aesop, who wrote the fables, and with Periander of Corinth – a group of them came to be known as the Seven Sages.

He even attracted the attention of a Scythian — Scythia included what we now call Russia, a world away in those days. The Scythian was Anacharsis, I told my daughter, who wanted to meet Solon so badly that he travelled all the way from Russia to Greece to meet him.

We acted out the scene: Solon hears a knock at the door, and opens it to find a strange foreigner greeting him. We had just seen 1938’s You Can’t Take it With You, so she acted the part of Solon as played by Jimmy Stewart, and I played Anacharsis like Russian character actor Mischa Auer.

Solon! I said in a fake Russian accent, playing Mischa Auer playing Anacharsis. I have travelled all the way from Russia to meet you! You are famous there as great thinker – I am great thinker too! We should be friends!

“You know,” my daughter said, playing Jimmy Stewart playing Solon, “around here we have a saying – if you want to make friends, you should start at home.”

Anacharsis slowly looked around. Is this your home? He asked.

“Um … yes,” Solon replied.

Then you can be friends with me! Anacharsis said exuberantly, hugging Solon.

My daughter loves acting out these stories, and since then we’ve gone through one event after another: how Solon created the rules of democracy and then tricked everyone into following them. How an ambitious dictator took over Athens by tricking its inhabitants in true screwball-comedy fashion … three times in a row. How the Athenians came up with equally zany schemes to get their democracy back.

These stories offer comedy, intrigue and swashbuckling action, of course, but they offer something else. They show us a world where democracy, science and individual liberties had never existed even as ideas, and they show how difficult they were to create. They remind us that such things are not slogans, but acts, always fragile and often courageous.

By reading these stories, which inspired emperors and saints, soldiers and scholars through the ages, we create a lifeline between our troubled culture and theirs. We see them not as statues but as human characters in the great story, at least as foolish as we, and wrestling with some of the same dilemmas. When they find a way through their troubles, we realise that there is hope for us.

Like.

Comments are closed.